| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted August 15, 2003 |

Idi Amin, Brutal Ruler of Uganda in the 70s, dies |

|

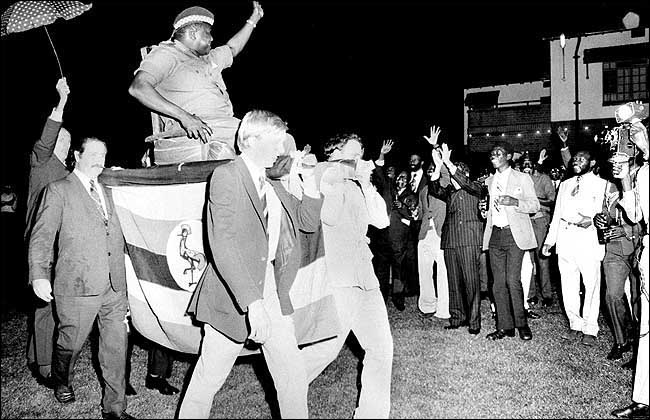

| Mr. Amin is carried by four British businessmen during a party for diplomats in 1975. A Swedish businessman holds an umbrella in the manner of servants who once shielded tribal rulers from the sun. (AP Photo) More photos |

By MICHAEL T. KAUFMAN |

IDI Amin, whose eight-year reign of terror in Uganda encompassed widespread killing, torture and dispossession of multitudes and left the country pauperized, died yesterday in Jidda, Saudi Arabia, where he had lived for years in exile. He was believed to have been about 78 years old, though some reports said he was as old as 80.

Mr. Amin had been hospitalized and on life support since mid-July. He died from multiple organ failure, Reuters reported.

For much of the 1970's, the beefy, sadistic and telegenic despot had reveled in the spotlight of world attention as he flaunted his tyrannical power, hurled outlandish insults at world leaders and staged pompous displays of majesty.

By contrast, his later years were spent in enforced isolation as the Saudi Arabian authorities made sure he maintained a low profile. Mr. Amin, a convert to Islam, his four wives and more than 30 children fled Uganda just ahead of an invading force of Ugandan exiles and Tanzanian troops that overthrew his government. They went first to Libya, and eventually to Saudi Arabia.

By the time he had escaped with his life, the devastation he had wreaked lay fully exposed in the scarred ruins of Uganda. The number of people he caused to be killed has been tabulated by exiles and international human rights groups as close to 300,000 out of a total population of 12 million.

Those murdered were mostly anonymous people: farmers, students, clerks and shopkeepers who were shot or forced to bludgeon one another to death by members of death squads, including the chillingly named Public Safety Unit and the State Research Bureau. Along with the military police, these forces numbering 18,000 men were recruited largely from Mr. Amin's home region. They often chose their victims because they wanted their money, houses or women, or because the tribal groups the victims belonged to were marked for humiliation.

But there were also many hundreds of prominent men and women among the dead. Their killings were public affairs carried out in ways that were meant to attract attention, terrorize the living and convey the message that it was Mr. Amin who wanted them killed. They included cabinet ministers, Supreme Court judges, diplomats, university rectors, educators, prominent Catholic and Anglican churchmen, hospital directors, surgeons, bankers, tribal leaders and business executives.

In addition to Ugandans, the dead also included some foreigners, among them Dora Bloch, a 73-year-old woman. She was dragged from a Kampala hospital and killed in 1976 after Israeli commandoes raided Entebbe Airport to rescue 100 other Israelis who along with her had been taken as hostages from a hijacked Air France plane.

As an awareness of spreading horror and suffering filtered out of Uganda, Mr. Amin began to address the criticism, choosing words that intentionally added insult to injury. He declared that Hitler had been right to kill six million Jews. Having already called Julius Nyerere, then the president of Tanzania, a coward, an old woman and a prostitute, he announced that he loved Mr. Nyerere and "would have married him if he had been a woman." He called Kenneth Kaunda, then the president of Zambia, an "imperialist puppet and bootlicker" and Henry A. Kissinger "a murderer and a spy." He said he expected Queen Elizabeth to send him " her 25-year-old knickers" in celebration of the silver anniversary of her coronation.

In other comments he offered to become king of Scotland and lead his Celtic subjects to independence from Britain. He forced white residents of Kampala to carry him on a throne and kneel before him as photographers captured the moment for the world to see. He also ejected Peace Corps volunteers and the United States marines who had guarded the American Embassy in Kampala.

Mr. Amin's flagrant brutality, coupled with his seemingly erratic behavior and calculating insults, aroused disgust but also fascination far beyond Uganda's borders. Some African nationalists cheered his insults of Europeans. Radical Arabs, led by Muammar el-Qaddafi of Libya, actively courted him as an ally, and for a time so did the Soviet Union. But there were others who questioned his sanity. Harold Wilson, the leader of the British Labor Party, called him "mentally unbalanced." Mr. Kaunda described him as "a madman, a buffoon."

Many, however, who had observed him long and carefully from close quarters warned against such judgments. "Capricious, impulsive, violent and aggressive he certainly is, but to dismiss him as just plain crazy is to underestimate his shrewdness, his ruthless cunning and his capacity to consolidate power with calculated terror," wrote Christopher Munnion, a reporter for The Daily Telegraph, after he was detained at the notorious Makindye military barracks, where four of his cellmates, former police officers, were killed with sledge hammers.

Like many African leaders including Mr. Nyerere and Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya, Idi Amin never knew the date of his birth. According to his army documents, he was born around 1925 in a remote northwestern region near the borders of Sudan and Congo, while Uganda was under British control. His father was a farmer of the small Kakwa tribe and his mother was from the linked Lugbara people. The region is ethnically distinct from the rest of Uganda, with many people, like the Amin family, having close ties to tribesmen in Sudan. Ugandans referred to these northern tribes collectively as Nubians, and it was upon such Nubians that Mr. Amin would later rely for his security forces.

Soon after his birth, his parents separated, and his mother took her child to live in Nubian settlements in Ugandan cities. At one point she worked as a cane cutter on a plantation that her son would, as president, appropriate from its Asian owners.

Her son joined the King's African Rifles in 1946 as an assistant cook. Later, after he had given himself the rank of field marshal and covered his massive chest with medals, he would claim that he had fought with the unit in Burma, but there is no record of such combat. Yet the powerful Amin, 6 feet 4 inches, quickly attracted the attention of British commanders.

As a young soldier he rose steadily through the ranks, spending the mid-1950's fighting in colonial Kenya against Mau Mau guerrillas who used terror tactics to spread dread among white settlers in hopes of ending British rule. In 1957 he was promoted to sergeant major and two years later was singled out for the rank of "effendi," a new position for native noncommissioned officers judged to have leadership potential.

There were a few blots in his record book. He was charged with failing to obtain treatment for venereal disease. This might have been the basis of allegations that his erratic behavior reflected the mental degeneration of untreated syphilis. More serious were allegations that a unit under his command had killed desert tribesmen. Still, when Uganda became independent in 1962, Mr. Amin held the highest rank of any African in the Ugandan military.

He was on very good terms with Milton Obote, the country's first prime minister, who in 1963 approved his promotion to major. Mr. Amin was sent for special training to Britain and Israel, where he gained his paratrooper wings. In 1964 he was promoted to colonel and appointed deputy commander of Uganda's army and air force.

In February 1966, charges were raised in Uganda's Parliament that two years earlier Mr. Amin, carrying out Mr. Obote's orders, had misappropriated $350,000 in gold and ivory from guerrillas in Congo who he was supposed to have supplied with arms. Mr. Amin's forces arrested the five ministers who raised the issue and Mr. Obote suspended the Constitution. Two days later Mr. Amin was put in full charge of all the military and the police.

Two months later, Mr. Obote annulled Uganda's basic political formulation under which power was shared between himself and Mutesa II, the king of the Baganda, long the country's most powerful tribe. Mr. Amin sent tanks to shell the palace of the king, who escaped and fled to London.

In 1967, Mr. Amin was promoted to brigadier general and the next year to major general. As Mr. Obote declared a turning to the left and sought to remove influential Bagandas and replace them with his own ethnic kin from the Acholi and Langi tribes, he and Mr. Amin worked closely together.

But in 1971, Mr. Obote, believing that his top general had been plotting behind his back, sought to rein him in. As he left for a conference in Singapore, Mr. Obote ordered Mr. Amin to prepare an accounting of several million dollars in defense spending. Mr. Obote never returned to his presidential residence. On Jan. 25, while he was flying back from Singapore, Mr. Amin seized power. Mr. Obote eventually made his way to Tanzania, where he would later denounce his former ally as "the greatest brute an African mother has ever brought to life."

Inside the country, crowds danced and toasted the new leader. Outside Uganda, Mr. Amin was also applauded. In light of Mr. Obote's announced plans to nationalize British-held property, the reaction in London was favorable. The Israelis, who had large building projects in Uganda and who had worked closely with Mr. Amin, also believed they would benefit by the change.

Ethnic conflicts soon spread through the army, with Mr. Amin's Nubian supporters killing a few thousand soldiers from the Acholi and Langi tribes. The economy deteriorated as Mr. Amin ordered more money printed to cover expenditures. In 1972 he asked the Israelis for more money and jet fighters, saying he needed them to deal with Tanzania, where Mr. Obote was living. When the Israelis dismissed the request, he traveled to Libya and obtained promises of aid from Colonel Qaddafi. He then ordered 500 Israelis out of the country, ending several large building projects, and began his fulminations against Zionism and Jews.

On Aug. 5, 1972, with the economy continuing to falter, Mr. Amin announced that all Ugandans of Asian origin holding British passports, some 40,000 in all, would have to leave the country within 90 days. The majority of them were third-generation descendants of workers brought by the British from the Indian subcontinent. Most of those expelled left for Britain. They were allowed to take only what they could carry.

In the middle of the exodus, Mr. Obote's backers mounted an ineffective invasion from Tanzania. It was soon repulsed, but it provided a pretext for increasing terror, beatings and murders of Ugandans.

A special vocabulary of killing and torture was developed and used by Mr. Amin, according to his former associates who managed to escape. "Giving the V.I.P. treatment" to someone meant to kill, as did the instruction "Go with him to where he sleeps." "Giving tea" meant whipping and dismemberment.

On June 27, 1976, seven terrorists, two of them members of the German Baader-Meinhof gang, hijacked Air France Flight 139 after it left Tel Aviv for Paris. The plane landed first in Benghazi, Libya, and then continued on to Entebbe in Uganda, where it arrived early on June 28.

On the morning of July 4, Israeli commandoes killed the hijackers, rescued 102 hostages and destroyed eight Ugandan Air Force MIG's. The raid on Entebbe left Mr. Amin with few options for retaliation beyond killing Mrs. Bloch, who days before the rescue had been taken to hospital when some food stuck in her throat.

In 1978, Mr. Amin sent troops into Tanzania in an effort to annex the Kagera salient, a desolate spur to the west of Lake Victoria. By early 1979, they fled under the assault of Tanzanian forces and Ugandan exiles. Mr. Amin's army and its Libyan allies were unable to stop the counteroffensive, and on April 12 Kampala was taken. Mr. Amin fled, first to Tripoli in Libya and finally to Saudi Arabia.

He remained there until January 1989, when he slipped out on a false passport and flew to Kinshasa in what was then Zaire, where he claimed he would return to Uganda to reclaim power. The Zairean authorities held him while he looked for someplace that would take him. The Ugandan government said it would accept him only to stand trial. No other country would take him, and ultimately Saudi Arabia, which had also sought to keep him from returning there, reversed itself and once more provided him with sanctuary. Since then he had lived in Riyadh, where he was occasionally seen driving a white Chevrolet.

Copyright 2003 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, International, of August 16, 2003.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |