| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

More Special Reports |

| Posted July 25, 2007 |

Haiti Tastes Peace Under Preval |

|

The president who shies from the spotlight, nudges his traumatized nation slowly forward -- too slowly for some. |

|

Los Angeles Times |

| He seeks justice, but "recovery is very slow and time is against us," says a leading activist. |

traumatized nation slowly forward -- too slowly for some. By Carol J. Williams, Times Staff Writer July 25, 2007

By CAROL WILLIAMS, Times Staff Writer |

PORT-AU-PRINCE, HAITI — Shoeless boys with angry eyes and empty stomachs no longer loiter outside the green iron gates of the National Palace.

The odd jobs of oppression have disappeared. In the unfamiliar atmosphere of peace, there are no more orders to bash heads or crush dissent that once earned the ragtag enforcers a plate of rice and beans or a tube of glue to sniff.

A year into his second tenure as president, Rene Preval has broken ranks with two centuries of despots and demagogues.

Preval has eschewed the politics of brutality and confrontation, quietly achieving what only a year ago seemed unimaginable: fragile unity among this country's fractious classes.

Allies and adversaries alike credit the reclusive president with creating a breathing space for addressing the poverty and environmental devastation that have made Haiti the most wretched place in the Western Hemisphere. Preval has taken small steps to crack down on crime and corruption, and improve Haiti's infrastructure and food supply. But he largely holds fast to the strategy he used in defeating more than 30 rivals in the presidential race last year: Make no promises, raise no expectations.

Observers say Preval's low-key approach may be what Haiti has needed, but they worry what will happen if his shaky health takes a turn for the worse or if the country's 8 million people start to lose patience with his go-slow approach.

Preval loathes the limelight, evading ceremony and exuding moody impatience with meetings, limiting them to what aides insist are essential contacts to begin moving mountains of corruption, injustice, squalor and 70% unemployment.

He seldom leaves the palace, where visitors find him padding between his office and apartment in polo shirts and sandals. When he must go out, he travels in a modest motorcade without the customary sirens and outsize entourage.

A loner chafing in the midst of liveried staff and a protective contingent of U.N. soldiers, the president has been known to sneak out for a nocturnal stroll, incognito in the poorly lighted parks surrounding the palace.

His private life, by contrast, is more of an open book, at least in the gossipy circles of the business and political elite. The bourgeoisie in the elegant villas of Petionville were atwitter six months ago when Preval installed a new paramour at the palace, driving out his estranged-then-reconciled second wife, Geri.

A once-legendary consumer of the island's famed Barbancourt rum, Preval has lately cut down in favor of an occasional whiskey and decidedly fewer Marlboros. Some attribute the reining in of his excesses to a cancer scare over the winter, when doctors found signs suggesting a recurrence of the disease. He makes regular visits to Cuba for treatment, grouses about the side effects of his medications, but looks to be weathering the demands of office as well as can be expected of a 64-year-old long advised to make lifestyle changes.

Colleagues panic at the thought that the prostate cancer that was diagnosed and treated six years ago could recur and force him from office.

"It would be a catastrophe, the end of everything. We can't even permit ourselves to consider this possibility," one advisor said.

Those closest to Preval praise his modesty but sometimes despair of his reticence.

"Some people think he's too laid-back," conceded Lionel Delatour, a business consultant and friend. Preval hasn't made a single diplomatic appointment since taking office, Delatour said, shying from the kinds of decisions that could alienate factions in his broad coalition.

"He isn't going to make waves," Delatour said. "He told his ministers that he didn't want to see massive firings" of civil servants, as occurred after his mentor, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, fled following his ouster in February 2004 and a caretaker government swept his supporters from office.

Aristide basked in ceremony, donning his presidential sash with relish. In contrast, after 14 months in office, Preval has yet to tour the countryside, make a public address, give a news conference or grant an interview.

"He's a very low-key president, but it would be a mistake to think he's not a hands-on president," U.S. Ambassador Janet Sanderson said. Still, she wishes he would get out more and promote the hard-won stability he has secured to give confidence to potential tourists and investors.

Some point to Preval's 1996-2001 presidency, when he was perceived as doing Aristide's bidding, as the cause of his reluctance to trumpet recent successes.

"He's very cautious and low-key, perhaps because he was part of the mess," veteran human rights activist Jean-Claude Bajeux says of Preval, whom he considered too willing an accomplice of Aristide when the former priest was arming street gangs and repressing opponents.

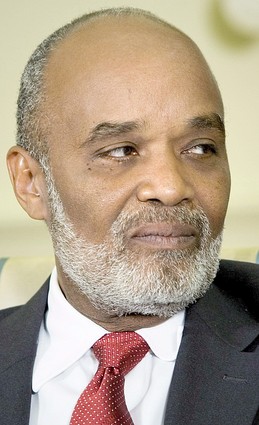

Haitian President Rene Preval click to enlargePreval, the son of a gentleman farmer and former agriculture minister, was educated in engineering and agronomy in Belgium in the 1960s, when leftist student movements set the political tone across Europe. His rural, but privileged, origins in Haiti and his foreign experience forged a politician who was initially "not just a populist but an anarchist," Bajeux said.

He believes Preval is now skillfully moving the country away from the disorder of populist revolution but without any recognizable governing model. That experiment could fail if the millions without work or much hope of it in the near future get restless, he said.

"Recovery is very slow, and time is against us," said Bajeux, 76. "There is misery now like never before. People are hungry, children's health is declining. People are not endlessly patient."

One reason Preval was drafted into running for president was his success in transforming the small town of his birth, Marmelade, into an island of agrarian prosperity. The town, in the lush northern Artibonite region, is planted with bamboo that locals harvest, fashion into furniture and market throughout the Caribbean. Profits from the cooperatives formed by Preval have been plowed into a community Internet center, public works and schools.

In office, Preval has confronted only the most egregious troublemakers. Kidnappings for ransom surged late last year, prompting him to authorize U.N. peacekeepers to target slum gang leaders. Two major criminal bosses were killed, a dozen jailed and any remaining kingpins have gone into hiding. Kidnappings fell from 42 in January to eight in June.

With the security situation improved, Preval turned to crimes of the elite: corruption and tax evasion. One of Haiti's wealthiest men, banker and mobile phone magnate Franck Cine, has been in the fetid penitentiary since mid-May pending trial on charges of expropriating deposits.

There are glimmers of improvement: Electrical generation plants are being repaired with foreign aid. A new road to the north is under construction. Food aid for orphanages and health centers is flowing. Flights from Miami, Fort Lauderdale and New York have tripled in the past year, bringing thousands who patronize hotels, restaurants and open-air markets selling paintings, voodoo flags and punched-metal sculptures.

A handful of new investments in the mobile phone and textile industries have created a few hundred new jobs but in a country needing millions.

The business elite and other former opponents praise Preval for those small steps to improve the economy, but that has gained him little capital on the squalid streets of Port-au-Prince, where two in five Haitians live. Most of them are jammed into one-room hovels, often next to open sewers and charred reminders of gang war.

The few complaints Haitians voice about their leader center on the achingly slow pace of change in their daily lives.

"We're living in a very delicate moment now," said Micha Gaillard, a professor who was a political opponent of Preval but now serves on his committee to reform the judiciary. "If there are no clear signs of improvement at the social level, everything he's done to combat insecurity and corruption could come to an explosive end."

Some of the poor say they are not impressed.

"If there's anything to be thankful for, God is responsible," sniffed Nadine Domaius, a 42-year-old mother of four who was selling soft drinks in the crush of rickety pushcarts, honking jalopies, smoke-belching trucks and women carrying heavy bundles on their heads.

Denis Sonel, another slum-dweller selling prepaid phone cards across from the National Palace, concedes it is now safe to walk the streets. But he, too, is reluctant to credit Preval.

Motioning with his head toward the palace, the 53-year-old father of five said: "Preval was already there once and he didn't do much."

Much of Preval's support among the poor stemmed from his association with Aristide, who vowed to seize the wealth of the nation from the few dozen families who control 90% of the economy.

Many of those who voted for him last year thought that if he were elected, he would bring Aristide back from exile.

"We voted for him, but he hasn't said anything about the return of Aristide, and the population is getting very angry about that," said Annette August, a militant supporter of Aristide's Lavalas movement.

For conservatives such as Daniel Fouchard at the other end of the spectrum, Preval is a strange political bedfellow but an effective leader.

Fouchard has been brought in to the Tourism Ministry to craft a plan to help eradicate poverty one household at a time by drawing local craftsmen, drivers, cooks and cleaners into restored community markets, eco-touring and rural hostels.

"Preval has opened the government to all," said the businessman, who backed a wealthy colleague in last year's election. "For the first time since the 19th century, we have no troublemakers at work. It's not a window of opportunity, it's a great big gate."

--

Copyright 2007 Los Angeles Times. Reprinted from The Los Angeles Times of Wednesday, July 25, 2007.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |