| Want to send this page or a link to a

friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

Exile's Life

Unravels After Illegal Vote |

|

|

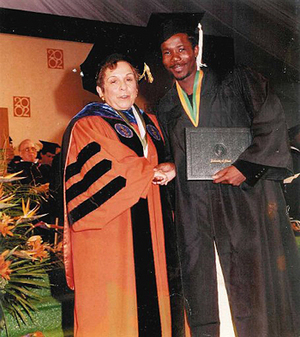

| In January 2002, a federal grand jury indicted Vandamme Jeanty on charges

of voting illegally, possessing a false Florida birth certificate and fraudulent Social

Security number to procure federal student loans. In May 2002, he was able to participae

in a University of Miami graduation ceremony. He is shown here with UM President Donna

Shalala. (Miami Herald Photo) |

Scion of a once-prominent family in Haiti, Vandamme Jeanty blossomed in exile.

He graduated with honors from North Miami Senior High School and enrolled in Miami-Dade

Community College, where his almost-perfect grade-point average was enough to place him

among six South Florida students considered for the inaugural class of Gates Millennium

Scholars eligible for full college scholarships.

Studying public administration, policy and law at the University of Miami, he seemed to

have a bright future.

But Jeanty's dreams collapsed when federal authorities discovered he was not a U.S.

citizen when he voted in the 2000 presidential election and had been arrested for

resisting officers.

He was convicted of illegally voting and two other separate charges and was ordered

deported after skipping his immigration hearing. But instead of hiding from immigration

authorities, like thousands of other undocumented immigrants, Jeanty turned himself in at

the Krome detention center in West Miami-Dade, where he is now being held.

Jeanty, 29, is yet another example of stepped-up immigration enforcement. A recent

report by Human Rights Watch said that from 1997 to 2005, 672,593 immigrants with criminal

records were deported -- the result of tougher immigration laws passed in 1996 that

require deportation of foreign nationals convicted of aggravated felonies.

Jeanty said he had good reasons for the transgressions: He grew up thinking he was a

naturalized U.S. citizen; and his father was killed in Haiti on the eve of Jeanty's

removal hearing.

Now Jeanty faces further scrutiny after filing a complaint against a detention officer

who Jeanty says used excessive force when Jeanty failed to move fast enough for a medical

checkup at the Krome clinic.

Immigration officials would not comment on Jeanty's allegations. But Iván Ortíz, a

spokesman for U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, said all abuse allegations are

investigated.

An agency official familiar with the case who did not want to be identified by name

because of privacy policies for detainees said Jeanty deliberately injured himself to

prevent transfer to another holding facility or to thwart deportation.

''ICE records show that every time Mr. Jeanty has been scheduled for a transfer or

removal, he has caused injury to himself to avoid being moved,'' the official said.

``There's documention indicating that he intentionally banged his head repeatedly against

the glass in the Krome processing area to cause a self-induced epileptic seizure. . . .

Another instance occurred when he was being scheduled for [a deportation] flight and he

climbed onto a bed and violently threw himself backwards onto the floor.''

Jeanty's extraordinary story begins in Haiti, where he says his father, Pierre Jeanty,

served in the security detail of Haitian dictator Jean Claude ''Baby Doc'' Duvalier.

Jeanty was 8 when his parents left Haiti after the 1986 collapse of the Duvalier

dictatorship.

He overcame language and cultural barriers and succeeded in school. An article in The

Miami Herald on Oct. 29, 2000, celebrated Jeanty and five other Gates Millennium Scholar

candidates. A foundation spokesman said Jeanty did not figure in the final lineup for a

scholarship.

The mistake that ultimately cost Jeanty his dreams came less than two weeks after the

article appeared.

On Nov. 7, 2000, he accompanied his mother to the polls and voted for Al Gore.

''I grew up thinking all along that I was an American,'' Jeanty said in one of several

telephone calls from Krome. ``It didn't occur to me at the time that I was breaking the

law. In fact, my mother had become a citizen, and I thought I was a citizen, too.''

However, when his mother became a citizen in the late 1990s, Jeanty was already an

adult and, by law, should have applied on his own for residency and then for citizenship.

But he didn't even have a green card, records show.

After the vote, Jeanty enrolled at the University of Miami.

By then, he was the father of a 3-year-old boy. He never married the boy's mother, who

cares for their son in Miami.

The first hint of trouble came when federal agents came to talk to Jeanty in early

2002, he recalled.

They asked about the vote and had a long list of other charges and allegations,

including use of 143 aliases, false statements while illegally applying for a passport and

several arrests for resisting officers dating back to 1997.

A U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement official familiar with the case said Jeanty

ultimately had three convictions on his record, including the illegal vote, resisting an

officer and loitering and prowling.

In January 2002, a federal grand jury indicted Jeanty on charges of voting illegally,

possessing a false Florida birth certificate and fraudulent Social Security number to

procure federal student loans.

He was arrested Jan. 25, 2002, but was released on bail and participated in a UM

graduation ceremony May 10. There is a photograph of him shaking hands with UM President

Donna Shalala, though he has yet to earn a degree.

UM students who expect to complete course work later in the year can take part in early

ceremonies, officials said.

Thirteen days after the ceremony, Jeanty appeared before U.S. District Judge K. Michael

Moore and pleaded guilty to one count of unlawfully voting in a national election. Under

the plea agreement, the other charges were dropped.

He gave the court a written apology for voting. ''I am sorry for my behavior, and I

accept full responsibility for my actions,'' he wrote.

Three months later, Moore sentenced Jeanty to three years of probation.

Jeanty then went to work as a paralegal specializing in immigration and labor law. But

trouble followed him.

Seven months before completing the sentence in 2005, Jeanty was back in federal court,

accused of violating his probation.

Federal court records show he was arrested in 2004 in Broward County for carrying a

concealed firearm, loitering and prowling. Jeanty said it was a case of mistaken identity.

The court withheld adjudication in that case. But because an arrest had occurred, Judge

Moore revoked Jeanty's probation and sentenced him to one year in prison.

Immigration officers detained Jeanty when he was released from federal prison in

Atlanta, but he posted bail and remained free pending a deportation hearing in Atlanta on

March 22.

He didn't show up, and a judge ordered him deported.

Jeanty says he was in North Miami consoling his family because his father, who had

returned to Haiti in 2006, had been abducted and killed on March 20 by kidnappers in

Port-au-Prince.

''That's why I missed my court date,'' Jeanty said. ``It was an emergency.''

Officials in Haiti were not able to confirm the elder Jeanty's death.

On June 16, Jeanty showed up at the Krome guardhouse to surrender. ''I turned myself in

because I wanted to fight the case legally,'' he said.

At Krome, Jeanty has had several run-ins with guards, and in September filed a

complaint alleging violence and claiming a guard called him a ``piece of Haitian

garbage.''

One of the officers ''violently snatched me by the collar, twirled me round and

violently twisted my arm into a lock to the point where my head was sandwiched between

both of my hands,'' Jeanty wrote in the typewritten complaint to the U.S. Department of

Justice.

Ortíz said Jeanty's complaint was being reviewed. ``We take allegations of misconduct

against ICE employees very seriously.''

As Jeanty waits at Krome, his mother worries about his pending deportation.

''I don't know what's going to happen to him,'' said Marie Rose Jeanty, who lives in

Miami. ``He could suffer the same fate as his father. I'm so worried.''

Copyright 1996-2007 The Miami Herald Media Company. Reprinted from The Miami Herald of

Wednesday, November 7, 2007.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of

democracy and human rights |