| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted January 22, 2007 |

In a Teenager's Plight, the Forgotten History of the 'Charity Girls' |

|

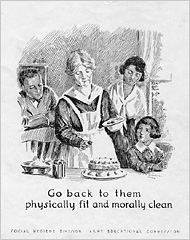

University of Minnesota Libraries, |

Social Welfare History Archives |

| A 1918 poster geared to soldiers. |

By DINITIA SMITH |

The writer Michael Lowenthal was reading through Susan Sontag’s essay “AIDS and Its Metaphors” when he first stumbled across a brief mention of the “charity girls.” He knew, he said, that he had to write a novel about them.

In what has remained a little-known episode in American history, close to 20,000 women, most of them infected with venereal diseases, were rounded up during and immediately after World War I and confined to prisons and reformatories without being formally charged with a crime.

Caught in periodic roundups of dance halls and wooded areas outside soldiers’ camps, some were prostitutes, others simply teenage girls attracted to the glamour of soldiers going off to war, or “charity girls” who had sex in exchange for meals or entertainment.

They were sometimes confined for a year or more, surrounded by barbed wire and guards. Often barred from contact with outsiders, the women were forced to undergo humiliating medical procedures.

This month Mr. Lowenthal’s book, “Charity Girl,” based on material he uncovered in government reports and social work journals, was published by Houghton Mifflin. “I decided I wanted to give these women the honor of imagining their situation,” Mr. Lowenthal said recently, “and empathizing with it.”

In “Charity Girl,” a 17-year-old immigrant named Frieda is a bundle wrapper at the Jordan Marsh department store in Boston. She has a brief sexual encounter with a soldier, Felix. When Felix seeks treatment for a venereal disease, he names Frieda as a sexual contact. Frieda is taken to an internment camp, where she is given medication; penicillin was not discovered yet, and instead substances like mercury, arsenic compounds, iodine and silver nitrate were used. Frieda is also put to work sewing, shoveling manure and gardening, and she is re-educated about the ills of the flesh in an effort to rehabilitate her.

| ________________________ | |

| A new novel explores a time when women with venereal disease were imprisoned. | |

| ________________________ |

As a work of literature, “Charity Girl” is in the vein of late-19th- and early-20th-century novels like “Sister Carrie,” which depicted the perils of big cities for young women. Department stores, especially, were places of temptation where unsupervised women came into contact with strange men and were exposed to the temptations of worldly goods.

Meanwhile, as America prepared to enter World War I, military men were undergoing comprehensive physical exams for the first time in American history, and doctors were shocked to discover a high incidence of venereal diseases among them.

Mothers petitioned President Woodrow Wilson to clamp down on the degeneracy. In Nancy K. Bristow’s book, “Making Men Moral: Social Engineering During the Great War,” she quotes a petition from the Ministerial Association and Christian Endeavor Convention, to Woodrow Wilson: “Keep our boys clean; not only from the ravages of the liquor traffic, but the scarlot (sic) woman as well.”

The petition continues: “Protect them from these foes that are more deadly than the armies of Europe.”

|

Eric Jacobs for The New York Times |

| Michael Lowenthal's new novel, "Charity Girl," explores a buried past. |

To cope with the problem, in 1917 Wilson created the Commission on Training Camp Activities, which undertook “purity campaigns” warning young men of disease. Red-light districts, including Storyville in New Orleans, were closed. “Moral zones” were created around military training camps from which women of ill repute were banned.

Athletic activities were instituted at the camps, since “severe muscular activity,” in the words of the commission, dampened male sexual urges. There were church services, chaperoned teas and lectures, all intended to fight the menace.

Yet the onus of responsibility for venereal diseases was put on women rather than men, as one pamphlet instructed soldiers: “Women who solicit soldiers for immoral purposes are usually disease spreaders and friends of the enemy.”

To help solve the “girl problem,” the government established the Committee on Protective Work for Girls. Protective workers scouted darkened areas around military camps trying to trap women consorting with soldiers. A special effort was made to spot couples having sex in taxis, one of the few places they could go near the camps for privacy.

In 1918 Congress passed the Chamberlain-Kahn Bill, allotting $1 million for a “civilian quarantine and isolation fund.” In “Charity Girl,” Frieda is interned in a former brothel, as were a number of women in real life.

All together, about 30,000 women were detained. Some were let go immediately. More than 18,000, however, were interned in federally financed facilities. Allan M. Brandt, an historian of medicine and science at Harvard University, and the author of “No Magic Bullet: a Social History of Venereal Disease in the United States Since 1880,” said the total number of those detained was actually far greater than federal records suggest because uncounted numbers of women were interned in local facilities.

According to those records, most of the women contacted and detained were first offenders. “There was such a wide dragnet of police and officials that it exhausted the supply of prostitutes,” Mr. Brandt said. “They were contacting women who might have engaged in prostitution, but had no record of it.”

Ms. Bristow quotes the chairman of the commission on training camp activities, Raymond B. Fosdick, as saying, “We are confronted with the problem of hundreds of young girls, not yet prostitutes, who seem to have become hysterical at the sight of buttons and uniforms.”

In the end, Mr. Brandt said, “these programs were really ineffective in controlling venereal disease.”

Both Mr. Lowenthal and Mr. Brandt pointed to parallels between the internment of women infected with venereal disease during World War I and the suggestion, during the early stages of the AIDS epidemic, that people with AIDS and H.I.V. be interned.

The World War I internments also reflected a national anxiety about changing sex roles, Mr. Brandt said. “They were part of a larger emergence of gender issues, of suffrage, women’s rights, women in the workplace, into the culture,” he noted.

In the end, Mr. Brandt said, the detainment of women with venereal diseases “was as much about the criminalization of female sexuality as it was about creating an effective public health program.”

“There is no evidence,” he said, “that it contributed to a more efficient, effective Army.”

Just why such a dramatic story has remained so little known for so many years is not entirely clear, but it may have had something to do with the patriotic fervor that surrounded the war effort and postwar eagerness to relegate such unpleasant stories to the past.

“There’s so much shame regarding issues of sexuality in general, and sexual diseases,” Mr. Lowenthal said. “I don’t think these women who went through it would have talked about it at the time."

And subsequent improvements in health care have also altered the public mood about diseases, Mr. Brandt said.

“After the age of antibiotics, whatever anxieties we had about sexually transmitted diseases receded, and we became focused on chronic diseases that were not communicable,” he said. “We grew up in an age where we were not that afraid of infection. Diseases like syphilis and gonorrhea provoke less anxiety and therefore less historical focus."

Copyright 2007 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, TheArts, of Saturday, January 20, 2007.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |