| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

More Special Reports |

| Posted June 12, 2006 |

|

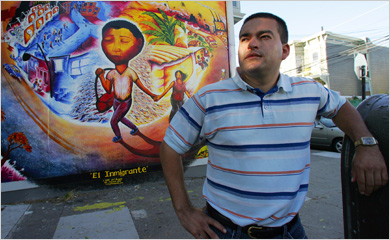

Jim Wilson/The New York Times |

| Celso Lima Mejia says he lost $6,600 to an immigration lawyer, who was latter disbarred. Mr. Mejia stood near a mural by the artist Joel Bergner. |

| Dollars and Dreams: Immigrants, as Prey |

| ________________________ |

By GARY RIVLIN |

| ________________________ |

I T was when his immigration attorney asked him for $3,000 several years ago that Celso Lima Mejia started to wonder whether his lawyer was taking him for a very costly ride. Mr. Mejia, a Guatemalan immigrant who was residing illegally in the United States, said he had already paid Miguel Gadda $3,600 to help him apply for asylum. Mr. Mejia recalled in a recent interview that Mr. Gadda promised him that the legal fees — a large chunk of his annual pay of about $20,000 as a handyman — would land him a coveted prize: a green card allowing him to come out from the shadows and live in the United States as a permanent resident.

But immigration authorities rejected the application, and Mr. Mejia said Mr. Gadda pressed him for the extra $3,000 to appeal the decision. Until that point, Mr. Mejia said, Mr. Gadda had done virtually no work on the case — "He hadn't even done any prep work with me before my hearing" — but his asylum application had revealed him to immigration authorities. Mr. Mejia, who is now 29, felt that he had to keep fighting, so he scrounged up the money. And that was the last time he saw Mr. Gadda.

When Mr. Mejia found a deportation order in his mail in 2001, he rushed in panic to his lawyer's office. "But the office wasn't there anymore, and there was nowhere to find him," said Mr. Mejia, who gained permanent resident status — his green card — after turning to a second lawyer he described as "my angel."

Mr. Mejia wasn't Mr. Gadda's only victim. When the State Bar of California disbarred Mr. Gadda in 2002, it cited him for professional misconduct and legal incompetence involving eight illegal immigrants he had advised. (Mr. Mejia's case was not among them.)

Mr. Gadda is hardly alone. As the number of illegal immigrants in the country has swollen to what the Department of Homeland Security conservatively estimates at nine million, so have the ranks of those who inhabit the immigration business's underbelly, posing as well-meaning advisers to those in search of a new job, a new home and a green card if not full citizenship. Immigrants, strangers in a foreign land for whom a green card means a ticket to a fuller life, are ideal prey for con artists and would-be consultants out for a quick buck.

ANALYSTS, lawyers and immigration specialists say that the current debate over immigration reform is also providing a perfect business environment for those who prey on the undocumented in the Chinatowns, barrios and other immigrant enclaves around the country.

|

|

Jamie Rector/The New York Times |

|

| Vivtor Nieblas, an immigration lawyer in Los Angeles, says talk of a new law on amnesty has helped prompt dishonest people to step forward to pray on the fears of people who are living in the United States illegally. | |

|

|

Peter DaSilva/The New York Times |

|

| Neilly Reyes, an immigration consultant in San Francisco, says that in the current climate, "People are saying, "Whatever it takes, whatever I must pay to become legal.' It's that attitude that people can take advantage of." | |

|

|

Jim Wilson/The New York Times |

|

| Nora Privitera, a lawyer in San Francisco, points out that many victims of shady immigration schemes are deported, making it less likely that the person or people who collected their money will be caught. | |

"Every time there's talk of a new law passing, these scammers basically pop up" and aim at immigrants, said Victor D. Nieblas, an immigration lawyer based in Los Angeles who teaches at Loyola Law School there. "It's big business."

The worst offenders, Mr. Nieblas and others said, tend to be immigration consultants, or "notarios" — nonlawyers who, whether or not they are qualified to do so, are in the business of helping aliens negotiate the immigration system. Even the name "notarios" rankles immigrant advocates: in many Latin American countries, a "notario público" is a professional licensed to represent people in legal matters.

"For unscrupulous attorneys and other practitioners, a change in the law represents a kind of open season on aliens," said Jennifer J. Barnes, the general counsel for the Executive Office for Immigration Review, a unit of the Justice Department. "That's what's happened in the past when we've enacted changes in immigration law, and I'm sure if a new law passes this time, we'll see people out there trying to take advantage of the situation."

Yet that seems to be happening already. People who closely monitor the national immigration debate may know that the House of Representatives and the Senate are so far apart on their immigration bills that no new amnesty laws may be enacted — but that information reaches illegal immigrants only in fractured pieces. Even then, immigrant advocates say, some notarios and others milking the process for financial gain warp and bend the true parameters of asylum opportunities to take advantage of legions of hopefuls.

Mr. Nieblas, who is a host of a weekly immigration advice program on a Spanish-language radio station in Southern California, said he was already hearing from callers who contended that local notarios were "asking them for money so they can start processing people under the new law, though there is no new law."

Lori A. Nessel, an associate professor at the Seton Hall University School of Law who runs its Immigration and Human Rights Clinic, has picked up on the same chatter on the East Coast.

"The concern is that you have these notarios out there saying, 'Pay now and get your applications in now for the amnesty,' when there's no reason to be taking people's money until there's a law," Professor Nessel said.

Nelly Reyes is a well-regarded immigration consultant in San Francisco who has spent the last 15 years helping her Spanish-speaking clients fill out forms, translate documents and navigate the federal bureaucracy. She earns roughly $60,000 a year, and says that she could make several times that amount if she emulated the practices of some of her more nefarious competitors. "I've gotten two or three calls over the last month from people saying, 'Let's go into business together, this is the time to start making a lot of money,' " Ms. Reyes said.

By her estimation, more than half her counterparts should be put out of business, because they are either scam artists or incompetents selling skills they do not possess.

"What's scary right now," Ms. Reyes said, "is that people are saying, 'Whatever it takes, whatever I must pay to become legal.' "

"It's that attitude that people can take advantage of," she added.

Over the past three years, Greg Abbott, the Texas attorney general, has secured judicial orders to shut down a dozen notarios around the state. That includes the Aplicación de Oro, a large immigration consulting firm in West Texas that a judge ordered closed in January after Mr. Abbott said that its two owners had "scammed" hundreds of immigrants out of thousands of dollars each, according to a press release. In California, the state attorney general, Bill Lockyer, has obtained civil judgments against roughly two dozen immigration consultants since 2000, a department spokesman said.

But advocates for immigrants say that California and Texas are the exception to the rule, and that most local district attorneys, who are also charged with monitoring consumer fraud, contend that their resources are too thinly stretched to devote much — if any — time to investigating immigration consultants. Moreover, advocates say, the problem is so widespread in California, Texas, New York and other states where illegal immigrants tend to live that even the most well-meaning efforts seem futile.

__________ |

|

| 'My mother basically spent her entire life's savings,' a daughter says. | |

__________ |

|

"The authorities will close down one of these shops, and a couple of weeks later they'll open up someplace else," said Mr. Nieblas, who is also an officer in the American Immigration Lawyers Association. "There are literally hundreds of these businesses in the Los Angeles area alone that are targeting the community."

At the moment, the most common fraud perpetuated on illegal immigrants — and certainly the most lucrative — is the kind that Mr. Mejia and his new lawyer believe almost had him sent back to Guatemala. "There are any number of immigration scams, but the asylum scam is by far and away the most popular right now," said Nora Privitera, a lawyer for the Immigrant Legal Resource Center in San Francisco. The brilliance of asylum fraud, at least from the perspective of the perpetrator, is that the federal government ends up sending most of the casualties back to their lands of origin.

"Their victims are typically deported and can't rat on them," Ms. Privitera said.

There are two general versions of the asylum scheme. The more simple of the two has a lawyer or notario convincing an illegal immigrant to pay the going rate of about $5,000 — more if a client is willing to pay for appeals — to apply for asylum. The payment changes hands, even though the illegal immigrant is unlikely to secure asylum status, which is meant for those who would face persecution back in their home country if they were deported.

That is among the accusations that the State Bar of California was leveling at Walter Pineda, an immigration lawyer, in a San Francisco hearing room last week. According to immigration experts, people typically emigrate from Mexico to search for better economic opportunities, not because they fear for their safety. Even so, Mr. Pineda routinely encouraged his Mexican clients to file "meritless" asylum applications, according to the state bar, which has accused him of more than two dozen counts of incompetence and five counts of moral turpitude for what it called "repeatedly and knowingly" lying to his clients.

The bar association contends that Mr. Pineda would routinely "take client money to file frivolous applications, spend no time actually trying to develop a viable position for the clients to stay legally in the United States, lose the applications for asylum and take more money to file frivolous appeals."

Doron Weinberg, Mr. Pineda's lawyer, said, "We admit to the general facts, but as you can imagine, we deny every judgment that has my client doing something reprehensible."

An immigration lawyer typically works hard for a $5,000 fee — assembling evidence, prepping witnesses, drawing up arguments to convince a skeptical immigration hearing officer that a client deserves asylum. Then there are cases like those of Mr. Mejia, the Guatemalan handyman who lost $6,600 pursuing his asylum case.

Guatemalan rebels kidnapped Mr. Mejia, the son of a government employee, when he was 7 years old and the country was in the midst of a prolonged civil war; two years after securing his release, his family fled Guatemala for the United States. Like so many illegal immigrants, Mr. Mejia and his parents did their best to live their lives out of the view of the authorities — until a family friend referred Mr. Gadda to them a half-dozen years ago.

Another lawyer might have been able to make a credible case that Mr. Mejia deserved asylum. But Mr. Gadda apparently was unwilling or unable to do so. Mr. Mejia says he believes his own experience reflects the accusations that the California bar made against Mr. Gadda: that he proved willing to collect fees but not to do the work for which he was paid.

"This was a lawyer who took money from his clients and repeatedly failed to perform legal services," said Sherrie B. McLetchie, the lead lawyer for the California bar in the disbarment proceedings against Mr. Gadda. And the undocumented "are among the most vulnerable clients any lawyer can represent," she said.

Despite his travails, Mr. Mejia stayed the course. It would eventually cost him over $10,000 more in legal fees beyond what he paid Mr. Gadda, but Ilyce Shugall, a local immigration lawyer, was able to secure him a green card in April. "I worked after work, and I worked on weekends," to pay the added fees, Mr. Mejia said.

Ms. Shugall said that Mr. Gadda "had made such a mess out of the asylum claim that we decided to drop it." Instead, Ms. Shugall, who works for the law firm of Van Der Hout, Brigagliano & Nightingale in San Francisco, pursued an alternative claim known as a "cancellation-of-removal" order. Such orders grant green cards to anyone who has lived in the United States for at least 10 years and can demonstrate that a parent or a child in the country legally would suffer "exceptional and unusual hardship" if the applicant was deported. Mr. Mejia, who arrived here in the late 1980's and later became the primary care provider for his ailing parents, met that criteria and won his green card.

MR. MEJIA was fortunate to have an advocate like Ms. Shugall, because cancellation-of-removal orders are often central to the other type of fraud involving an asylum claim. In it, a deceitful notario or lawyer tells potential clients that they qualify for a cancellation order, but does not disclose a crucial prerequisite: that even if they are care providers for a legal but ailing resident who is a parent or child, they must still prove that a loved one would suffer extreme hardship if the authorities deported the caregiver.

"That's a very difficult standard to meet, but people are not told that part of it," said Ms. Privitera of the Immigrant Legal Resource Center. The most insidious aspect of this unfortunate legal strategy, Ms. Privitera said, is that first the lawyer or immigration consultant must get someone into the system, because only if there is a removal order in place can someone petition to have the order rescinded, which would lead to a green card. The simplest way to do this is to request asylum, so the client will typically pay thousands of dollars for a futile asylum claim and, after the loss, will spend thousands of dollars more to pursue a legalization strategy that is far more likely to snare a deportation order than a green card.

"Once you're in immigration court, there's only two ways out," Ms. Privitera said. "You get granted something, or you get told to leave. There's no prosecutorial discretion for people who come into court because they've been defrauded."

Illegal immigrants who escape this trap are those who find a capable lawyer willing to take on their botched cases before they are deported — immigrants like Silvia Castillo of San Jose, Calif. Ms. Castillo, along with four other plaintiffs, has filed a suit accusing Rose Ann Martinez, an immigration consultant, and several San Francisco Bay Area lawyers of conspiring "on a fraudulent immigration scheme." Ms. Castillo, a housekeeper and single mother of two, said the process cost her about $10,000.

"My mother basically spent her entire life's savings," said Glancy Robles, her 16-year-old daughter.

According to the complaint, filed earlier this year in California, Ms. Martinez persuaded Ms. Castillo and her fellow plaintiffs, all of them illegal immigrants from Mexico, to pursue the cancellation-of-removal strategy. But, court papers say, Ms. Martinez never informed her clients that they also had to file an asylum application, which would put them in peril of deportation. The victims also contend that Ms. Martinez failed to tell them that a cancellation-of-removal order was rare and that they would be successful only if they also proved that their deportation would cause extreme hardship for a parent or child. Ms. Martinez declined to comment.

Because both of Ms. Castillo's children were born in the United States, they are citizens. But both are healthy. Ms. Castillo lost her case — and her family would have been forced to move back to Mexico if not for the intervention of Vaughan de Kirby, a San Francisco lawyer.

Mr. de Kirby was able to convince a judge that sending Ms. Castillo back to Mexico also meant deporting her two children, both of whom were in school at the time. He also was able to prove that her two daughters would experience extreme hardship if they were forced to leave the country, thereby clearing up the mess that he said Ms. Martinez — and the outside law firm she commissioned — had made of Ms. Castillo's case.

"Immigration consultants serve a valuable function, because they can operate at a cost factor for people who can't afford an attorney," Mr. de Kirby said. "But unfortunately they're not well regulated, and there are abuses."

Mr. Nieblas, the Los Angeles immigration lawyer, is not nearly so generous in his comments about notarios. He estimates that he meets with as many as 20 people a month who have shown up in his office after an immigration consultant has botched a case through incompetence or malfeasance. If it were up to him, he said, he would outlaw immigration consultants altogether. Another Los Angeles immigration lawyer, Alan R. Diamante, says that "70 to 80 percent of my clients have either been victims of a notario, or a lawyer working together with a notario." He, too, says he does not believe that notarios play a legitimate role in handling the legal mechanics of immigration.

LIKE other lawyers interviewed for this article, both Mr. Nieblas and Mr. Diamante said that they would never advise clients to reveal their residency status to authorities on the chance that they might secure a cancellation-of-removal order. He said that the stakes were very high, and the chances of winning low.

"I've had clients come to me and say, 'I've got a son who is suffering from this disease or that disease, let me turn myself in,' " Mr. Nieblas said. "I always tell them no. But some then just find someone else to handle the case. They've heard from people on the streets that this is the perfect opportunity to get a green card, and they don't want to believe me — and they can always find a notario who'll take their case."

The undocumented are not always on the losing end of immigration schemes. In Chinatown in San Francisco, for instance, an immigrant can spend $20,000 to $40,000 over six to seven years fighting to secure a green card, said Steve W. Baughman, a local immigration lawyer. Alternatively, he said, the same person can find an unscrupulous consultant who, for roughly $5,000, "will teach you how to lie and cheat your way into a bogus asylum claim."

For example, the granting of asylum is nearly automatic for a Chinese expatriate who claims religious and political persecution because he or she is a member of the Falun Gong spiritual sect. So some immigration consultants, Mr. Baughman said, maintain libraries of materials and videos about the group so that illegal immigrants can fake membership in Falun Gong when an asylum officer quizzes them.

"I can hardly blame people for doing it," he said. "It's the supply side that needs to be dealt with."

The federal government's Bureau of Immigration and Customs Enforcement, said Chris Bentley, a spokesman, does what it can to spread the word that illegal immigrants must be careful about whom they turn to when seeking legal assistance. "If people snuck in the country illegally, we still don't want them to be taken by someone hanging out a shingle on a street corner, claiming they're an immigration expert when they're not," Mr. Bentley said.

Yet the abuses of immigration consultants are hardly a top priority, Mr. Bentley acknowledged, for an agency now tucked inside the Department of Homeland Security.

The San Francisco district attorney's office will "vigorously prosecute any complaints we receive" about immigration consultants, said an assistant district attorney, June Cravett. Her office, she said, is trying to spread the word that it offers a haven for illegal immigrants who feel that they have been fleeced by a scam artist.

BUT limited resources mean that her office does not set up sting operations or the like, Ms. Cravett said. "Unfortunately, we haven't received that many complaints," she said.

The local authorities in Los Angeles have adopted a similar approach, said Mr. Diamante, a former president of the local Mexican American Bar Association. "They do one major token case every five years, it gets a lot of attention, and then that's it," he said.

Immigrant advocates and law enforcement officials in California point to the district attorney's office in Santa Clara County, in the heart of Silicon Valley, as a model enforcement program. But they say that while county officials have taken impressive steps to crack down on unscrupulous notarios, the office's experiences and limited resources still underscore how hard it is to rein in the problem.

"There are so many of them it's really hard to go after every single one," said Martha J. Donohoe, a deputy district attorney in the county who oversees her office's efforts to monitor immigration consultants. "Basically our focus has had to have been going after the really bad actors."

When she has a law clerk, Ms. Donohoe says, her office can monitor the immigration consultant industry more proactively. Otherwise, her office must wait until it receives complaints from local advocacy groups that represent illegal immigrants, she said.

"I hate to say it, but by the time we go after someone, they've typically hurt so many people," Ms. Donohoe said. "Typically it takes years to bring one of these cases, and the word has to really spread that someone is a bad, bad actor before we get people who are here illegally to bring a complaint."

Copyright 2006 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, SUNDAYBUSINESS, of June 11, 2006.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |