| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted January 7, 2007 |

| Capitalist Punishment | |

| ______________________________________ | |

| P.J. O'Rourke read all 900 pages of 'The | |

| Wealth of Nations' so you don't need to. | |

| ON "THE WEALTH OF NATIONS" | |

| By P.J. O'Rouke | |

| 242 pp. Atlantic Monhtly Press. $21.95 |

| By ALLAN SLOAN |

|

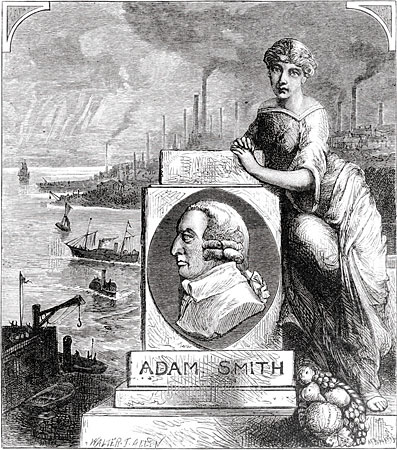

Culver Pictures |

| A woodcut from the 19th century depicts Adam Smith and the Industrial Revolution. |

BEFORE we had radio, telephones, television, the Internet and iPods, we had books. Long books. Complicated books. Books that got read, their length and complexity notwithstanding, because before talk shows and chat rooms, what else was there to do?

Back then, people like Adam Smith wrote long, long, long volumes like “The Wealth of Nations,” which revolutionized economic thought and theory when it was published in 1776. Smith’s treatise, as transformational in its own way as the American Revolution, established the intellectual foundation of capitalism, free markets and individual choice, which are taken as givens in American life the same way that life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness are.

Today, however, almost no one other than the obsessed (or the assigned) is likely to read Smith’s book, which runs more than 900 pages; the author’s convoluted prose makes it seem even longer than that.

So the free market in books has produced Smith-lite: P. J. O’Rourke channeling Adam Smith in a work titled “On ‘The Wealth of Nations.’ ” Think of it as a hardcover blog, in which O’Rourke cites Smith’s essential points, and riffs while preaching Smithian doctrine.

For instance, when O’Rourke discusses one of Smith’s passions, free trade, he notes that “at my house I see a ‘Made in China’ label on everything but the kids and the dogs. And I’m not sure about the kids. They have brown eyes and small noses.” This opus is part of a series its publisher calls Books That Changed the World, a description to which we should append, as O’Rourke says, the further title “Works Which Let’s Admit You’ll Never Read the Whole Of.” Due soon are two other oft-cited but rarely-read-in-full classics: The Koran and Darwin’s “Origin of Species.” It’s a very clever, very market-driven thought: getting to know the classics without having to read them.

The 1937 Modern Library edition of Smith’s work, which O’Rourke cites as his text and I borrowed from my local public library, runs 903 pages, not counting introductions and indexes. Those pages are in small type. Make that very small type.

O’Rourke’s book, by contrast, runs to fewer than 200 pages before appendixes and notes, and has a typeface and layout suitable for modern eyes. And unlike Smith, O’Rourke is a wonderful stylist. Even if you disagree with his conservative political and economic views, as I sometimes do, you’ve got to admire his facility with words.

| This book is like a hardcover blog: O'Rourke riffs as he explains Smith. |

|

|

Susana Raab |

Consider the following passage, in which O’Rourke parodies Smith’s style while explaining why readers aren’t storming bookstores to buy “The Wealth of Nations”: “Pretty soon Smith gets enmeshed in clarifications, intellectually caught out, Dagwood-like, carrying his shoes up the stairs of exegesis at 3 a.m., expounding his head off, while that vexed and querulous spouse, the reader, stands with arms crossed and slipper tapping on the second-floor landing of comprehension.” Add one more phrase, and that sentence would snap in two of its own weight. Which is, of course, the point.

Before we proceed, a confession. I’ve been a business writer since 1969, I specialize in unearthing journalistic nuggets buried in lengthy financial documents that even lawyers find dull — and I’ve never been able to get more than 50 pages into Adam Smith. For several years, I took “The Wealth of Nations” with me on summer vacation, vowing that this time I’d finish it. Alas, I never came close.

But over the years, I’ve read introductions to the book and commentaries about it, listened to discussions of its principles and have even cited some of its points in my own articles. As with the Bible or “Moby-Dick,” you don’t have to be familiar with the entire work in order to grasp its essence.

Smith’s thesis, which still resonates today, is that setting people free to pursue their own self-interest produces a collective result far superior to what you get if you try to impose political or religious diktats. Free people allowed to make free choices in free markets will satisfy their needs (and society’s) far better than any government can. Finally, Smith believed passionately in free trade, both within countries and between them. He felt that allowing people and countries to specialize and to trade freely would produce enormous wealth, because freeing people and nations to do what they do best will produce vastly more wealth than if everyone strives for self-sufficiency.

Now, let’s reduce this theory to microeconomic reality. I can go to my local hardware store, and for $1.79 (plus sales tax), I can purchase a pound of eight-penny nails manufactured in China, thousands of miles from my home. It would take me forever and a day to manufacture my own nails. Instead, I get paid to write articles, which is my specialty, and I can buy a pound of nails for the economic equivalent of a small amount of my time. The store owner, who specializes in helping people like me who’d rather get cheerfulness and good service than go to Home Depot, can use her profit to buy a copy of The New York Times, which helps give the paper the money to pay me for writing about O’Rourke writing about Smith writing about what makes nations wealthy. See? Isn’t that simple?

This all works out fine for O’Rourke and me and whoever is running the nail-making machine in China; he or she is presumably better off doing that than being a peasant farmer or an unemployed urbanite. However, my ability to purchase cheap China-made nails is unlikely to have worked out well for the people who once made nails in the United States. This is Adam Smith’s famous hand of the market at work: it pats specialists like O’Rourke and me on the head, while it gives unemployed blue-collar workers in the Midwest the middle finger. Maybe as a society, the United States saves money by exporting manufacturing jobs and importing so many manufactured goods — but I still have trouble believing that it’s good for us in the long run.

Unlike many free-market devotees, O’Rourke and Smith don’t confuse self-interest with greed: “A recurring lesson in ‘The Wealth of Nations’ is that we shouldn’t get greedy,” O’Rourke writes. Good for them, because while it may seem a subtle point, self-interest and greed are antithetical to each other.

Consider Enron, where cooking the corporate books inflated the stock price, making some book-cookers hugely wealthy. For a while. Ultimately, the scheme came undone, the greedy book-cookers suffered jail sentences, capitalism got a well-deserved black eye. Greed wasn’t good — and it sure wasn’t smart.

I could do without some of O’Rourke’s gratuitous insults of various people, almost all of whom seem to be liberals. Despite this peccadillo — some people might say because of it — this book is well worth reading. You’ll pick up a few good lines, you’ll see a primo stylist at work. And you’ll see why Adam Smith is so often quoted but so rarely read.

Allan Sloan is Wall Street editor of Newsweek.

Copyright 2007 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Book Review, of Sunday, January 7, 2007.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |