It is no surprise that the deaths of celebrities, like Michael Jackson, or honored political figures, like the United States diplomat Richard Holbrooke, are promoted as international Web events. So, too, was the memorial service for the six people killed Jan. 8 in Tucson, which had thousands of viewers on the Web.

|

|

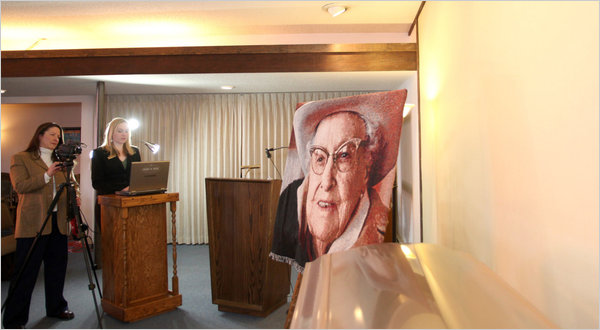

JAMIE OSBORNE FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES |

| Editing a Webcast at Dahl Funeral Chapel in Montana. |

But now the once-private funerals and memorials of less-noted citizens are also going online.

Several software companies have created easy-to-use programs to help funeral homes cater to bereaved families. FuneralOne a one-stop shop for online memorials that is based in St. Clair, Mich., has seen the number of funeral homes offering Webcasts increase to 1,053 in 2010, from 126 in 2008 (it also sells digital tribute DVDs).

During that same period, Event by Wire, a competitor in Half Moon Bay, Calif., watched the number of funeral homes live-streaming services jump to 300 from 80. And this month, the Service Corporation International in Houston, which owns 2,000 funeral homes and cemeteries, including the venerable Frank E. Campbell funeral chapel on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, said it was conducting a pilot Webcasting program at 16 of its funeral homes.

Traveling to funerals was once an important family rite, but with greater secularity and a mobile population increasingly disconnected from original hometowns, watching a funeral online can seem better than not going to a funeral at all. Social media, too, have redrawn the communal barriers of what is acceptable when relating to parents, siblings, friends and acquaintances.

“We are in a YouTube society now,” said H. Joseph Joachim IV, founder of FuneralOne. “People are living more than ever online, and this reflects that.”

Some of the Web-streamed funerals reflect the large followings gathered by individuals. On Jan. 11, more than 7,000 people watched the Santa Ana, Calif., funeral of Debbie Friedman, an iconic singer whose music combined Jewish text with folk rhythm. It was seen on Ustream, a Web video service, with more than 20,000 viewing it on-demand in the days that followed.

“We intended to watch a few minutes, but ended up watching almost the whole thing,” said Noa Kushner, a rabbi in San Anselmo, Calif., and a fan of Ms. Friedman’s music, who watched the service with a friend at his office. “I was so moved.”

After Stefanie Spielman, a breast cancer activist and the wife of the popular National Football League player Chris Spielman, died in 2009, the Spielmans wanted a private ceremony attended by 900 friends and family members, said Lajos Szabo, the chief strategy officer at Schoedinger Funeral and Cremation Service in Columbus, Ohio, which arranged the funeral. But they also hoped to accommodate members of the public, who wanted to support the family in its grief. Streamed live and posted online, Ms. Spielman’s funeral has been viewed 4,663 times by 2,989 visitors since November 2009, according to FuneralOne.

Other Webcasts are more obscure, but no less appreciated. Two weeks ago, a friend of Ronald Rich, a volunteer firefighter in Wallace, N.C., died unexpectedly. When Mr. Rich called the mother of his friend to say he could not make the eight-hour drive to the funeral because a snowstorm threatened to close roads, he said the mother offered to send an e-mail invitation so he could watch the service online. Mr. Rich said he watched the funeral: first by himself and a second time with his girlfriend.

“It was comforting to me,” he said, adding that he planned to watch it again with fellow firefighters.

The technology to put funerals online has been around for a decade but was slow to catch on with an industry understandably sensitive to questions of etiquette. Some funeral directors eschew streaming funerals live because they do not want to replace a communal human experience with a solitary digital one, said John Reed, a past president of the National Funeral Directors Association. Other funeral directors worry that if the quality of the video is poor, it will reflect badly on the funeral home.

And the conversation about whether to stream a funeral online can be awkward, particularly if a grief-stricken family is wary of technology. Funeral directors are conservative, Mr. Reed said; privacy, even for the Facebook generation, is paramount. “We don’t jump on the first thing that comes along,” he said.

Still, some funeral directors offer the service for free (Mr. Reed is one of them) while others charge $100 to $300. If a family wants to keep the online service private, those invited get a password that allows access. (Mr. Joachim said 94 percent of the funerals his company Webcast were not password-protected.)

Not all real-life funeral attendees want their images captured online. Irene Dahl, an owner of Dahl Funeral Chapel in Bozeman, Mont., said a young man went to a funeral last year dressed as a woman and asked not to be filmed. “He did not want his mother to know,” Ms. Dahl said. “So we did not face the camera in his direction.”

Ms. Dahl said that nearly one-third of the ceremonies arranged by her funeral home last year — about 60 — were streamed live, at no extra charge. She became interested in this option after Dan Grumley, the chief executive of Event by Wire, visited her in 2008 and showed her how it worked.

“Being a funeral director is about helping people with their grief,” she said.

Russell Witek, the 14-year-old son of Karen Witek of Geneva, Ill., died of a brain tumor in 2009. The Conley Funeral Home in Elburn, Ill., offered to stream the funeral live to friends and family members. “We said, ‘Why not?’ ” Ms. Witek said. Her brother-in-law was working in the Middle East and could not attend. Russell’s home health nurse was out of town. “It was spring break,” Ms. Witek said.

She had met a number of friends on social media sites, including a patient-care support group and another for parents who home-schooled their children, and they could not attend, either. “I wanted them to experience it,” Ms. Witek said.

According to Conley Funeral Home, 186 people watched the funeral live on April 3, 2009, with an additional 511 watching it on-demand through Jan. 15.

Ms. Witek said her husband had watched the funeral more than once, “because he wanted to hear what was said that day,” but said she couldn’t bring herself to view it, except in parts. “After a child dies, you go into a fog.”

But for William Uzenski, the father of Nicholas Uzenski, a Marine serving in Afghanistan who was killed on Jan. 11, 2010, live Web-streaming has provided much comfort. Mr. Uzenski’s body was transported to his home, Bozeman, 10 days later. William Uzenski, himself a former Marine, said he wanted Nicholas’s military colleagues in Afghanistan to be able to watch the funeral. So Ms. Dahl arranged it through a military liaison who was assisting the family.

Ms. Dahl said that, unlike many streamed funerals, Nicholas Uzenski’s had three separate Webcasts and was invitation-only. The Webcasts included the arrival of his coffin at a local airport, the funeral and a graveside ceremony that his family said included a 21-gun salute. Ms. Dahl tracked virtual attendees. The funeral and the graveside ceremony were watched by 124 and 39 people, respectively, with the funeral viewed in 80 cities and 4 countries, including Afghanistan.

“Some e-mailed me,” Mr. Uzenski said. “Friends thanked us for sharing it with them. I do watch it again sometimes. I don’t know why, but I guess it’s healing.”