| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted January 12, 2004 |

|

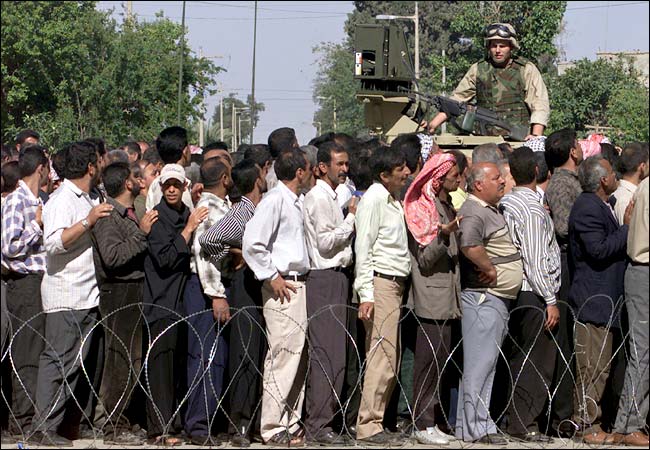

Tyler Hicks/New York Times |

| An economy shattered. An American soldier disperses Iraqis after an explosion at a gas station. |

| Free-market Iraq? Not So Fast |

BY DAPHNE EVIATAR |

There is no doubt about American intentions for the Iraqi economy. As Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld has said, "Market systems will be favored, not Stalinist command systems."

And so the American-led coalition has fired off a series of new laws meant to transform the economy. Tariffs were suspended, a new banking code was adopted, a 15 percent cap was placed on all future taxes, and the once heavily guarded doors to foreign investment in Iraq were thrown open.

In a stroke, L. Paul Bremer III, who heads the Coalition Provisional Authority, wiped out longstanding Iraqi laws that restricted foreigners' ability to own property and invest in Iraqi businesses. The rule, known as Order 39, allows foreign investors to own Iraqi companies fully with no requirements for reinvesting profits back into the country, something that had previously been restricted by the Iraqi constitution to citizens of Arab countries.

| _______________________ |

American plans for overhauling the economy may violate treaties. |

| _______________________ |

In addition, the authority announced plans last fall to sell about 150 of the nearly 200 state-owned enterprises in Iraq, ranging from sulfur mining and pharmaceutical companies to the Iraqi national airline.

But the wholesale changes are unexpectedly opening up a murky area of international law, prompting thorny new questions about what occupiers should and should not be permitted to do. While potential investors have applauded the new rules for helping rebuild the Iraqi economy, legal scholars are concerned that the United States may be violating longstanding international laws governing military occupation.

History provides limited guidance. The United States signed both the Hague Regulations of 1907 and the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949 and has incorporated their mandates regarding occupation into the Army field manual "The Law of Land Warfare." But foreign armies, whether the Vietnamese in Cambodia, the Turks in Northern Cyprus or the United States in Panama and Haiti, have rarely declared themselves to be occupying forces. After World War II, for example, the Allies claimed the Hague regulations did not apply because they had sovereign power in Germany and Japan, which had surrendered. And although most of the world calls Israel's control of the West Bank and Gaza since 1967 an occupation, the Israeli government has not accepted that status, although it has said it will abide by occupation law.

|

Reuters |

| A G.I. watches oil workers lining up for their pay. |

Reconstruction and privatization in Kosovo, for example, have been bitterly debated. The United Nations authority over Kosovo, set up by the peace treaty after a war that was unsanctioned by the United Nations, hesitated to privatize what was in essence seized state property, but it decided the economic future of Kosovo was too important to wait for a final peace settlement that would fix Kosovo's legal status.

The government in Belgrade and the much-reduced Serbian community in Kosovo have argued that such sales are specifically forbidden in the United Nations resolution setting up the authority itself. This dispute, though similar, sidesteps questions of occupation law because Kosovo, unlike Iraq, involves United Nations and NATO forces.

In Iraq the latest pronouncements by the Security Council only add to the muddle. Resolution 1483, issued in May, explicitly instructs the occupying powers to follow the Hague Regulations and the Geneva Convention, but in a strange twist it also suggests that the coalition should play an active role in administration and reconstruction, which many scholars say violates those treaties.

| _______________ |

| Old occupation law doesn't seem to fit modern warfare. |

| _______________ |

The conflict centers on Article 43 of the Hague Regulations, which says an occupying power must "re-establish and insure, as far as possible, public order and safety, while respecting, unless absolutely prevented, the laws in force in the country."

In other words, the occupying power is like a temporary guardian. It is supposed to restore order and protect the population but still apply the laws in place when it arrived, unless those laws threaten security or conflict with other international laws.

"Under the traditional law the local law should be kept unchanged as much as possible," said Eyal Benvenisti, professor of international law at Tel Aviv University and author of "The International Law of Occupation" (Princeton, 1993). Repairing roads, factories and telephone systems, then, is a legitimate way to get the economy running again. But transforming a tightly restricted, centrally planned economy into a free-market one may not be.

In a memo written last March and leaked in May to The New Statesman, the British magazine, Lord Goldsmith, Prime Minister Tony Blair's top legal adviser, warned that "the imposition of major structural economic reforms" might violate international law, unless the Security Council specifically authorized it.

Officials of the coalition authority insist the Security Council did that with Resolution 1483. They maintain that wiping out Saddam Hussein's entire economic system falls within Resolution 1483's instructions "to promote the welfare of the Iraqi people through the effective administration of the territory" and assist the "economic reconstruction and the conditions for sustainable development."

So the authority is pressing ahead with most of the plans for economic reform in Iraq and promises to have new laws in Iraq governing, among other things, business ownership, foreign investment, banking, the stock exchange, trade and taxes by June, when power is to be transferred to the Iraqis.

"We believe the C.P.A. can undertake significant economic measures in Iraq particularly where those measures support coalition objectives and the security of coalition forces," said Scott Castle, general counsel to the coalition. "There's a close nexus between the economic health of Iraq and the security of Iraq."

Some experts in international law call that a stretch. "The Security Council cannot require you to comply with occupation law on one hand and on the other give you authority to run the country in defiance of that law," said David Scheffer, a professor of international law at Georgetown University and a former United States ambassador at large for war crimes issues. He added that "1483 is internally inconsistent."

Order 39 "raises the biggest single question about coalition policy as it relates to the laws of war," said Adam Roberts, a professor of international relations at Oxford University and an editor of "Documents on the Laws of War" (Oxford, 2000). "That order embodies a major change not just in human rights or the political situation, but in the economic one. It would appear to go further in a free market direction and in allowing external economic activity in Iraq than what one would expect under the provisions of the 1907 Hague law about occupations."

International business lawyers at a conference of investors in London in October similarly warned that the coalition authority's orders might not be legal.

Part of the problem is that the old occupation law does not seem to fit the realities of modern warfare. As Mr. Benvenisti explains in his book and in a forthcoming article in the Israel Defense Forces law review, when the Hague regulations were initially drafted, war was understood to be a legitimate contest between professional armies, not a messy attempt to remove a tyrannical leader.

"The Hague law reflects the interests of sovereigns to maintain their basis of power, their property and their institutions," Mr. Benvenisti said. Instead of wholesale transformation of a nation, then, occupation was supposed to be a short, transient state of affairs, with minimal intervention of the occupying authority in the lives of civilians.

But in Iraq the United States' explicit goal is to completely remake Iraqi institutions and society. "Their objectives far exceed the constraints of the law," Mr. Scheffer said, noting that occupation laws were restrictive precisely in order to prevent overzealousness on the part of an occupying power. "We're squeezing transformation into a very tight square box called occupation law, and the two really are not a good match."

In a forthcoming article in the American Journal of International Law, he sets forth a dozen possible violations by the occupying powers of international law, including failure to plan for and prevent the looting of hospitals, museums, schools, power plants, nuclear facilities, government buildings and other infrastructure; failure to maintain public order and safety during the early months of the occupation; and excessive civilian casualties.

In the article Mr. Scheffer explains how individuals could use United States laws to sue individual coalition officials in American courts. "This is a rather uncharted field in U.S. jurisprudence," he said in an interview. "But I would not underestimate how far litigation might go."

Ruth Wedgwood, a professor of international law at Johns Hopkins University and a member of the Defense Policy Board, which advises the Pentagon, is not so concerned. In her view the Iraqi laws do not deserve much deference because they were issued by an authoritarian government. "If it's not a democratically crafted law, it lacks the same legitimacy," she said.

Coalition officials have recently backtracked on privatization, in part because of the legal concerns. "We recognize that any process for privatizing state-owned enterprises in Iraq ultimately must be developed, adopted, supported and implemented by the Iraqi people," Mr. Castle said.

Still, some specialists worry that the radical economic changes that are moving forward will lack legitimacy in the eyes of Iraqi citizens. Iraqis may see such wholesale economic transformation as "threatening and potentially exploitative," said Samer Shehata, professor of Arab politics at Georgetown University. "I think the sensible answer is to leave extremely important decisions like the possibility of complete foreign ownership of firms to a later date, when a legitimate Iraqi government is elected by the Iraqi people in free and fair elections."

Copyright 2004 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Arts & Ideas, of Saturday, January 10, 2004.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |