| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| More Books and Arts |

| Posted December 28, 2008 |

| Early American Echoes in South Africa? | |

|

|

|

|

|

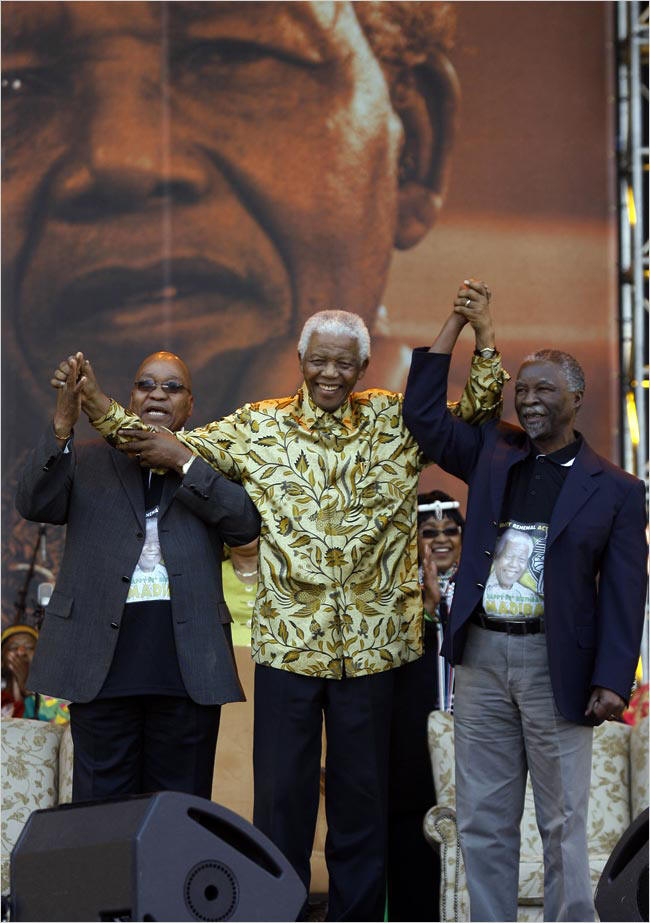

| JEROME DELAY/ASSOCIATED PRESS | |

| APPEARANCES ARE DECEIVING Jacob Zuma, left, and Thabo Mbeki, right, celebrate the birthday of Nelson Mandela shortly before Mr. Zuma's supporters forced out Mr. Mbeki as South Africa's president. |

| By DONALD G. McNEIL Jr. |

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |