| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

More Special Reports |

| Posted March 12, 2007 |

|

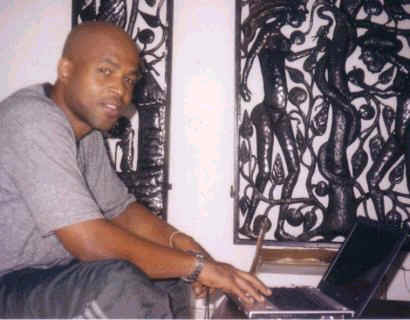

Michelle Karshan for the Boston Globe |

| Harry Desiré helped found Alternative Chance, a criminal deportee advocacy organization, after he was deported to Haiti. Desiré spent five years in New York State prisons. |

| Influx of deportees stirs anger in Haiti |

By Amy Bracken, Globe Correspondent |

| Some believe U.S. policy helped boost crime rate. |

PORT-AU-PRINCE, Haiti -- As the Haitian government struggles to bring security to its chaotic capital, many Haitians say the United States is aggravating the crime problem by quadrupling the number of criminal deportees to their native country.

Tensions have risen after a recent wave of kidnappings and high-profile slayings in Port-au-Prince, including the abduction, torture, and killing of a 20-year-old woman studying to be a teacher. It was in the midst of this rash of violent crime that the United States increased the deportation of Haitians, both illegal immigrants and legal-resident criminals who had served sentences, from 25 to 100 deportations per month, adding substantially to the more than 2,000 already deported to Haiti from the United States over the past five years.

The deportees have caused fear and anger, and spurred a debate over how to deal with them. Government officials favor jailing -- at least temporarily -- all deportees arriving in Haiti. But human rights leaders argue that such detentions are illegal and harmful and that what deportees need is help getting a foothold in Haitian society.

Some of the government's detractors call deportees a convenient scapegoat for officials under fire for failing to bring stability to the capital.

Haiti is not the largest recipient of US deportees in the Caribbean; Jamaica has had a consistently higher rate in spite of its smaller overall population. And many countries in the region have seen a steady rise in criminal deportations since the United States passed the Antiterrorism Act in 1996, making it harder for convicts to appeal deportation orders.

But Haiti, the poorest country in the hemisphere, has a weak police force, a barely existent judiciary, and overcrowded and unruly prisons. It is widely seen as ill equipped to deal with any extra bad apples. That's why the United States suspended criminal deportations to Haiti from 2005 into 2006, during the interim government that followed the bloody uprising and ouster of then-President Jean-Bertrand Aristide in 2004.

So why resume -- and quadruple -- the deportations? The US ambassador to Haiti, Janet Sanderson, told the Globe in December that there was a backlog of 450 Haitians in US jails who had served their time and could not be released onto American soil. She asserted that Haiti was a more stable place than it was a year ago.

The United States provided a $1 million grant for the International Organization for Migration and the Haitian government to provide services to deportees, including setting up a type of halfway-house program, to help them adjust to life in Haiti.

Despite such assistance, deportees are stigmatized as dangerous criminals. Although all of those convicted of a crime served their time in the United States, Haitian authorities continue to throw deportees deemed dangerous into prison and all others into police station holding cells upon arrival.

Government officials call the detentions a kind of "security quarantine" and say it is important for public safety. Some say this even while acknowledging that it violates the country's law against double jeopardy, and even as US officials urge the Haitian government to stop jailing deportees.

By the end of 2006, kidnapping and other violence in the already strife-ridden capital were soaring. In separate incidents in November and December, a senator and a former finance minister were kidnapped, a school bus was hijacked and the children on board abducted, and a 6-year-old boy and 20-year-old woman were kidnapped and killed. When the government came under attack from opposition political leaders and citizen protesters for failing to stop the terror, it had a new target for blame.

Prime Minister Jacques-Edouard Alexis told Parliament that he opposed the increase in deportations because, he said, deportees from the United States are significant contributors to Haiti's crime problem. And he announced that deportees were suspected in the high-profile murder of the 20-year-old student.

Foreign Minister Jean Raynald Clérismé, echoed Alexis's words. "These notorious criminals, were they not trained in the US?" he rhetorically asked Parliament. But some Haitians condemn the anti deportee rhetoric, calling it baseless and harmful.

"We've been asking the Haitian government for the statistics" to back up allegations that the deportees are contributing to rising crime, said Pierre Esperance, who heads the National Human Rights Defense Network, based in Port-au-Prince. "No one has the statistics. . . . The Haitian government has created a drama out of the issue of deportees."

Cheryl Little, a lawyer and executive director of the Florida Immigrant Advocacy Center, said that deportees are often mislabeled when they arrive in Haiti because authorities often look at their arrest records, which show charges but not convictions.

Many Haitians see the deportees as Americans, with their Haitian citizenship a mere technicality. By some estimates, the average deportee left Haiti before age 8 and was returned at least 20 years later. Many speak little Haitian Creole and have minimal familial, cultural, or emotional connection to the country. These differences make adapting more difficult, and worse: they make deportees quickly identifiable.

Harry Desiré, 36, called the recent inflammatory rhetoric about deportees not only misleading but also "very, very dangerous."

Desiré was deported to Haiti 12 years ago, after serving five years in New York State prisons for armed robbery. He said he once felt deportation was worse than staying in a US prison because deportees are so often targeted as scapegoats.

Desiré, who said he avoided detention when he arrived in Haiti by giving a police officer two pairs of sneakers, helped found Alternative Chance, a criminal deportee advocacy organization, in 1996. He and other deportee advocates warn of a major problem with Haiti's detention of the deportees: In the absence of friends and relatives, a deportee who might not have pursued a life of crime may have to turn to others in jail for help, thereby putting him on a criminal path.

Desiré says it's hard for deportees to grow out of their negative image. "Everybody, once they know you're a deportee, it's like you're automatically a criminal," he said. "So you could be innocent, going to church, but if you have a neighbor that doesn't like you, he can call the cops and tell lies, and the cops will believe him. . . . You really have to believe in yourself to survive."

© Copyright 2007 Globe Newspaper Company

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |