| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted July 5, 2003 |

| Criticism of a Hero Devides Blacks |

|

Agence France-Presse |

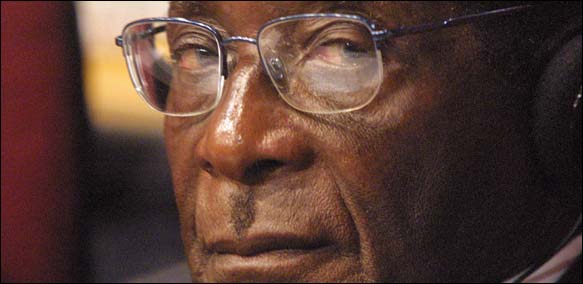

Liberator or despot? Above President Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe. |

By RACHEL L. SWARNS |

WASHINGTON, July 4 — When the TransAfrica Forum decided to speak out last month against Zimbabwe's president, Robert Mugabe, for condoning the jailing, beating and killing of black opposition party supporters, it shouldn't have been all that surprising.

After all, for decades, TransAfrica, a research and lobbying group based here, has been speaking out on the struggles of Africans on the continent and elsewhere. In the 1980's, for instance, it led the anti-apartheid marches that helped press the American government to change its policy of "constructive engagement" with the white government of South Africa.

In the 90's the group protested against the repressive black regimes in Haiti and Nigeria.

In this latest action TransAfrica's president and other prominent black Americans from Africa Action, an advocacy group here; Howard University; and church and labor unions wrote a public letter to Mr. Mugabe, assailing what they described as the "increasing intolerant, repressive and violent policies of your government."

| ______________________________________ |

| Deciding how to respond to African authoritarians. |

| ______________________________________ |

But the decision to condemn Mr. Mugabe publicly — which was hailed as long overdue in some quarters — has also touched off an outcry among some black intellectuals, activists and Africa watchers. Mr. Mugabe, who has led Zimbabwe since white rule ended in 1980, is still considered a hero by some African-Americans. And in some e-mail messages and on radio talk shows, the signers of the letter have been described as politically na´ve, sellouts and misguided betrayers of Africa's liberation struggle.

Angry critics have sent e-mail messages to those who signed the letter, saying in one instance that they "do not represent African-Americans." On a left-leaning radio station in New York City, WBAI-FM, several people have called to complain. "Whatever black Africans in Zimbabwe decide to do," said a caller who identified herself as Missy from Queens, "I think black Africans here, we should join them."

The furor has highlighted a long-simmering debate about how to respond to authoritarian leaders in Africa when those leaders happen to be black.

Bill Fletcher Jr., the president of TransAfrica, says black Americans cannot afford to romanticize African leaders if they hope to remain relevant to the struggles on the continent. They must be willing to condemn wrongdoing, he said, even if that means criticizing some revered leaders.

"When the enemy was evil white people in South Africa, that was easy," Mr. Fletcher said in an interview at his office here. "But when the enemy becomes someone who looks like us, we're very skittish about taking that on."

"It's very difficult to accept that a ruling class has emerged in Zimbabwe that is oppressing its own people, but you've got to face the reality," he said. "I felt like we had to speak out."

Mr. Fletcher said African-Americans had often been on the right side of history, supporting African leaders who fought against white rule and then worked for their people, including Nelson Mandela of South Africa, Julius K. Nyerere of Tanzania; and Samora Machel of Mozambique, among others. Mr. Mugabe, who expanded access to education and health care, was also praised for more than a decade by Western governments as well as by blacks for building one of Africa's most prosperous nations.

But when white governments began to fall away, thorny questions began emerging. In the 70's some blacks quietly questioned whether they should continue supporting Uganda's violent despot, Idi Amin, but decided against criticizing him publicly. In the 80's some Africa watchers made a similar decision about Angola's government, which was dogged by complaints of corruption.

In 1996 Carol Moseley Braun, an Illinois Democrat who was a senator then, stirred a furor when she flew to Africa to visit Gen. Sani Abacha, Nigeria's corrupt dictator. By then TransAfrica and other prominent black individuals and organizations had already launched a public campaign to criticize and isolate Nigeria's government, which was detaining and killing its critics.

In the criticism of Zimbabwe, Mr. Fletcher was joined by Salih Booker, director of Africa Action; William Lucy, president of the Coalition of Black Trade Unionists; Horace G. Dawson Jr., director of the Ralph J. Bunche International Affairs Center at Howard University; the Rev. Justice Y. Reeves of the Progressive National Baptist Convention; the coordinating committee of the Black Radical Congress and others.

"We view the political repression under way in Zimbabwe as intolerable and in complete contradiction of the values and principles that were both the foundation of your liberation struggle and of our solidarity with that struggle," the group said in its letter to Mr. Mugabe.

| ______________________________________ |

| Is it na´ve to find fault with black governments' wrongdoing? |

| ______________________________________ |

Critics complain, however, that Mr. Fletcher and his colleagues are playing down the importance of the ongoing struggle for land in Zimbabwe. They say Mr. Mugabe has been demonized in the West because he decided to seize white-owned farms on land stolen from blacks during British colonial rule. Zimbabwe's tiny white minority — less than 1 percent of the population — owned more than half of the fertile land until the government began seizing most of it in 2000.

"I'm not on his side with respect to his repression of the opposition," Ronald Walters, a professor of government and politics at the University of Maryland, said of Mr. Mugabe. "But I am on the side of the people who claim there's a justice issue in terms of the land. You can't escape the racial dynamic, and you can't escape the political history."

Some critics say the violence in Zimbabwe has mostly occurred between supporters and opponents of land redistribution. They also fear that the Bush administration, which has already signaled that it might intervene in war-torn Liberia, might use the letter from TransAfrica and Africa Action to suggest that prominent black Americans favor an American intervention in Zimbabwe.

Mr. Fletcher and Mr. Booker say they would vigorously oppose an American-led military intervention in Zimbabwe. TransAfrica also opposes the idea of sending American troops to Liberia, saying an African peacekeeping force financed by the American government would be preferable.

"I'm sympathetic to it," Mr. Walters said of the stance taken by TransAfrica and Africa Action. "But this letter makes them sound like the guys who simply want to beat up on Mugabe just because he took land from some white people."

Mark Fancher, who heads the international affairs unit of the National Conference of Black Lawyers, raised similar concerns. He said Mr. Mugabe's critics neglect to note that he still has support among some Zimbabweans, even though he has been widely accused of rigging last year's presidential election.

"The one thing nobody disputes is that, whether he won or not, Mugabe got a lot of votes," Mr. Fancher said. "This is an African problem, a Zimbabwean problem. For people who are really disconnected from the day-to-day lives of people in Zimbabwe to reach these kinds of conclusions, we don't feel that's appropriate." But Mr. Fletcher and Mr. Booker of Africa Action say Mr. Mugabe's supporters are not paying attention to what is happening on the ground. Much of the seized farmland that was intended for the poor has actually ended up in the hands of Mr. Mugabe's friends and political allies.

Mr. Mugabe emphasizes the importance of redistributing land now, but during much of the 90's it was not a priority for his government, some of his supporters acknowledge. He focused on the issue, which resonates with many black voters only when it became clear that a powerful black opposition party was threatening his grip on power.

And despite rhetoric to the contrary, the majority of victims of political violence in Zimbabwe are not white farmers, the police and human rights groups say. They are mostly ordinary black people who dared to support or vote for the opposition.

Moses Mzila-Ndlovu, a senior member of Zimbabwe's opposition party, hailed the statement from TransAfrica and the others as an important step. But he wondered why it took so long for the groups to speak out.

Mr. Booker said he, Mr. Fletcher and others had first tried to work behind the scenes, meeting with Zimbabwean diplomats and urging them to respect human rights and to initiate formal talks with the opposition to improve the deteriorating political situation.

When that failed, he said, they wrote their letter.

"Mugabe was my hero," said Mr. Booker, who worked at TransAfrica in the 80's and helped arrange Mr. Mugabe's first visit to the White House. "He was a liberator, the defiant hero. Zimbabwe was a country where we had a lot invested emotionally and politically."

"But we had to ask ourselves: `Who are we in solidarity with in southern Africa? The aging heroes or the new African civil society?' he said. "It's not just about Zimbabwe. We have to be clear who our allies are. We should not be standing shoulder to shoulder with African governments who are abusing their own people. The time had arrived for us to take a public stance."

Copyright 2003 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Arts & Ideas, of July 5, 2003.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |