| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted March 2, 2003 |

| From Naoh's Curse to Slavery's Rationale |

|

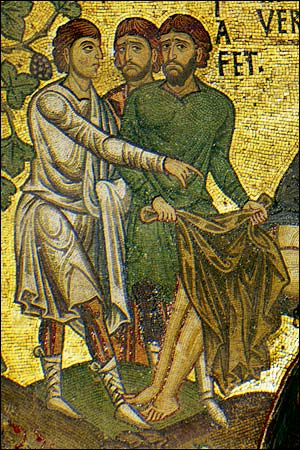

Erich Leasing/Art Resource, N.Y. |

| A mosaic of Noah being covered by his sons. |

| By FELICIA R. LEE |

A S stories go, this one has all the elements of good soap opera: nudity, sex and dysfunctional families. For many scholars, though, the enigmatic tale in Genesis 9 describing how Noah cursed the descendants of his son Ham with servitude remains a way to explore the complex origins of the concept of race: how and why did people begin to see themselves as racially divided?

In the biblical account, Noah and his family are not described in racial terms. But as the story echoed through the centuries and around the world, variously interpreted by Islamic, Christian and Jewish scholars, Ham came to be widely portrayed as black; blackness, servitude and the idea of racial hierarchy became inextricably linked.

By the 19th century, many historians agree, the belief that African-Americans were descendants of Ham was a primary justification for slavery among Southern Christians.

The debate about just what the story of Ham and Noah means has marched on into the 21st century. Today scholars are increasingly reading documents in the authors' original languages and going further back in time and to more places, as well as calling on disciplines like sociology and classics. Their ambitions are also bigger than just parsing Ham.

"What I've been trying to do for 40 years is move the emphasis of scholarship about slavery from a parochial emphasis to looking at early times," said David Brion Davis, the director of the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance and Abolition at Yale and a Pulitzer Prize-winning historian. That often means going to biblical or prebiblical sources and commentary, he said.

On Friday the center will begin a two-day conference on "slavery and the construction of race," in which the origins of the idea of race will be discussed.

"People are just going back and doing a lot more research, a lot more probing of sources," said George M. Fredrickson, the author of "Racism: A Short History" (Princeton University Press, 2002) and an emeritus professor of history at Stanford.

As for Ham, he said, "It's been a flexible curse — Jews, peasants, Tatars, have been considered cursed over the years."

David M. Goldenberg, a historian and a visiting scholar at the University of Pennsylvania, spent 13 years investigating every reference to blacks in Jewish literature up to about the seventh century. He is publishing the results of his research next month in "The Curse of Ham: Race and Slavery in Early Judaism, Christianity and Islam" (Princeton University Press). Among his surprising findings, he said, is evidence that a misreading of Hebrew and other Semitic languages led to the mistaken belief that the word "Ham" meant "dark, black or heat."

He concludes that in biblical and post-biblical Judaism there are no anti-black or racist sentiments, a finding that some scholars dispute. He also contends that the notion of black inferiority developed later, as blacks were enslaved across cultures. His findings, he said, dovetail with those of other scholars who have not found anti-black sentiment in ancient Greece, Rome or Arabia.

"The main methodological point of the book is to see the nexus between history and biblical interpretation," Mr. Goldenberg said. "Biblical interpretation is not static."

Stephen R. Haynes, a professor of religion at Rhodes College in Memphis, is less interested in the origins of Ham's supposed blackness than in why certain cultures have found the story so alluring.

"It appealed to racial slavery because Ham acted like you expected a black man to act," said Mr. Haynes, who published "Noah's Curse: The Biblical Justification of American Slavery" (Oxford University Press) last year. "Slavery was necessary in the white Southern mind to control the ungovernable black. Slavery is the response to Ham's rebellious behavior."

In the Bible, Ham finds Noah drunk and naked in Noah's tent. He tells his brothers, Shem and Japheth, who proceed to cover their father without gazing at him. When Noah finds out what happened, he curses Ham's son Canaan, saying he shall be "a servant of servants." Among the many questions attached to this tale are what Ham did wrong. Was it looking at his father or telling his brothers or some implied sexual transgression? And why was Canaan cursed for Ham's actions?

"The reason the text was so valued by 19th-century people was that it was about honor," Mr. Haynes said. "Ham acted dishonorably, and slavery was life without honor."

While thousands of people have tried to interpret Noah's curse, Mr. Haynes writes: "Scholars of history and religion alike have failed to comprehend that pro-slavery Southerners were drawn to Genesis 9:20-27 because it resonated with their deepest cultural values." Too often, he writes, historians have a superficial knowledge of the Bible, and scholars of religion have a limited knowledge of Southern culture.

Benjamin Braude, a professor of history at Boston College and co-director of its program in Middle Eastern and Islamic studies, argues that scholars are focusing on Ham and religious sources with wider lenses. He agrees with Mr. Goldenberg about the absence of racism in the ancient world and with his argument about the misinterpretation of rabbinic passages but disagrees with his assertion that there was no color-based identity in the ancient Near East or the Bible.

"In 18th- and 19th-century Euro-America, Genesis 9:18-27 became the curse of Ham, a foundation myth for collective degradation, conventionally trotted out as God's reason for condemning generations of dark-skinned peoples from Africa to slavery," says Mr. Braude's paper for the Yale conference. "In prior centuries, Jews, Christians and Muslims had exploited this story for other purposes, often tangential to the later peculiar preoccupation."

Like other scholars, Mr. Braude concludes that later social and economic forces turned Ham into a justification for slavery. "Before the 16th or 17th century, the racial interpretation of Ham is absent or contradictory," he said in an interview. "The clearest element is in Islamic culture, but even there it is contested and not universally accepted."

John O. Hunwick, a professor of history and religion at Northwestern University, agrees that an examination of slavery in Islam, a subject he thinks has been neglected, may hold some answers. He theorizes that because Ethiopians were the first group held as slaves in Arabia, blackness became associated with servitude.

One of the pitfalls in answering questions about race is finger-pointing, said Werner Sollors, a professor of English and African-American studies at Harvard, who has written widely about race, including the curse of Ham.

"The question is: where does this thing we call racism or racial hierarchy start, and it's been very contentious," he said. "It's a huge question and has a big blame attached to it. Is it the Christians, the Muslims or the Jews? You find evidence for all three."

While the questions are not new, serious academic attention to blacks in antiquity began only in the 1960's, with books by Frank J. Snowden, a classics professor at Howard University, which is historically black, Mr. Sollors said.

And now, Mr. Braude said, "a lot of people are pushing the questions about race much further in time and reinterpreting texts that have been misunderstood from the Renaissance onward."

"This society is obsessed with race and color," he continued. "There is, in fact, in the academy a commitment to understanding the social construction of race, but we don't look at the construction site. We are trying to see the elements that go into this — to pull them apart and to see what fits and doesn't fit."

Copyright 2003 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Arts & Ides, of November 1, 2003.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |