| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted December 20, 2003 |

How to Save the World? Treat It Like a Business |

|

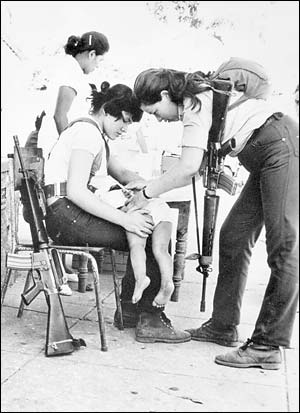

Baltazar/Unicef, 1985 |

| The cease-fire to allow for child vaccinations El Salvador's civil war based on the global health-care ideas of social entrepreneurs. |

| By EMILY EAKIN |

Ohen J. B. Schramm talks about getting poor kids into college, he sounds less like a bleeding heart than a corporate shark pitching a moneymaking scheme. He talks about market opportunities, about talent that is "undervalued by the marketplace" and "economic muscle that's not being harnessed."

Mr. Schramm, a divinity school graduate, is the founder of College Summit, an organization in Washington that helps low-income high school students with B and C averages, who might not otherwise continue their educations, apply to college. As schooled in the science — and lingo — of market domination as any well-trained M.B.A., he wants to eliminate what he calls the college "market gap" and put a dent in the poverty rate at the same time. And not just in his community but in the nation at large.

"A kid who enrolls in college over the course of his life contributes $300,000 more in federal taxes alone and a million more in lifetime earnings," Mr. Schramm explained. "And getting that kid who's the first in his family to go to college effectively ends poverty in that family. That's irreversible progress."

The work is slow going and unglamorous. It has not made him famous or rich. But as faith in the ability of government and private philanthropy to solve social problems diminishes, unconventional do-gooders like Mr. Schramm, who combine market savvy and a social conscience with an overweening ambition to see their ideas become part of the cultural bedrock, belong to an important global trend.

If Mother Teresa, who won a Nobel Peace Prize for her charitable work with the poor and the sick, embodies the old way of treating social problems (compassion and Band-Aids), then big thinking, solution-minded pragmatists like Mr. Schramm represent the new. According to the theory emerging from some of the nation's top business schools, they belong to a powerful and growing breed of innovator: the social entrepreneur.

| _______________________ |

| Social entrepreneurs are part of a new wave that mixes capitalism with conscience. |

| _______________________ |

"We need innovative solutions to social problems, and increasingly societies are realizing that private citizens, acting in entrepreneurial ways, blending business tools with relevant social expertise, are the best hope for finding those solutions," said J. Gregory Dees, director of the Center for the Advancement of Social Entrepreneurship at the Fuqua School of Business at Duke University and a leading expert in the budding field. "These citizens are social entrepreneurs."

In New York City there is Sara Horowitz, a lawyer and labor activist, who started Working Today, a group that provides low-cost health insurance to freelancers, who typically have little access to benefits but who now make up nearly a third of the labor force. Better known are Wendy Kopp, the founder of Teach for America, which hires young graduates from top colleges to teach in deprived urban and rural schools; Paul Farmer, a doctor who is transforming global health-care policy toward the indigent; and Muhammad Yunus, a Bangladeshi economist who revolutionized the concept of micro-credit, making millions of successful small loans to poor people through his Grameen Bank.

|

| Elizabeth Lippman for the New York Times |

| William Drayton, founder of Ashoka, an organization that gives funds and professional support to social entrepreneurs. |

William Drayton, the founder of Ashoka, an organization that since 1981 has provided funds and intellectual support to just such citizens around the world, has perhaps done more than anyone to encourage the trend. And he speaks of it with near revolutionary fervor. Rattling off impressive statistics about the growth of nonprofit and citizen groups in the last two decades, he declares social entrepreneurship to be "the most important historical force at work today," adding, "The social half of society has tipped: it has become as entrepreneurial and competitive as the business half of society, and the consequences are extremely dramatic."

Given the flurry of interest in the subject at business schools, that may prove not to be such an exaggeration. In 1989, when Mr. Dees, then a professor at the Harvard Business School, first proposed a course in social entrepreneurship, he was flatly turned down. "The reaction was very cool," he recalled. "I was cautioned not to do that."

But by the mid-1990's the attitude on campus had changed. Harvard created an initiative in social entrepreneurship, and Mr. Dees taught what he thinks may have been the first course on the topic in an American business school.

Today there are similar initiatives at Columbia, Stanford, Duke and Yale, and the Web site of the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (aacsb.edu), an international accrediting agency, lists 28 other schools that say they have programs in social entrepreneurship. Last spring Stanford started the first academic journal dedicated to the subject: The Stanford Social Innovation Review. And in November the Saïd Business School at Oxford University inaugurated the Skoll Center for Social Entrepreneurship, named for Jeff Skoll, the former president of e-Bay and a major financial backer.

While the activities of some social entrepreneurs and their organizations have received news media attention, the press has been slow to pick up on the larger phenomenon. But that, too, is beginning to change. The January issue of Fast Company features the winners of that magazine's first annual Social Capitalists Awards: 20 organizations that are "using the disciplines of the corporate world to tackle daunting social problems." And in February Oxford University Press will publish "How to Change the World: Social Entrepreneurship and the Power of New Ideas," by David Bornstein, a journalist whose specialty is social innovation.

His first book, "The Price of a Dream" (Simon & Schuster, 1996), recounted Mr. Yunus's successful experiment with micro-credit and eventually led him to Mr. Drayton, whom he calls "the social entrepreneur of social entrepreneurship." For his new book Mr. Bornstein interviewed 100 social entrepreneurs in a dozen countries and ended up using 8 as case studies: Mr. Drayton and Mr. Schramm, along with those from other countries, like Fábio Rosa, a Brazilian engineer who hit on a strategy to provide cheap electricity to that country's rural farmers.

Like Mr. Drayton, Mr. Bornstein cites the rise of citizen organizations around the world as a crucial development: more than a million in India, 12,000 in Slovakia, 400,000 in Brazil. Even in the United States, where there is a strong tradition of such groups, he notes, the number registered with the Internal Revenue Service jumped 60 percent between 1989 and 1998, to 734,000.

But such activity, he argues, is merely the backdrop against which social entrepreneurship should be viewed. Many nonprofit groups have incorporated smart business tactics — like having a profit arm — into their daily operations, he points out. (And many business schools emphasize such strategies in their courses.) But this alone does not mean that there is a social entrepreneur at the helm.

True social entrepreneurs are "transformative forces," he writes: "People with new ideas to address major problems who are so relentless in the pursuit of their visions that they will not give up until they have spread their ideas everywhere."

By that definition such people have always been around. Mr. Bornstein devotes a chapter to Florence Nightingale, whose crusade to introduce hygiene and sanitation standards in Victorian hospitals led to dramatic declines in mortality. And Mr. Drayton cites William Lloyd Garrison, the 19th-century abolitionist leader. But only recently, they argue, have social conditions enabled such innovative "change makers" to succeed in significant numbers.

Well into the 18th century, concepts like innovation and competition hardly existed, even in the business sector. Trades were frequently controlled by guilds that forbade competition, governments awarded monopolies and subsidies at whim, and a thicket of regressive laws explicitly discouraged innovation.

By 1800, however, the French economist Jean-Baptiste Say, a free-market enthusiast who translated Adam Smith's "Wealth of Nations," had designated a new term for the kind of businessman who was reinventing the economy: entrepreneur, whom he defined as someone "who shifts economic resources out of an area of lower and into an area of higher productivity and greater yield."

While the business world was being transformed, becoming innovative and competitive, the social sector failed to follow suit. It didn't need to. As Mr. Drayton succinctly put it, "Government made it unnecessary." As long as states were able to take care of social services — like schools, hospitals, public transportation and garbage removal — there were few incentives for private citizens to compete for the tasks.

Today, however, that is clearly no longer the case. In democratic societies the welfare net is fraying. And elsewhere in the world, communist and authoritarian regimes have collapsed, giving ordinary citizens the freedom and impetus to make big social changes. It doesn't hurt, Mr. Bornstein adds, that per capita income in free-market countries increased by several hundred percent in the 20th century, allowing more people to opt for careers in lower-paying, nonprofit work. Or that life spans have increased, along with literacy and education rates and access to information. As he puts it, "citizens have become acutely conscious of environmental destruction, entrenched poverty, health catastrophes, human-rights abuses, failing education systems and escalating violence," and more of them "have the freedom, time, wealth, health, exposure, social mobility and confidence" to do something about it.

Social entrepreneurship sounds wonderful. Listening to Mr. Drayton, for example, it is easy to feel almost giddy. "This is going at a historic rate of speed that is unprecedented," he insists. "The agricultural revolution took 12,000 years. This has taken two and a half decades."

But while welcoming the trend, some experts caution against viewing social entrepreneurship as a panacea. "We see a lot of major successes in social entrepreneurship, and we're seeing more space for it in some societies," said the economist Jeffrey D. Sachs, director of the Earth Institute at Columbia University. "But we cannot simply rely on social entrepreneurship for what the government needs to do. We also have an enormously efficient private sector. We shouldn't dismiss the importance of the profit motive in generating a lot of things we count on as basic to our life. The social sector must work alongside the public and private sectors."

Copyright 2003 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Arts & Ideas, of December 20, 2003.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |