| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

More Special Reports |

| Posted August 12, 2006 |

Help for the Hardest Part of Prison: Staying Out |

|

|

|

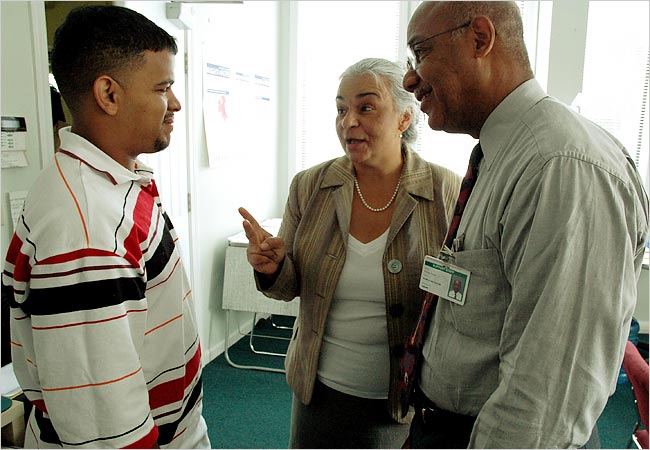

C.M. Glover for The New York Times |

|

| Alberto Reyes, left, who must find work to stay out of prison, sought help recently at the Family Life Center in Providence, R.I., where he talked with the center's director, Sol Rodriguez, and an employment specialist, William Scott. |

By ERIK ECKHOLM |

PROVIDENCE, R.I. — In April, Debra Harris took her 15-year-old son along for what she thought was a final visit to her parole officer. Instead, because of a “dirty urine” test two weeks before, proof of her relapse to crack use, state troopers led her straight back to prison for three more months.

Troopers then drove Ms. Harris’s son to the rented home on the south side of Providence where her boyfriend was suddenly left to tend to three of her children. Ms. Harris had forgotten to pay the gas bill, so service was cut and they lived through her sentence without a stove, surviving on fast food and microwave items.

Such jolting events are part of the fabric of life in South Providence, as some women and many more men cycle repeatedly through the state’s prisons. As the country confronts record and recurring incarcerations, the search for solutions is focusing increasingly on neighborhoods like it, fragile places in nearly every city where the churning of people through prison is intensely concentrated.

Rhode Island is among the states beginning to make progress in easing offenders’ re-entry to society with the goal of bringing the revolving door to a halt, or at least slowing it. But sometimes it can be hard to see much of a difference.

|

C.M. Glover for The New York Times |

| When one parent goes to prison, "the family structure disintegrated," says the Rev. Jeffrey A. Williams, a Providence preacher. |

The 1980’s and 90’s were an era of get-tough, no-frills punishment; inmate populations climbed to record levels while education and training withered. Prisoners with little chance of getting a job and histories of substance abuse were sent home without help.

Now a countertrend is gathering force, part of an unfolding transformation in the way the criminal justice system deals with repeat offenders. After punishment has been meted out and time has been served, political leaders, police officers, corrections officials, churches and community groups are working together to offer so-called re-entry programs, many modest in scope but remarkable nonetheless.

Inmates now meet with planners before their release to explore housing, drug treatment and job possibilities. Once the inmates are back outside, churches and community groups have been enlisted to take them by the hand and walk them through the transition home.

“What we’re witnessing is a great turning of the wheel in corrections policy,” said Ashbel T. Wall II, the Rhode Island corrections director.

The flood of more than 600,000 inmates emerging from the nation’s prisons each year, and the dismal fact that more than half of those will return, plays out relentlessly here, as elsewhere, keeping already troubled families in emotional and financial turmoil. Even with the new programs, the odds against staying straight are formidable.

“There’s a lot starting to happen,” said Sol Rodriguez, director of the Family Life Center, established in South Providence in 2003 to help returning prisoners and their families. “But this is still a very poor community, and people are coming back into already overburdened neighborhoods.”

In South Providence, where many families share aging two-story wood houses on deceptively quiet streets, nearly one in four male residents, and half of all black men, are under the supervision of the State Corrections Department — in prison, on parole or, by far the most common, on probation, Mr. Wall said.

Eight miles away, the state prison complex is an almost palpable presence. Of some 3,500 inmates released each year, one-fourth return to a core zone of South Providence of just 3.3 square miles with 39,000 residents, most of whom are Hispanic or black.

“One day somebody is just missing in action,” said Rev. Jeffery A. Williams, pastor of the 800-member Cathedral of Life Christian Assembly in South Providence. “The father gets a three- or five-year sentence, and the family structure disintegrates. Mothers try to survive on state aid or work multiple jobs, and you see kids practically raising themselves, which perpetuates the problem.”

The strains on families take many forms. Not far from the Harris household, Alberto Reyes, 27, a forklift operator, was put on probation last winter for burglary. But in March, Mr. Reyes failed to meet his parole officer and was sent to prison for three and a half months. Without his help, his girlfriend, who makes just $280 a week as a nurse’s aide, was left in desperate straits, he acknowledged, and had to rely on charity to get summer clothes for their baby.

|

C.M. Glover for The New York Times |

| Debra Harris with her grandson, recently prison but is not allowed to leave her home in Providence, R.I. |

The strains on families take many forms. Not far from the Harris household, Alberto Reyes, 27, a forklift operator, was put on probation last winter for burglary. But in March, Mr. Reyes failed to meet his parole officer and was sent to prison for three and a half months. Without his help, his girlfriend, who makes just $280 a week as a nurse’s aide, was left in desperate straits, he acknowledged, and had to rely on charity to get summer clothes for their baby.

Erick Betancourt, 26, spent 2 years in prison for dealing crack and will be on probation for the next 10 years, leaving him vulnerable to confinement for any mistake. “Everybody you bump into is on probation or parole,” said Mr. Betancourt, who has landed a job counseling youths in the streets.

“You’re not supposed to hang out with others on probation,” he said. “So you want to go back with your old friends, but that can be dangerous, because if the police stop you, that could be a violation.”

For Cerue Williams, 61, the repeated jailing of her 34-year-old son on drug and probation violations is causing financial burdens and social isolation. Laid off from her job engraving school rings, Ms. Williams is scraping by as she cares for her son’s teenage daughter.

Ms. Williams lives in a neat, rent-subsidized house, but she never talks with her neighbors. “I keep this inside, it’s embarrassing,” she said. “Nobody visits me, and I don’t visit nobody.”

|

C.M. Glover for The New York Times |

| Debra Harris leaving prison last month after serving extra time for a parole violation. |

South Providence is cut off from the city’s downtown and prosperous east side by an Interstate highway. Young men drive with their seats folded far back, their faces concealed behind the doorjamb — a fashion and a mock protective measure.

Parts of the area are gentrifying, and a Hispanic influx has brought small shops to the avenues. In abandoned jewelry factories, vacant lots and a few low-rise housing projects, roaming teenagers stir trouble with drugs, but the community’s woes are mostly hidden inside wooden multifamily homes.

Tyrone McKinney, 45, has been in prison 9 or 10 times since 1979 — he is not sure at this point — on charges ranging from shoplifting to attempted murder.

The last time Mr. McKinney was released, in January, he said, “they gave me a bus token, and I went out into the belly of the beast with no job, nowhere to go.”

Drifting through homes of South Providence, he resumed using drugs and stealing and was back in prison by April, for six months. He spoke in the prison gym, where he has bulked up over the years.

As a condition of his discharge this fall he must go into a residential drug treatment program, where he will also get help applying for benefits like food stamps and finding work and a longer-term home.

“The goal now is to see if you can rehabilitate lives instead of just locking them up,” said Gov. Donald L. Carcieri, a Republican, using words that once may have seemed politically risky. Mr. Carcieri has directed state agencies involved with education, drugs, mental health, housing and other issues to work with current and former prisoners.

Following an example set by Connecticut, Rhode Island has pledged to reinvest any savings from reduced prison populations in new aid for departing inmates.

Mayor David N. Cicilline of Providence has assembled a re-entry council, bringing together the police chief, religious leaders, businessmen and other community leaders. The council seeks to offer aid to every offender returning to the most affected neighborhoods, like South Providence.

In Washington, in another sign of the shifting national mood, the Second Chance Act, a bill to increase federal financing for re-entry programs, is moving through Congress with strong bipartisan support and the endorsement of the White House.

With its joining of public agencies and community groups, Rhode Island is part of a movement that is taking hold in dozens of states, said Debbie A. Mukamal, director of the Prisoner Reentry Institute at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York.

Yet in Rhode Island, as elsewhere, money and facilities, especially to support people once they return to the community, have not caught up with the new goals.

Inside the prison, offenders have more access to education, skills training and counseling. But many who are approved for parole must still spend extra months behind bars, waiting for drug treatment beds to open up. Those with no homes to return to face a severe shortage of transitional housing.

“Discharge planning doesn’t always mean a lot because there are still so few services out here,” said Ms. Rodriguez, of the Family Life Center.

Copyright 2006 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, National, of Saturday, August 12, 2006.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |