| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted May 31, 2003 |

|

Associated Press |

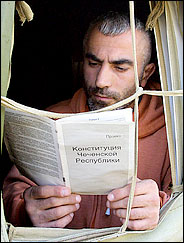

| People like this Chechen, who is reading a proposed constitution, must feel they are part of the drafting process, experts say. |

Constitutionally, |

A Risky Business |

By FELICIA R. LEE |

In the last 35 years, more than 100 countries have tried to accomplish what Iraq is trying to do: create a democratic constitution.

While some countries have succeeded, many others have been stymied by ethnic and religious hatreds, differences over power divisions and deeply rooted corruption or violence.

Drafting a constitution is often the first step in transforming a country to democracy, but the questions seem to be endless. Parliament or president? Centralized or decentralized authority? Ethnic and religious power-sharing or majority rule? Who can vote? What is the scope of judicial review? Is there a right to housing and jobs? And who should answer these questions?

This formidable task has produced a cottage industry of constitutional consultants. Experts in areas like conflict resolution, law, development and political science have taken on the tough nuts-and-bolts work of converting high-minded ideals and aspirations into workable laws, rules and institutions.

If there is one conclusion that can be drawn from these experiences, it is that there is no one right way to do the job.

"There is a fantasy that constitutional law is an appliance you plug in in New York and then plug in in Budapest or Baghdad," said Stephen Holmes, a professor of law at New York University Law School. Rather, he said, "provisions of a constitution interact with each other in unpredictable ways." he said.

Mr. Holmes directs that advice in particular to American scholars, who tend to dominate the constitution-advice business. Americans are often seduced by the mythology of their own constitution, the oldest written democratic constitution, as a document that can and should be reproduced around the world, he said.

Bereket Habte Selassie, a professor of law and African studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, agrees. "In the 1950's, Europeans summoned African leaders from 25 to 30 countries to capitals like London, Paris and Brussels and shoved constitutions down their throats," he said. "The leaders of those countries became autocrats," which he sees as evidence that imposing foreign models does not work.

That doesn't mean outside advice and other models are useless, said Mr. Selassie, who helped draft the constitution for his native Eritrea, which was ratified in 1997. He is chairman of a group on constitutions at the United States Institute of Peace, a government-sponsored research group in Washington.

The institute is examining about 140 cases of constitution writing and has begun to identify guidelines to reduce conflict and violence. They include having the incumbent head of state not succeed himself; waiting two or three years before a regular election; and creating a constitutional court to resolve differences of opinion about where authority lies, say in a tussle between a president and a prime minister.

Mr. Selassie said an overriding principle in the process "is the participation of the people." He said, "The thing is to make them feel they own the constitution." Even illiterate citizens can listen to radios or attend meetings, he said.

Many countries begin the process by identifying their biggest problems and then using the constitution to fix them. Cass R. Sunstein, a professor of political science and law at the University of Chicago, calls this approach countercultural.

"The Americans were very alert to this," said Mr. Sunstein, who worked on the creation of constitutions in Poland, South Africa, Ukraine, Russia and Lithuania. "The Bill of Rights is just partly a set of recollections of what went wrong under the British."

In South Africa one of the legacies of apartheid was mass poverty, so one of the important provisions of that constitution was the right to shelter. Many Eastern European countries, emerging from Communism, included language about freedom of contract and private property in their constitutions.

Just this week, Rwanda, which was torn apart by genocidal attacks, ratified a multiparty, democratic constitution that has clauses on limiting ethnic and regional divisions and forbidding discrimination on the basis of ethnicity. It also reserved one-third of the parliament seats for women.

While Mr. Sunstein contends that the best constitutions are countercultural, he adds that there has to be a balance between aspirations driven by recollections of oppression and things that can be enforced by law. Some drafters of the Ukraine constitution, for example, wanted a provision that would require the press to be objective, which Mr. Sunstein said would violate freedom of expression and be unenforceable.

In Brazil, which has a history of military dictatorship and whimsical institutional leadership, the constitution is full of provisions that are not easily enforced (like protecting the jobs of pregnant women).

But some scholars argue that is the price of creating constitutional legitimacy. Melanie Beth Oliviera, a social scientist, says of the constitution in Brazil, "Legal scholars will tell you that document is totally unwieldly, but people said, `I see my voice in this document.' "

An open process also confers legitimacy, said Timothy D. Sisk, a professor of international studies at the University of Denver, but can slow the creation of a workable constitution. Secrecy allows for trade-offs and deals that are not politically palatable, Mr. Sisk said. "In South Africa they had over one million submissions about the different clauses and aspects of the constitution, from employers' ability to lock out employees to the rights of women and children," Mr. Sisk said.

The South Africans also struggled to balance majority prerogatives and minority rights. One of the most ferocious debates was over the right to be educated in the language of one's choice in a country that has 11 official languages, he said. In the end, the South Africans decided to allow all languages in the schools.

"What do constitutions really do?" Mr. Sisk asked. "They set the rules for future interaction, so conflict can be negotiated and settled."

The issues and conflicts that have cropped up in constitutions worldwide are clearly visible in Iraq. Scholars are already weighing in on how laws and institutions can reflect the principles of federalism, democracy, nonviolence, respect for minorities and a role for women. These were among 12 principles that emerged from a gathering of Iraqis in Ur in late April.

This month the Public International Law and Policy Group and the Century Foundation, which provide policy analysis and legal services to countries in transition, prepared a 58-page report on establishing an Iraqi constitution. It included ideas about protecting minority and human rights, choosing a state structure and building an electoral system.

Even with all the expert advice, "It's not going to be a bunch of academics giving them a constitution," said Paul R. Williams, a professor of law and international relations at American University, who worked on the report. "It's going to be the end product of a lot of political bargaining, a fierce political bargaining process."

For all the difficulties, said Barnett R. Rubin, a political scientist who has been working on the Afghanistan Reconstruction Project, "Writing constitutions is easy compared to implementing them."

Copyright 2003 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Books & Arts, of May 31, 2003.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |