| Immigrants Deported, by U.S. Hospitals |

|

|

|

|

| Although the National Hospital of Orthopedics and

Rehabilitation is the only public rehabilitation hospital in Guatemala, it

dedicates just 32 beds to rehabilitation and does not offer the specialized

brain injury treatment that Mr. Jiménez needed. Photo: Josh Haner/The New

York Times |

|

|

|

| Half the hospital is devoted to orthopedic care and the

other half serves as an "asylum" for profoundly disabled Guatemalans. A few

weeks after he was brought there from Florida, the hospital discharged Mr.

Jiménez, transferring him to a public acute-care hospital, where his brother

found him "lying in the hallway on a stretcher, covered in his own

excrement." Photo: Josh Haner/The New York Times |

|

|

|

| Michael R. Banks, an estate-planning lawyer who represented

Mr. Jiménez in Florida, recently visited the National Hospital of

Orthopedics and Rehabilitation in Guatemala City on his way to meet with Mr.

Jiménez, who ended up with his elderly mother in a remote mountain village.

Photo: Josh Haner/The New York Times |

|

|

|

| Diana Gregory, the nurse from Martin Memorial who

accompanied Mr. Jiménez back to Guatemala, said that she was impressed by

the hospital she left him at in Guatemala City. "Their equipment looks like

it could have been donated to the Smithsonian but it was functioning

equipment and they used it," she said, adding: "That facility could have

taken care of me any day." Photo: Josh Haner/The New York Times |

|

|

|

| After Mr. Jiménez arrived, the Guatemalan hospital

contacted his common-law wife, Fabiana Domingo Laureano, who lived in

Antigua, Guatemala, with their two young sons, and asked her to come get

him. Ms. Domingo, who was 27 at the time, was shocked to learn that her

husband was back and terrified by the request. Then as now, she was eking

out a living, selling traditional woven clothing in the municipal

marketplace while sharing a spare, concrete room with her sons in her

parents' humble home. "I was already living from hand to mouth," she said.

"How could I possibly have given him what he needs?" Photo: Josh Haner/The

New York Times |

|

|

|

| With no other options, Mr. Jiménez's family brought him

back to his home, outside the provincial city of Soloma. No medical care for

his condition is available. Photo: Josh Haner/The New York Times |

|

|

|

|

| From Soloma, the road to Mr. Jiménez's hamlet only goes so

far, and the trip must be completed on foot, up and down a rutted dirt path

through goat-strewn meadows. Photo: Josh Haner/The New York Times |

|

|

|

| The New York Times took the trek to visit him in late

June, Mr. Jiménez had not budged from his hilltop home since

returning there and no medical professional had visited him, either.

With his mother too frail to move him into his wheelchair, his life

had shrunken to the confines of his bed, across from his mother's.

Only the presence of visitors, who could help him into his

wheelchair, gave Mr. Jiménez a rare chance to get out of bed. Photo:

Josh Haner/The New York Times |

|

|

|

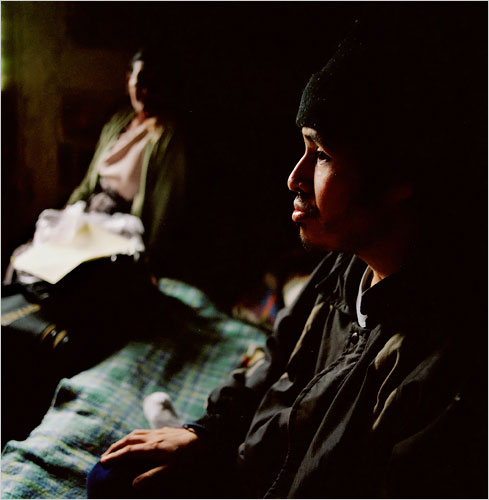

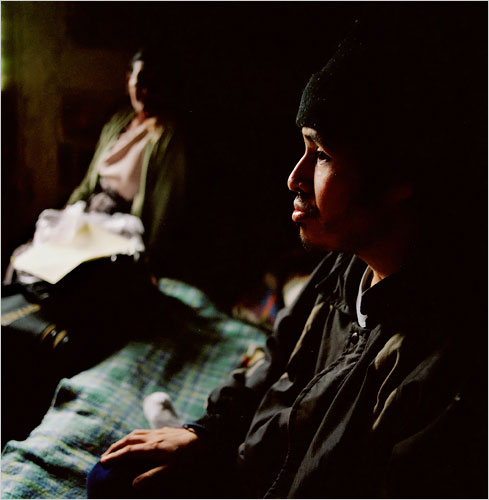

| Since being hoisted in his wheelchair up a steep slope to his

remote home, Mr. Jiménez, who suffered a severe traumatic brain

injury, has received no medical care or medication -- just Alka

Seltzer and prayer, his 72-year-old mother, Petrona Gervacio Gaspar,

said. Photo: Josh Haner/The New York Times |

|

|

|

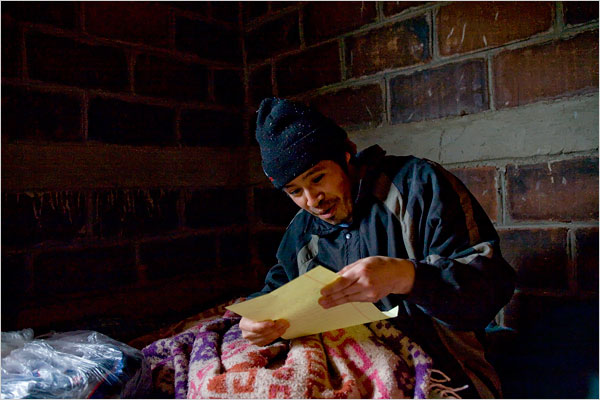

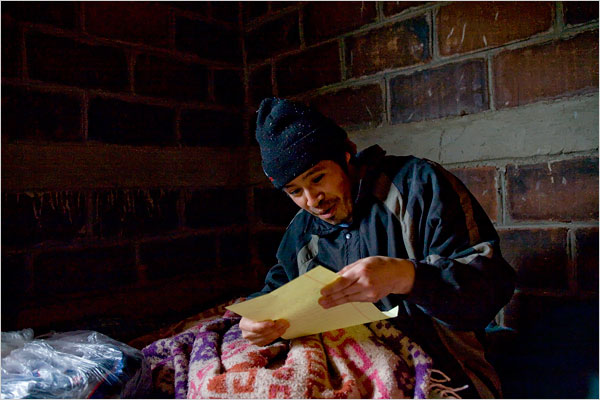

| To the surprise of his visitors, Mr. Jiménez, despite

his background and brain injury, was able, and eager, to

read a letter from his cousins in Florida. At first, Mr.

Jiménez read haltingly, then more fluidly. Later, when all

his visitors had gone outside, he picked up the letter and

read the ending aloud again to himself, softly. "I want to

tell you," he read, "that we miss you and love you. May God

continue to bless you." Mr. Jiménez smiled, and repeated,

"May God continue to bless you." Photo: Josh Haner/The New

York Times

|

|

|

|

|

|

| With no access to medical care, Mr. Jiménez has suffered since

returning home. Over the last year, his condition has deteriorated

with routine and violent seizures, characterized by falls,

protracted convulsions, a loud gurgling in the throat, the vomiting

of blood and, finally, a collapse into unconsciousness. "Each time

he loses a little more of himself," his mother said. Photo: Josh

Haner/The New York Times |

|

|

|