| Dependent on Jail, City of Immigrants

Fills Cells With Its Own - December 27, 2008 |

|

|

|

|

| A woman and her son prepare to visit her husband, an

immigration detainee at the Donald W. Wyatt Detention Facility in Central

Falls, R.I. It opened in 1993 to hold people charged with federal crimes

like drug dealing, but last year, after doubling in size, it began locking

up thousands of immigrants that the government wants to deport. Photo:

Suzanne DeChillo/The New York Times |

|

|

|

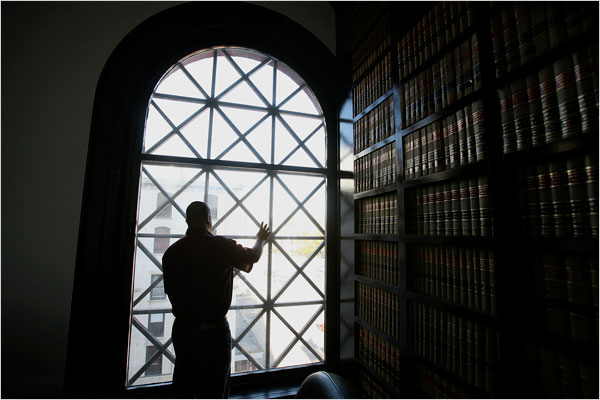

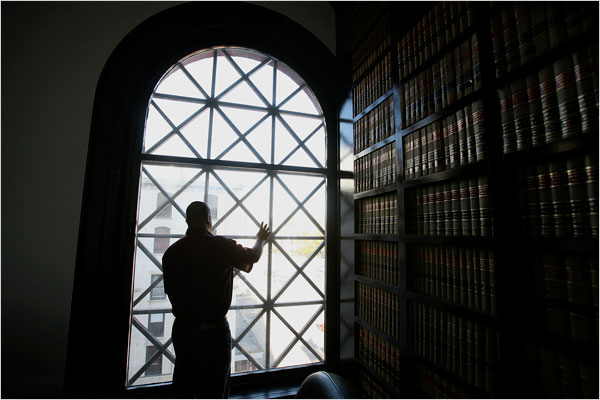

| Maynor Canté, a longtime Central Falls resident, at his

lawyer's office in Providence. One day last year immigration agents picked

him up outside his front door and delivered him to Wyatt in chains. Photo:

Suzanne DeChillo/The New York Times |

|

|

|

| Mr. Canté leads a prayer group for fellow Guatemalans at

St. Matthew's Roman Catholic Church in Central Falls. For three days after

his arrest by immigration agents, his family didn't know where he was. After

calls to many jails, a friend learned that he was at Wyatt, only blocks from

home, but in a separate world. Photo: Suzanne DeChillo/The New York Times |

|

|

|

| Inside a control room in the 722-bed Wyatt jail, where the

federal government pays $101.76 a day for each detainee. "We do what we get

paid to do," said Anthony Ventetuolo, the jail's chief executive, left. "I'm

not interested in getting involved in the politics of immigration." Photo:

Richard Perry/The New York Times

|

|

| Mr. Canté's sisters borrowed money to hire a lawyer, Lidia

Sanchez, left. Though she reopened his case for a hearing in Boston, he

ended up as one of 2,000 detainees in a privately run tent city in Texas.

"You almost have to wonder whether there's some kind of policy to track down

these undocumented persons just to fill up these detention centers," she

said. Photo: Suzanne DeChillo/The New York Times |

|

|

|

|

| Mr. Canté's priest, the Rev. Otoniel Gomez, prepares to

celebrate Mass in Spanish at St. Matthew's, built in the 1920s by French

Canadian immigrants. These days, their descendants are sometimes openly

hostile to Latino immigrants, he said: "They might think they're not dealing

with human beings. Now with the economy, they're blaming the immigrants, and

that's injustice." Photo: Suzanne DeChillo/The New York Times |

|

|

|

| Central Falls is set in the river valley where America's

industrial revolution was born. In 1895, local farmers saw their political

power threatened by foreign-born mill workers -- French Canadians, Irish and

Poles -- and voted to make the tenement section of their community a

separate city: Central Falls. The most prosperous, tax-paying industries

remained in nearby Lincoln, R.I. Photo: Suzanne DeChillo/The New York Times |

|

|

|

| Cesar Quiroa, 10, the son of Guatemalan immigrants, plays

on the Little League team sponsored by the jail. Named for the United States

marshal who championed it, Wyatt was pitched as an economic engine that

would bring money and jobs to the depressed community, now mostly Latino.

Photo: Richard Perry/The New York Times |

|

|

|

| The Central Falls Panthers practice in the shadow of Wyatt. The

mother of one player said she worried that her sister's teenagers

would end up inside because they had no path to legal status. In

December, immigration authorities transferred all immigration

detainees to other jails while they investigated a death in custody.

Wyatt is now scrambling to fill its beds with inmates from other

states -- many of them murderers and rapists -- and to win back a

share of the growing market in immigration detainees. Photo: Suzanne

DeChillo/The New York Times |

|

|

|

| Recruits training to be correction officers march into Wyatt.

Central Falls residents were promised preference in hiring, but only

10 of about 200 employees live in the city. Photo: Suzanne DeChillo/The

New York Times |

|

|

|

| Olga Vasquez, 29, holds a picture of her son Gerson, 9, back in

rural Guatemala. She was one of 31 courthouse cleaners arrested in

an immigration sweep in July. After 10 days in Wyatt, she was

released with an electronic ankle bracelet, and she was later

charged with using a false document to get the cleaning job, which

paid $7.40 an hour. Inmates on the Wyatt cleaning crew are paid 40

cents a day. Photo: Suzanne DeChillo/The New York Times |

|

|

|

| More than 800 people attended a Spanish-language Mass at St.

Matthew's in November. "People know they cannot be caught in

church," Father Gomez said. "I tell them, you are secure here." He

added: "They live in fear. I tell them, 'If we live in fear, we are

already dead.'" Photo: Suzanne DeChillo/The New York Times |

|

|

|

| Charles D. Moreau, left, the mayor of Central Falls, at a car

show on Dexter Street in October. Mayor Moreau backed the expansion

of the Wyatt jail, but criticized the immigration crackdown that

brought it detainees. "One has nothing to do with the other," he

said. Photo: Suzanne DeChillo/The New York Times |

|

|

|

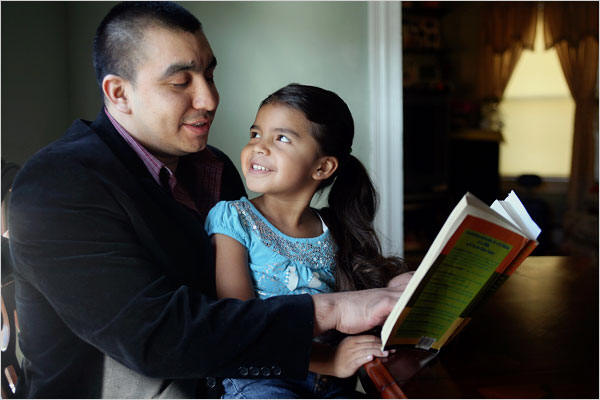

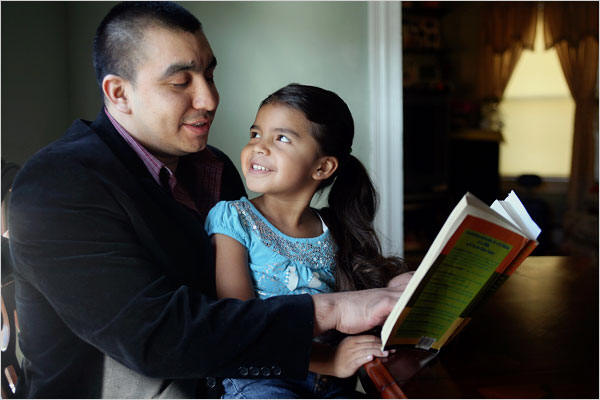

| Maynor Canté and his niece Daisy, 5, a United States citizen,

are together again after his three-month detention odyssey. At the

last minute, his lawyer persuaded the government to fly him back

from Texas. He was granted authorization to work pending an

immigration hearing in December 2009. "In all these years I've been

here illegally, everywhere I went, everything I used to do, I used

to feel like a reject," said Mr. Canté, 27, whose siblings are all

legal residents. "Now I feel like I've been accepted for the

community. I don't feel afraid anymore. I feel, like, free." Photo:

Suzanne DeChillo/The New York Times |

|