| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted March 20, 2007 |

| Communist Party USA Gives Its History to N.Y.U. |

|

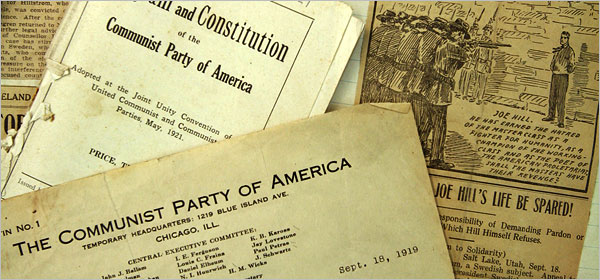

Michael Falco for The New York Times |

| The vast collection from The Communist Party USA includes personal letters, smuggled directives and photographs. |

____________ |

|

By PATRICIA COHEN |

THE songwriter, labor organizer and folk hero Joe Hill has been the subject of poems, songs, an opera, books and movies. His will, written in verse the night before a Utah firing squad executed him in 1915 and later put to music, became part of the labor movement’s soundtrack. Now the original copy of that penciled will is among the unexpected historical gems unearthed from a vast collection of papers and photographs never before seen publicly that the Communist Party USA has donated to New York University.

The cache contains decades of party history including founding documents, secret code words, stacks of personal letters, smuggled directives from Moscow, Lenin buttons, photographs and stern commands about how good party members should behave (no charity work, for instance, to distract them from their revolutionary duties). By offering such an inside view, the archives have the potential to revise assumptions on both the left and the right about one of the most contentious subjects in American history, in addition to filling out the story of progressive politics, the labor movement and the civil rights struggles.

“It is one of the most exciting collecting opportunities that has ever presented itself here,” said Michael Nash, the director of New York University’s Tamiment Library, which will announce the donation on Friday.

Liberal and conservative historians, told by The New York Times about the archives, were enthusiastic about the addition of so many original documents to the historical record. No one yet knows whether they can resolve the die-hard disputes about the extent of the links between American subversives and Moscow since, as Mr. Nash said, “it will take us years to catalog.” But what is most exciting, said Mr. Nash and other scholars, is the new areas it opens up for research beyond the homegrown threat to security during the cold war.

Hill’s last rhyme — which begins, “My Will is easy to decide/ For there is nothing to divide” — was discovered in one of the 12,000 cartons. (Hill was convicted, some thought wrongly, of murder.) In other boxes were drafts of the party’s programs with handwritten editing changes and a stapled copy of its first constitution. “The Communist Party is a fact,” C. E. Ruthenberg, the executive secretary wrote on Sept. 18, 1919, days after the founders met in Chicago. A 1920 document marks the merger of the Communist Party and the Workers Party. It lists “Dix” as the secret party name of Earl R. Browder, who would later become general secretary of the party, “L. C. Wheat” as Jay Lovestone, who later turned against communism and worked with the A.F.L.-C.I.O. and the C.I.A., and Alexander Trachtenberg as “one of the confidential agents of Lenin in America.”

From years of being folded, many of the pages are impressed with grooved lines like wrinkled faces; others are scarred by cigarette burns and thin as onion skin. Some folders, filled with crumbling artifacts, look as if they’ve been sprinkled with yellowed confetti.

Ruthenberg underscores the “secret manner in which the party is conducted.” The Los Angeles branch, known as “XO1XO5” uses the password “ ‘Kur-heiny,’ which means: ‘Are you advancing?,’ ” he writes. “The answer is: ‘Teip,’ meaning ‘yes.’ ”

He copies a letter signed by the Russians Nikolai Bukharin and Ian Berzin that he said was hidden in the coat lining of a Bolshevik about how the Americans should operate. The two order the party to urge soldiers and sailors to agitate “against officers” and to arm workers. They warn against allowing members to engage in philanthropic or educational activities, insisting that they form “FIGHTING ORGANIZATIONS FOR SEIZING CONTROL OF THE STATE, for the overthrow of government and the establishment of the workers’ dictatorship.”

Robert Minor, a cartoonist and radical who covered the Russian civil war, has a clear-eyed and lyrical account of an interview with Vladimir Lenin in Moscow, dated December 1918. Lenin was fascinated by America, calling it a “great country in some respects,” and shot question after question at Minor: “ ‘How soon will the revolution come in America?’ He did not ask me if it would come, but when it would come.” Minor, who had not yet joined the party, found Lenin a bewitching figure. “When he thunders his dogma, one sees the fighting Lenin. He is iron. He is political Calvin,” Minor says in his typewritten notes. “And yet, Calvin has his other side. During all the discussion he had been hitching his chair toward me,” he writes. “I felt myself queerly submerged by his personality. He filled the room.”

As he leaves the Kremlin, Minor notices two men drive up in limousines. “A few months ago they were ‘bloodthirsty minions of predatory capital,’ ” he writes, “But now they are ‘people’s commissaries’ and ride in the fine automobiles as before, live in the fine mansions.” They rule “under red silk flags to protect them from all disorders. They have learned the rose smells as sweetly under another name.”

That description is “very important,” said John P. Diggins, a historian at the Graduate Center at the City University of New York. He said he expected a lot of new dissertations and books to result from the new archives. Historians have spent too much time arguing about the party’s subservience to Moscow, he said, neglecting Communists’ work in organizing labor and fighting racism, and their philosophical take on Marxism.

Every box offers up a different morsel of history. One contains a 1940 newsletter from students at City College in New York criticizing Britain for betraying the Jews in Palestine; another has a 1964 flyer from the Metropolitan Council on Housing urging rent strikes “to oppose the decontrol of over-$250 apartments.” There are the handwritten lyrics to Pete Seeger’s “Turn! Turn! Turn!”; a letter from W. E. B Du Bois in 1939 denying he took money from Japan for propagandizing on its behalf; and detailed complaints of police brutality against African-Americans.

Piles of prison correspondence from activists or party members show the human hand behind the rhetoric. “My dear wife Lydia,” Minor writes in pencil after being arrested in 1930 during a labor rally in Union Square in Manhattan. “That little half-hour today seemed the shortest of my whole lifetime. And so indescribably sweet!”

The party started out as an underground revolutionary organization but achieved its greatest successes and popularity in the late 1930s as part of the Popular Front, which it joined at Moscow’s direction, said Maurice Isserman, a historian at Hamilton College who has written several books on American communism. At the same time, he said, some Communist Party members were recruited into an espionage network, which expanded tremendously during World War II, and ultimately infiltrated the team working on the atomic bomb.

Despite its devotion to the Soviet line, the party was still influential in left-wing and labor circles into the first few years of the cold war era. But in 1948 it suffered a triple whammy: the Progressives expelled the Communists; the Communist coup in Czechoslovakia, which was backed by the Soviets, soured many of its members; and the Red Scare ravaged its ranks. Revelations about Stalin’s crimes in 1956 disillusioned many of those who remained and dealt the party a near-fatal blow.

The Communist Party USA contacted Tamiment, which is devoted to the study of labor history and progressive politics, a year ago. Mr. Nash said he was surprised when he got the call. “I didn’t really realize it still existed,” he admitted.

During the summer, Mr. Nash said, he and a group of students scoured the party’s offices on West 23rd Street in Manhattan. They frantically packed up papers before contractors came in to renovate the space, which was being rented out. The donation includes 20,000 books, journals and pamphlets and a million photographs from The Daily Worker’s archives.

Sam Webb, national chairman of the Communist Party USA, said, “We felt that Tamiment could better maintain the collection and provide for a much wider audience.” He said hardly any of the files were reviewed before being given away.

The primary source of American party documents available to the public has been the Library of Congress, which microfilmed a batch of Communist Party USA records in Soviet archives that had been shipped there 50 years earlier for safekeeping. John Earl Haynes, a historian at the Library of Congress who was the first American to examine the Soviet files, said that since N.Y.U. has a copy of the Library of Congress material, “This will give Tamiment the enviable position of being able to offer researchers access to what is in Moscow as well as the new C.P.U.S.A. collection.”

When the collection opened in 2000, the Library of Congress said, “the C.P.U.S.A. has always been a secretive organization,” and “the previous paucity of the archival record has been a major obstacle to scholarship on the history of the American Communist movement,” and a reason for “highly contentious” debates.

That contentiousness continues. In an article on The New Republic Web site last week completely unrelated to the donated archives, Ronald Radosh, a historian, attacked N.Y.U.’s newly created Center for the United States and the Cold War, which is partly sponsored by Tamiment Library. Looking at its spring calendar of public events, he accused it of planning “completely one-sided and partisan events” and said the guests invited to Friday’s gathering are “all, without an exception, either communists or still-believing fellow-travelers.”

Mr. Nash, who is a co-director of the center, characterized Friday as a public relations event, and said overall its programs represent all views.

After flipping through boxes, Mr. Nash moved to a glass case that contained a photograph from the files, a picture of eight American officers who had fought in the Spanish Civil War as part of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. In the next room was Moe Fishman, 92, one of the brigade’s last surviving members, who just happened to be in the library that day for the filming of an unrelated documentary. He had carried over the battalion’s tattered blue flag. Asked if he was in the black-and-white photograph, he slowly walked over, put on his glasses and peered down. “I’m not in that,” he said, “I wasn’t an officer.” But he added, “I have the same one at home.”

Copyright 2007 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Arts, of Tuesday, March 20, 2007.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |