| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

More Special Reports |

| Posted February 22, 2006 |

|

Photographs Eustacio Humphrey for The New York Times |

| The 17 percent foreclosure rate in Cuyahoga County, Ohio, is creating blight in many neighborghoods, including Slavic Village, where about 500 homes are vacant. |

| For Many Minorities, Signs of Trouble in Foreclosures |

BY VIKAS BAJAJ |

and RON NIXON |

CLEVELAND — Catrina V. Roberts, a single mother of four, joined a new, growing class of minority homeowners when she moved from her subsidized apartment to a two-story house in 1999.

But Ms. Roberts fell behind on her payments and declared bankruptcy last year. Now, as she loses her modest home to foreclosures, Ms. Roberts may represent the vanguard of a worrying trend of retreat.

The housing boom of the last decade helped push minority home ownership rates above 50 percent for the first time in 2004 and the overall foreclosure rate below 1 percent. Social scientists laud these accomplishments because ownership can foster greater neighborhood stability and economic progress. President Bush cites rising minority ownership as a milestone achievement under his "ownership society" programs.

But hidden behind such success stories lies a disturbing trend: in the last several years, neighborhoods with large poor and minority populations in places like Cleveland, Chicago, Philadelphia and Atlanta have experienced a sharp rise in foreclosures, in some cases more than a doubling, according to an analysis of court filings and other housing data by The New York Times and academic researchers.

The black home ownership rate even dipped slightly last year, according to the Census Bureau.

The increase in foreclosures could be the first of a wave of financial distress for many minority homeowners, experts say, because they are twice as likely as whites to have taken out expensive subprime mortgages, most of which will jump to higher interest rates in the next two years, according to an analysis of data that lenders disclose under the federal Home Mortgage Disclosure Act.

Subprime loans, which are made to borrowers with credit histories that the industry considers less than prime, have interest rates that are, on average, three points higher than the prime rate, about 6.2 percent now, and they carry higher fees and prepayment penalties that make it expensive to refinance.

Some housing experts worry that the minority foreclosure rate could worsen if the economy or the housing market, nationally or regionally, hits a rough patch as it has in industrial Midwestern states like Ohio.

"Anybody who is on the edge, those are factors that can tip them over into foreclosure," said William C. Apgar, a lecturer at Harvard who has studied foreclosure patterns in Atlanta, Chicago and Los Angeles. "That could happen even though foreclosure rates are down."

The example of Ms. Roberts is noteworthy because her loan was not considered subprime. It came from KeyBank, a longstanding Cleveland institution, and carried a relatively low fixed interest rate of 7.4 percent on a principal of $65,000. She never had a credit card, much less a credit record, and put down only $2,000.

Over the years, Ms. Roberts's monthly expenses rose because of repairs to a dilapidated porch and the birth of two grandchildren, but the $880 a month she takes home after taxes from her job as a home health aide did not.

Ms. Roberts, 35, also receives $1,100 in Social Security benefits because two of her younger children have learning disabilities. "I know when you buy a house, eventually you have to put work into it," she said and sighed, "but I didn't know it would lead me here, because if I did I would have never bought it. So, I am at a point right now that I don't want to ever buy a house, ever again."

|

| Catrina Roberts, left, with her daughter Sanautica, 12, and granddaughter Neaskia, 4. Ms. Roberts's home in Cleavand is in foreclosure and she has declared bankruptcy. |

The Mortgage Bankers Association of America plays down the severity of foreclosures, noting that most new minority homeowners are doing well and that the Midwest is facing unique economic challenges. The trade group estimates that fewer than 1 percent of all loans were in foreclosure in the three months that ended last September, down from 1.5 percent in 2002. For subprime loans, the rate was 3.3 percent, down from 8 percent in 2002.

| Trouble in Cuyahoga County |

But broad national statistics can obscure hard local realities. In Cuyahoga County, which includes Cleveland, Ms. Roberts's hometown, court filings by lenders seeking to foreclose on delinquent borrowers totaled more than 11,000 in 2005, more than triple the number in 1995.

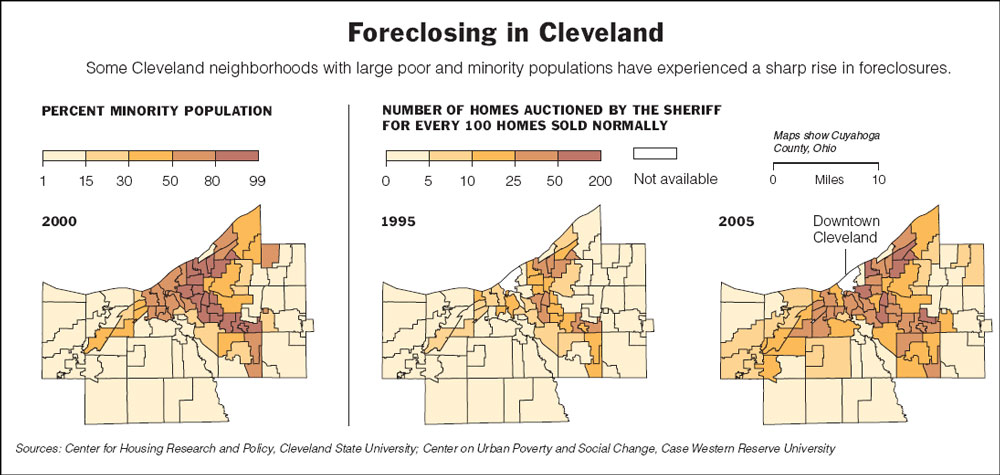

There were 17 auctions of foreclosed properties for every 100 regular single-family homes sold in the county in 2005, up from 10 in 2004 and 5 in 1995, according to data tabulated by Cleveland State University. (Not all homes that enter foreclosure are sold at auction; sometimes borrowers and lenders settle out of court or the property is sold on the open market.)

There is no way to know how many foreclosures of minority-owned homes have occurred in the Cleveland area, because county filings do not identify people by race. Experts say the closest proxy is the number of auctions of seized homes conducted by a sheriff as a ratio of conventional sales in areas with large minority populations.

In the eastern part of the county, which is 52 percent black and 7 percent Hispanic, the ratio of auctions to regular sales was 23 per 100 last year, up from 9 in 1995. In the west, which is 82 percent white, the ratio was 11 per 100, up from 2.5.

A similar pattern can be seen in Chicago, where foreclosure filings tripled, to 7,576, from 1993 to 2005. Neighborhoods where the population is more than 80 percent non-white account for 65 percent of all cases, up from 61 percent in 1993, according to data compiled by the National Training and Information Center, a housing advocacy and research group based in Chicago. The same trends have been documented in Atlanta and Philadelphia, according to researchers from Harvard and the Reinvestment Fund, a Philadelphia-based investment organization hired by the Pennsylvania Department of Banking to study mortgage foreclosures in the state.

Mr. Apgar and other experts note that foreclosure is the worst, but not the only, negative consequence faced by overextended minority families.

In areas where home prices have appreciated, families that have defaulted on their loan might still be able to sell their homes before they are seized. Though they would lose their homes and damage their credit records, their financial troubles would not register in foreclosure statistics. People who live in the great middle of the country where home prices have not risen rapidly may not have that option because demand there is soft.

At stake are historic gains in minority home ownership rates, which until the mid-1990's had been stagnant for two decades.

Last year, black home ownership fell slightly, to 48.8 percent, from 49.7 percent in 2004, only the second year the rate has declined in the last 10 years. Still, the fact that nearly half of all black households and half of all Hispanic families owned their homes is widely seen as a step forward.

In 1995, fewer than 43 percent of black families and just under 44 percent of Hispanic families owned their own homes. Among all minorities, a group that includes Asians and mixed-race households, the rate was 51 percent in 2005, up from 44 percent a decade ago. By comparison, more than three-quarters of white households owned their own homes in 2005, up from 71 percent.

| The Role of Subprime Loans |

In addition to lowering crime and revitalizing blighted neighborhoods, home ownership also helps families build wealth that can pay for education and be passed on to the next generation, said Dowell Myers, a professor at the University of Southern California who has studied Hispanic home buying patterns.

Experts attribute the recent increase in minority ownership to income and employment gains, but also to the growth of subprime lending, which provides credit in areas where few lenders and banks operated before. The expansion of credit, particularly to the poorest minorities, has been controversial.

Advocates for the poor say that aggressive lenders and mortgage brokers have given loans to borrowers who are lured by dreams of home ownership but have few savings and little job security. Many families might be better off, and receive less expensive loans, if they saved for a down payment and paid down other debts before buying a home, said Kathleen E. Keest, a senior policy counsel at the Center for Responsible Lending, a housing advocacy and research group based in Durham, N.C.

And for all the talk of expanding opportunities to the less well-off, experts note that the gap between minority and white home ownership remains unchanged from a decade ago at about 25 percentage points.

Loan data that mortgage lenders must disclose show that minorities are far more likely to receive subprime loans than whites. About 30 percent of home purchase loans made to blacks from 1999 to 2004 and 20 percent of home loans made to Hispanics were subprime, compared with 10.4 percent of loans to Asian-Americans, only slightly higher than for white borrowers.

In 2004, the latest year with data available, nearly 27 percent of loans taken out by minorities were subprime, up from 15 percent in 1999.

The disparities persist even when income is taken into account. Among minority borrowers who made $51,000 to $75,000 a year, 23 percent received subprime loans. By comparison, only 10 percent of whites in the same income bracket did. Minorities who made $151,000 to $175,000 were twice as likely to get a subprime loan as whites were.

|

The New York Times |

The Mortgage Bankers Association said lenders used a number of factors like credit scores and the size of down payments, in addition to income, to determine what kind of loan and interest rates are offered to borrowers. For instance, "whites have traditionally had more wealth than minorities, and that's a factor in who gets what kind of loan, as well," said Douglas G. Duncan, the chief economist at the trade group.

Almost 70 percent of subprime loans issued since 2001 will shift from low, fixed introductory rates to higher adjustable rates in the next two years, according to an analysis by Fannie Mae.

Still, Mr. Duncan added, subprime lending has benefited minorities and lower-income borrowers. For every 100 subprime loans made nationally, only 5 end in foreclosure. Some increase in total foreclosures is to be expected simply because the number of mortgages has increased substantially over the last decade, he said.

Mr. Duncan and others in the industry say that higher foreclosure levels in the Midwest should not be seen as worrying signals for the nation because the region's economic problems are unique.

Ohio lost 215,000 jobs from 2001 to 2005, with 63,800 of them coming from the Cleveland metropolitan area. The state unemployment rate was 5.6 percent in December, up from 4 percent in 2000. The jobless rate in Cleveland was 5.5 percent in December, up from 3.8 percent.

James Rokakis, the Cuyahoga County treasurer and an advocate of tighter lending standards, said a 5 percent national foreclosure rate for subprime loans was acceptable to lenders because their profits were greater on those loans than on prime mortgages. But he noted that his county's 17 percent rate is creating blight in many neighborhoods.

In Slavic Village, once a thriving Eastern European enclave where many of Cleveland's steelworkers lived and now an increasingly black and Hispanic neighborhood, about 500 homes, or 5 percent of its properties, are vacant, Mr. Rokakis said. "Who pays for the damage done to these communities?"

Vikas Bajaj reported from Cleveland for this article and Ron Nixon from New York.

Copyright 2006 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Business, of Wednesday, February 22, 2006.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |