| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted May 1, 2004 |

Demonizing Fat in the War on Weight |

|

Corbis |

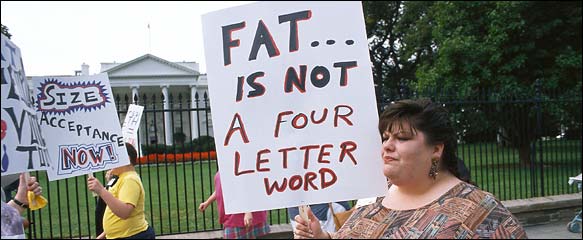

| Overweight people marched at the White House in 1994, above, to protest negative attitudes toward fat. Social historians say stigmatizing size is a relatively recent phenomenon, dating only from the 19th century. |

| _______________ |

By Dinitia Smith |

| _______________ |

Almost every day, it seems, there is another alarming study about the dangers of being fat or a new theory about its causes and cures. Just this week, VH1 announced a new reality show called "Flab to Fab," in which overweight women get a personal staff to whip them into shape.

But a growing group of historians and cultural critics who study fat say this obsession is based less on science than on morality. Insidious attitudes about politics, sex, race or class are at the heart of the frenzy over obesity, these scholars say, a frenzy they see as comparable to the Salem witch trials, McCarthyism and even the eugenics movement.

"We are in a moral panic about obesity," said Sander L. Gilman, distinguished professor of liberal arts, sciences and medicine at the University of Illinois in Chicago and the author of "Fat Boys: A Slim Book," published last month by the University of Nebraska Press. "People are saying, `Fat is the doom of Western civilization.' "

Now, says Peter Stearns, a leading historian in the field, the rising concern with obesity "is triggering a new burst of scholarship." These researchers don't condone morbid obesity, but they do focus on the ways the definition of obesity and its meaning have shifted, often arbitrarily, throughout history.

Mr. Stearns, provost and professor of history at George Mason University, has written that plumpness was once associated with "good health in a time when many of the most troubling diseases were wasting diseases like tuberculosis." He traces the equation of obesity and moral deficiency to the late-19th and early-20th centuries. In 1914, an article in the magazine Living Age, for example, stated, "Fat is now regarded as an indiscretion and almost a crime." Mr. Stearns cites it in an essay he wrote for the aptly named "Cultures of the Abdomen," a collection to be published by Palgrave Macmillan next November, edited by Christopher E. Forth, a senior lecturer at Australian National University, and Ana Carden-Coyne, a lecturer at the University of Manchester, in England. During World War I, Mr. Stearns writes, some popular magazines actually said that eating too much and gaining weight were unpatriotic, presumably because of concerns about food shortages.

In "Fat Boys," Mr. Gilman describes how plumpness used to be associated with affluence and the aristocracy, while today it is associated with the poor and their supposedly bad eating habits. Louis XIV padded his body to look more imposing. During the French Revolution, obesity inspired a rallying cry, "The People Against the Fat," he says. And whereas once the fat man was generally seen as hypersexual, like Falstaff, now he is seen as asexual, like Santa Claus.

| A countercrusade to untangle health and obesity from morality. |

The first popular modern diet book, "Letter on Corpulence Addressed to the Public," written by William Banting, an undertaker, appeared in 1863. Banting wrote that when he was fat he was regarded as a useless parasite. He went on a diet and lost 35 pounds. "I can honestly assert that I feel restored in health, `bodily and mentally,' " he wrote. Before long, Mr. Gilman points out, the word "banting" became a synonym for dieting.

In Mr. Stearns's view, 19th-century changes in attitudes toward obesity were a guilty reaction to the new abundance of food, the rise of the consumer culture and the growth of sedentary work habits. "I don't think we were comfortable with it because of religious legacies and hesitations," he said in an interview. "Having a target for self-control, like dieting, helped express but also reconcile moral concerns about consumer affluence," Mr. Stearns writes; the dieting fad become a new kind of Puritanism.

Other contemporary scholars see a more dangerous underside to the current campaign against fat. Paul Campos, a professor of law at the University of Colorado, argues that obesity is used as a tool of discrimination, citing disturbing similarities to the eugenics movement, with its emphasis on "improving" the species. Obesity in America is "primarily a cultural and political issue," Mr. Campos writes in his new book, "The Obesity Myth" (Gotham), due out this month. "The war on fat," he argues, "is unique in American history in that it represents the first concerted attempt to transform the vast majority of the nation's citizens into social pariahs, to be pitied and scorned."

In what may turn out to be his most controversial claim, Mr. Campos writes: "Contrary to almost everything you have heard, weight is not a good predictor of health. In fact a moderately active larger person is likely to be far healthier than someone who is svelte but sedentary." To bolster his argument, he cites several studies, including one published by the Cooper Institute, a private research institution in Dallas.

Most medical experts warn of the dangers of fat, but Mr. Campos disagrees. "There is no good evidence," he writes, "that significant long-term weight loss is beneficial to health, and a great deal of evidence that short-term weight loss followed by weight regain (the pattern followed by almost all dieters) is medically harmful."

He said in a recent interview: "The current hysteria about body mass and supposedly devastating health effects is creating a stratification in the society of power and privilege based on a scientifically fallacious concept of health. What we are seeing with this moral panic over fat in many ways is comparable to what we saw with the eugenics movement in the 20's."

Kathleen LeBesco, associate professor of communication arts at Marymount Manhattan College, also asserts that at the root of the current slimness craze is an effort to stigmatize certain groups.

In a new book, "Revolting Bodies" (University of Massachusetts Press), Ms. LeBesco writes that African-American and Mexican-American women are particularly targeted as obese in contemporary culture. "All of the discourse about fatness is about pathologizing the individual," she said in an interview, also likening it to the eugenics movement.

She refers to a study by the Centers for Disease Control in which the highest proportions of overweight people are said to be African-American women and Mexican-American women. "Is it coincidence that representatives of these two stigmatized racial and ethnic groups, as well as women, are most likely to be obese?" Ms. LeBesco writes.

She also says that the diet industry is increasingly trying to concentrate on minorities. She disapprovingly cites a National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute study that concludes that full-figured African-American women have positive attitudes toward their bodies. Those self-confident feelings, the study said, "may be a barrier in attempting to work with overweight African-American women who — although they may want to weigh less and be healthier — do not necessarily consider themselves unattractive or overweight, and may value cosmetic aspects of body weight less."

Mr. Stearns has charted the way women in general gradually became the targets of obesity campaigns. The 19th-century feminist Elizabeth Cady Stanton was praised for her "mature figure," he says. "Feminist leaders who were more slender were reproved," Mr. Stearns writes, perhaps because of "the traditional linkage between thinness and discontent."

Then, around the 1890's, suddenly, women were being urged to diet. "Fat began to be obsessively discussed," Mr. Stearns writes. The Gibson girl was rendered as slender, and the weight of Miss America in relation to her height decreased from the 1920's on.

The emphasis on slenderness in women was no accident, Mr. Stearns says. At the same time women were being urged to lose weight, the ideal of motherhood was declining and women were able for the first time to express an appetite for sex. "Dieting was a way, again, to express virtue and self-control even in a changing sexual climate," he writes.

And while there are many causes for obesity — cheaper food, more aggressive marketing, bigger portions in restaurants and, of course, increasingly sedentary habits — Mr. Stearns says that gaining weight is still seen as a moral issue, "a sign you were lazy, lacked self-control."

He notes that the French have been more successful at weight loss than Americans, partly, he says, because weight loss in France is based on aesthetics, not morality.

Mr. Stearns insists he is not promoting obesity but rather arguing that making people feel guilty for being fat is a useless form of weight control. In describing the contemporary ethos, he said: "If you fail to lose weight you are demonstrating you're a bad person. It's a big burden. Faced with this additional pressure you are even more likely to end up by saying: `The hell with it! I'm going to get ice cream. I am such a bad person I need to solace myself.' "

Copyright 2004 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Arts & Ideas, of Saturday, May 1, 2004.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |