| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

More Special Reports |

| Posted June 19, 2006 |

| Here Illegally, Working Hard And Paying Taxes |

|

Photographs by Allen Brisson-Smith for The New York Times |

| Polo, an illegal immigrant, cleans buildings in Minneapolis for ABM Industries. He earns $11.75 an hour, with health and vacation benefits. |

By EDUARDO PORTER |

MINNEAPOLIS — It is 5:30 in the evening as Adriana makes her way to work against a flow of people streaming out of the lattice of downtown stores and office towers here. She punches a time card, dons a uniform and sets out to clean her first bathroom of the night. Skip to next paragraph Multimedia

A few miles away, Ana arrives at a suburban Target store at 10 p.m. to clean the in-house restaurant for the next day's shoppers. At 5:30 the next morning, Emilio starts his rounds at the changing rooms at a suburban department store. A half-hour later, Polo rushes to clean the showers and locker room at a university here before the early birds in the pool finish their morning swim.

____________ |

|

Most Immigrants Are Now Being Hired by Established Firms. |

|

____________ |

Adriana, 27; Ana, 27; Emilio, 48; and Polo, 52, are all illegal immigrants, denizens of one of the most easily overlooked corners of the nation's labor force and almost universally ignored by the workers, shoppers and students they clean up after.

"It's like you are invisible," Adriana said.

Invisible, perhaps, but not hidden. In contrast to the typical image of an illegal immigrant — paid in cash, working under the table for small-scale labor contractors on a California farm or a suburban construction site — a majority now work for mainstream companies, not fly-by-night operators, and are hired and paid like any other American worker.

Polo — who, like all the workers named in this article, agreed to be interviewed only if his full identity was protected — is employed by a subsidiary of ABM Industries, a publicly traded company based in San Francisco with 73,000 workers across the country and annual revenues of $2.6 billion. Emilio works for the Kimco Corporation, a large private company with 5,000 employees in 30 states and sales of about $100 million.

More than half of the estimated seven million immigrants toiling illegally in the United States get a regular paycheck every week or two, experts say. At the end of the year they receive a W-2 form. Come April 15, many file income tax returns using special ID numbers issued by the Internal Revenue Service so foreigners can pay taxes. Some even get a refund check in the mail.

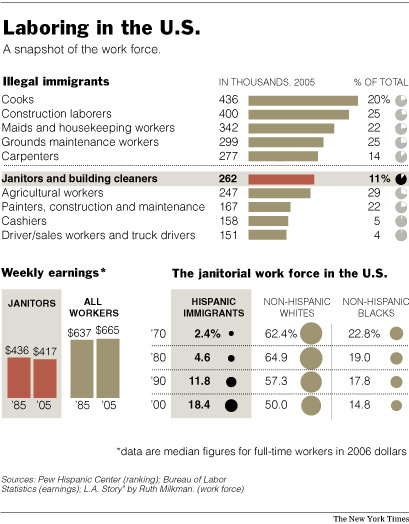

And they are now present in low-skilled jobs across the country. Illegal immigrants account for 12 percent of workers in food preparation occupations, for instance, according to an analysis of census data by the Pew Hispanic Center. In total, they account for an estimated one in 20 workers in the United States.

The building maintenance industry — a highly competitive business where the company with the lowest labor costs tends to win the contract — has welcomed them with open arms. According to the Pew Hispanic Center, more than a quarter of a million illegal immigrants are janitors, 350,000 are maids and housekeepers and 300,000 are groundskeepers.

The janitorial industry has been transformed in recent years as a handful of companies have consolidated by taking over hundreds of small local operators. That activity has gone hand-in-hand with the steady advance of immigrants, legal and illegal — almost all of them Hispanic — who have been drawn into what was once an overwhelmingly American-born work force.

Adriana works for Harvard Maintenance, a New York contractor that has some 3,700 janitors and cleans landmarks like Yankee Stadium and Shea Stadium. ABM Industries, Polo's employer, is the biggest contractor in Minneapolis and St. Paul, with about 35 percent of the market and a portfolio of high-profile customers that include the Minneapolis-Saint Paul International Airport and some downtown buildings.

ABM is a coast-to-coast force in the business, responsible for cleaning a virtual Who's Who of the nation's best-known buildings, at one time even including the World Trade Center in New York, where several illegal janitors died on 9/11.

Despite a murky legal status, ABM hired Polo just as it would hire any other worker. His wife and daughter — who already worked at the university — recommended him to their supervisor, who collected Polo's application and paperwork, gave him an ABM uniform and put him on the payroll. He makes $11.75 an hour, has health insurance and gets two weeks of paid vacation every year.

The Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 made it a crime for companies to knowingly hire illegal immigrants. Employers say they do their utmost to comply.

"We don't ever knowingly hire undocumented workers," said Amy Polakow, a spokeswoman for Kimco.

Harvard Maintenance issued a statement: "While we are dismayed that an employee allegedly has submitted fraudulent documentation," it said, "we screen all new hires and make sure they provide proper paperwork."

| Buying the Documents |

A written statement from ABM said that "if an individual were found to have presented falsified work authorization documents to gain employment, their employment would be terminated."

Still, in many cities it would be hard to put together a cleaning crew without resorting to an illegal work force.

Adriana used to work for ABM too, she said. But last year Harvard Maintenance, a rival contractor that entered the Minneapolis market two years ago, won the contract to clean her building. Adriana guesses that except for a couple of legal immigrants from Ecuador and a couple of Somalis, the rest of the three dozen or so janitors on her shift are illegal immigrants.

|

And when the contractor changed, the work force in her building did not. "All the workers," Adriana said, "are the same ones."

Illegal immigrants operate in a kind of parallel employment universe, structured in many ways like the legal job market but with its own rules and procedures.

To begin with, acquiring the necessary documentation to work is a routine transaction these days. In Minneapolis, one only has to mill about for a few minutes in a Kmart parking lot known to immigrants and a young Guatemalan with a Patrón tequila hat will approach on his bike and quietly offer to help.

A set of Polaroid photos can be purchased for $10 at the photo outlet- sporting goods store up the street — a quick snap against a white backdrop tucked among the soccer balls and jerseys of national squads from all over the world.

The documents themselves cost $110. Within two hours of having received the photos, the Guatemalan is cycling back into the parking lot to make the drop of the ID package. It includes a green card with the customer's photo and somebody's fingerprints, along with a Social Security card, for which the number was plucked out of thin air.

Some illegal immigrants do not even need the green card. Until the late 1990's, Mexican illegal immigrants typically arrived in Minnesota with their birth certificate and Mexican voting card, which could be used to obtain a legal Minnesota state ID.

But getting a Social Security number could be a little more complicated in the old days. Lily, 38, another janitor cleaning a building downtown, knew no one in Minneapolis when she arrived illegally from Guatemala 14 years ago. So when a neighbor said she needed papers, she called the smuggler who brought her across the border at his home in Mexico.

He asked her to make up a nine-digit number, which she did by combining the date she left Guatemala and the date she arrived in the United States two months later. She sent him some photos and $75 and received her fake papers by return mail.

Documents in hand, getting a job is straightforward. A common first step for new immigrants is to apply to a temporary work agency for the first job. But as immigrant communities have grown, new arrivals have been able to tap into networks of friends, relatives and former neighbors to help them navigate the United States and jump straight into a permanent job.

When Adriana and her sister arrived in Minneapolis from Mexico in 1998, their mother was waiting for them. She paid the smuggling fee of $1,700 per person and helped Adriana into her first job at the building where she worked and where she knew the supervisor well.

"You know, it's the chain," Adriana said. "I just got a job in my building for a cousin."

In some industries with many illegal immigrants, like construction, farming and landscaping, employers often turn to labor contractors to assemble crews of workers — transferring onto them the responsibility of checking the paperwork. That helps establish deniability in case of an immigration raid.

|

| Adriana works for Harvard Maintenance cleaning buildings. She said most of the co-workers on her shift were illegal immigrants, too. |

By contrast, the big building maintenance contractors do much of the hiring themselves. But some still distance themselves from the job market itself by delegating hiring to supervisors in individual buildings — often immigrants themselves — who will receive the job applications, help fill in official documents and copy supporting papers.

Adriana said she never had to step into ABM's offices, which are across the Mississippi River from downtown Minneapolis. She said that the supervisor knew she did not have proper papers.

| Cheaper Labor |

Starting about 30 years ago, as illegal immigration began to swell, building maintenance contractors in big immigrant hubs like Los Angeles started hiring the new immigrant workers as part of a broader effort to drive down labor costs. Unions for janitors fell apart as landlords shifted to cheaper nonunion contractors to clean their buildings. Wages fell and many American-born workers left the industry.

Between 1970 and 2000, the share of Hispanic immigrants among janitors in Los Angeles jumped from 10 percent to more than 60 percent, according to a forthcoming book by Ruth Milkman, a sociologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, titled "L.A. Story: Work, Immigration and Unionism in America's Second City." (Russell Sage Foundation, August 2006.)

The pattern repeated itself as immigrants spread throughout the rest of the country. By 2000, Hispanic immigrants made up nearly 1 in 5 janitors in the United States, according to Ms. Milkman's research, up from fewer than 1 in 20 in 1980.

When the Service Employees International Union started to reorganize the industry in the late 1990's, it adapted its approach in some cities to appeal to illegal workers. For instance, union contracts in Los Angeles include clauses instructing employers to contact the union if an immigration official "appears on or near the premises" and barring the employers from revealing a worker's name or address to immigration authorities.

Building maintenance contractors and those who contract their services underscore their efforts to keep illegal immigrants off the payroll. But beyond that they are reluctant to discuss the presence of illegal immigrants in the janitorial work force.

In a statement, Target pointed out that its stores were cleaned by outside contractors. "As in the past," it read, "if we find any illegal behavior by our vendor, we will immediately terminate their contract."

Mr. Mitchell said ABM had "put in place policies, procedures and ongoing managerial training for compliance with immigration law." Harvard Maintenance's statement added that "we believe our screening programs currently in place are among the best in the building services industry."

For all these efforts, however, it is remarkably easy for illegal immigrants to get a regular, above-board job.

The law requires employers to make workers fill out I-9 "employment eligibility" forms and provide documents to prove they are legally entitled to work.

But the employers benefit from one large loophole: they are not expected to distinguish between a fake ID and the real thing. To work, illegal immigrants do not need to come up with masterpieces of ID fraud, only something that looks plausible. "To bring a criminal prosecution we need to show an employer knowingly hired an illegal immigrant," said Dean Boyd, a spokesman at Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the branch of the Department of Homeland Security that enforces immigration rules. " 'Knowingly' is the key word."Yet the standard of plausibility is not particularly tight. "Some of these documents are so visibly wrong that you don't need to be an expert on what a Social Security card looks like," said Michael Mahdesian, chairman of the board of Servicon Systems, a private contractor that cleans aerospace and defense facilities as well as office buildings in California, Arizona and New Mexico.

Mr. Mahdesian said Servicon was more careful than other contractors — forced by the nature of its clients in the military industry to make more rigorous checks to keep illegal immigrants out. But he said that each time Servicon took over a cleaning contract in a new office building, it found that 25 percent to 30 percent of the workers it inherited from the previous contractor were working illegally, and had to let them go.

"Most companies in this industry doing commercial office buildings take the view that it is not their job to be the immigration service," Mr. Mahdesian said.

Companies have little to fear. The penalty for knowingly hiring illegal immigrants includes up to six months in jail — or up to five years in particularly egregious cases — and fines that range from $275 to $11,000 for each worker. Yet fines are typically negotiated down, and employers are almost always let off the hook. Only 46 people were convicted in 2004 for hiring illegal immigrants; the annual number has been roughly the same for the last decade.

In a rare raid, about 50 illegal workers — including a handful of ABM janitors — were arrested at the Minneapolis-St. Paul airport in 2002, according to Tim Counts, a spokesman for the Minnesota office of immigration and customs enforcement. With one exception — the Wok & Roll Chinese restaurant in the airport terminal — no charges were brought against the companies that hired them, Mr. Counts said.

| Pushing for Unionization |

Despite becoming a fixture of the labor market, illegal immigrants remain vulnerable at work. Wages declined as illegal immigrants entered the janitorial labor pool. Janitors' median earnings fell by 3 percent in real terms between 1983 and 2002, when the Labor Department changed the definitions of building maintenance jobs and other occupations.

Meanwhile, earnings across all occupations rose by 8 percent, after accounting for inflation. Though unionization has helped push janitors wages back up in many cities, they remain lower in markets with many illegal immigrants in the labor force.

In New York City, janitors cleaning commercial buildings make $19 an hour. Mike Fishman, president of the Service Employees International Union's local in New York, points out that the union never lost ground in the city, and it is still unusual to find illegal immigrants cleaning office buildings there.

In Southern California, by contrast, unions were decimated in the 1980's, and only started recovering in the late 1990's. According to Mike Garcia, president of the union's main local in the state, Southern California's unionized janitors earn between $8.50 and $11 an hour.

Unscrupulous employers still victimize illegal workers frequently. Veronica, a 39-year old illegal immigrant from Mexico, had been working for a temporary employment agency for about a year, crating boxes of beauty products for Aveda, when the agency fired her, then rehired her under a different Social Security number to avoid paying her for the vacation time she had earned.

"They don't want you to gain seniority," she said.

When Adriana started her cleaning job downtown, she said, the supervisor recorded her on the payroll under a different name. But rather than change the entry on ABM's payroll, he asked her to buy a set of documents with the new name — forcing her to live for years with two identities, one for work and one for everything else.

Adriana only managed to recover her real name by tagging it on as a middle name when Harvard took over the contract at her building and she reapplied for her job. Now, the name on her state ID is similar to the one on her Social Security card and paycheck.

Many get caught using bad Social Security numbers and lose their jobs. The Social Security Administration sends "no match" letters every year to about eight million workers and about 130,000 employers. Though the letter warns employers not to fire workers because of the mismatch, many do.

Lily, the Guatemalan immigrant, used to clean the offices of General Mills in suburban Minneapolis for a building contractor named Aramark. Earlier this year, she said, the company fired her and other workers, stating that it had received a letter from the government claiming the workers' Social Security numbers were wrong.

"They wanted to get rid of the people the supervisor didn't like," Lily said.

In a statement, Aramark said it "fully complies with federal laws and guidelines regarding employment eligibility, and has procedures in place to confirm employment eligibility of our employees. Should we discover that an employee does not have proper documentation, their employment with Aramark is terminated."

It added that it did not fire workers simply on receipt of a "no match" letter, but gave workers up to 90 days to fix the problem.

The one thing that illegal immigrants did not have to worry about, at least until recently, was the immigration police.

But life has been getting tougher. Minnesota, for instance, tightened its requirements to award state ID's or driver's licenses.

And, lately, immigration authorities have been pursuing illegal immigrants more aggressively. Since April, there have been high-profile raids at several work sites across the country, including IFCO Systems, a pallet and shipping container maker, where agents apprehended nearly 1,200 illegal workers and some managers.

Since Oct. 1, 2005, Immigration and Customs Enforcement has arrested more than 2,100 people in "work site enforcement investigations," compared with 1,145 for the entire previous fiscal year and 845 in fiscal 2004. It is also bringing more serious charges — such as harboring illegal immigrants and money-laundering of illicit profits — against employers who hire them.

Agents have also been sweeping through Minneapolis and other cities, seizing immigrants who had been served with deportation orders and expelling them from the country.

But immigrants adapt. Pablo Tapia, the leader of a church-based community group, has been holding tutorials for immigrants on how to avoid being deported. One rule is "don't open the door" if immigration authorities come knocking. Another is "stay calm and do not run" if agents raid the workplace.

"Just keep working," Mr. Tapia recommends. "If you run, it can be used against you in court."

Copyright 2006 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, National, of Monday, June 19, 2006

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |