"In places like Miami and New York, chances are the person next to you in class is from somewhere else," said Danticat.

|

| Want to send this page or link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted October 3, 2002 |

| Diaries of Desperation |

| ____________ |

| By SUE CORBETT |

| Special to The Herald, |

| Fictional journals for young readers tell stories of fear and freedom |

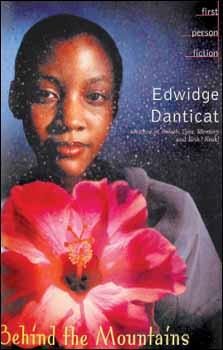

DIARY-STYLE BOOKS: Edwidge Danticat's 'Behind the Mountains' deals with a young Haitian.

Despots in Haiti and Nicaragua. Dictators in Panama and Cuba. Desaparecidos -- disappeared people -- in Argentina and Guatemala. Every political plague known to man has afflicted the countries of the Western Hemisphere -- and its children.

But where are those children's stories?

Mostly untold -- until now, when some long-overdue books have arrived.

Written by noted authors like the Haitian novelist Edwidge Danticat, Herald columnist Ana Veciana-Suarez and the Dominican novelist and poet Julia Alvarez, these poignant tales tell of childhoods trampled by political upheaval.

| "There are so many powerful books about the Holocaust,

beginning with Anne Frank's dairy, but when I searched for books about the things that

have happened in our hemisphere -- so many dictators, police states, genocide, the

disappeared people, the people forced into exile -- there was hardly anything,"

Alvarez said. "It is like there was an erasure ... almost nothing that explains to

American kids what it's like to have grown up under these conditions."

Alvarez's book, a dramatic

and heartbreaking novel titled Before We Were Free, is set in the Dominican Republic

before the fall of Gen. Rafael Trujillo. Veciana-Suarez's Flight to Freedom and Danticat's

book, Behind the Mountains, are part of a new series of dairy-style books about immigrants

called First Person Fiction -- meant not only for immigrant children, but for the

classmates they'll join when they arrive here. "In places like Miami and New York, chances are the person next to you in class is from somewhere else," said Danticat. |

|

`THE NEW GIRL'

Alvarez herself was once the new girl in class, fleeing the Dominican Republic in 1960 for New York. She sets Before We Were Free in her native land in that same year and tells the story through 12-year-old Anita de la Torre, whose cousins have left the country in a hurry. There are secret police parked in the driveway of her family's compound. A favorite uncle is in hiding. Trujillo is in power, but Anita overhears a conversation that leads her to believe her father may be part of a plot to overthrow him. (Trujillo was assassinated in 1961.)

The tension ratchets up, coming while Anita deals with the unsettling aspects of adolescence -- her first crush, her first period, conflict with her mother and sister.

Alvarez, who left the Dominican Republic when she was 10, is the author of the autobiographical novel How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents, about a Dominican family's adjustment to life in New York, and In the Time of Butterflies, a novel about the real-life sisters martyred during the Trujillo regime. She dedicates Before We Were Free ``to those who stayed.''

''It isn't my story, but it could have been,'' Alvarez said. ``All of us who are immigrants have this shadow story behind us.''

TWO WORLDS

Like Anita, 13-year-old Yara Garcia, the narrator of Flight to Freedom, is caught between two worlds and a little frightened of both. Veciana-Suarez, author of two books for adults, combined family lore with autobiography in telling Yara's tale -- a story that begins in rural Cuba with Yara forcibly enrolled in La Escuela de Campo, the backbreaking ''farm school'' where children worked in the fields from sunup to sundown.

''I personally have very little memory of Cuba, but I wanted to use the stories I had heard from my cousins and relatives,'' said Veciana-Suarez, who left Cuba at age 5. ``The things that happen in the book did happen to people I talked to. It's all based on fact.''

Once Yara arrives in Miami, the tension hardly eases.

''It is so awful to be a stranger, to not recognize any hallway or classroom or teacher. It is even worse not to understand what others are saying to you,'' Yara writes in her diary.

At home, Yara's older sister struggles with her parents' inconsistent embrace of American customs, a typical immigrant dilemma Yara sees this way: ``Just because my parents eat chocolate chip cookies doesn't mean they will allow Ileana to attend a party without a chaperon.''

FRETS ABOUT DAD

Like Anita, Yara is also forced to worry about her father, who she knows is involved in some sort of para-military training.

Veciana-Suarez's father, Antonio Veciana, was not only one of the original balseros, he was a founding member of Alpha 66, the militant anti-Castro group.

Yara's father refuses to make plans for holidays because he is sure the family will have returned to Cuba by then. When the talk turns to weddings one night, he tells Yara, ''I suppose you will want to get married in Los Pasionistas,'' a beautiful cathedral in Havana. Actually, Yara was thinking the church in her Miami neighborhood would be nice.

Both Veciana-Suarez and Danticat were approached by the editor of the First Person Fiction line, wondering if they'd be interested in writing something for young readers. Danticat said she was ''happy to sign on,'' particularly because the editor, Scholastic's Amy Griffin, had been involved with Scholastic's enormously popular ''Dear America'' books, historical fiction told in diary format.

HISTORY LESSONS

''I had given those books to the kids in my life,'' Danticat said. ``It's a great way of learning history in a fun way.''

Danticat grew up in Haiti, immigrating to Brooklyn when she was 12. Behind the Mountains chronicles a young girl's journey from violence in Port-au-Prince to a bittersweet reunion with her father in Brooklyn.

Growing up in Haiti, Danticat read the Madeline picture books and ''very serious French literature.'' Once she arrived in New York, she read Nancy Drew.

''But no matter what culture you're from, you're looking for some kind of connection,'' she said. ``You're looking for a mirror. I didn't see myself in any of the books I read at that age.''

In Behind the Mountains, 13-year-old Celiane Esperance is missing her father, who has left their home in the Haitian hills five years earlier to earn a living in New York. He sends money each month, but permission for the family to leave has not been granted.

BOMB INJURES MOM

When Celiane, her mother and brother travel in Haiti to visit an aunt, they are victims of election season violence -- a pipe bomb strikes their bus, seriously injuring Celiane's mother. Afterward, they feel increasing pressure to get to New York. Once they do arrive, Celiane experiences some of the same anguish Yara did in her story, set in Miami, 40 years earlier.

Authors often refuse to have expectations about what readers will take from their books, but Danticat doesn't hesitate when it comes to Behind the Mountains.

''I hope they get a glimpse of what it's like for a young person to come here and start over,'' she said, ``and an idea of what things were like where they came from.''

LOOKING BACK

Veciana-Suarez says writing the book was a learning experience for her -- having to think more about her own heritage and get specifics about a past she doesn't fully remember.

'When I was writing, I asked my mom, `What restaurants would we have gone to in the mid-60s?' '' Veciana-Suarez recalled. 'She said, `We didn't go to restaurants. We didn't have any money.' I was too young to realize how tough it was for them.''

These diaries appeared in The Miami Herald of October 3, 2002.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |