White people in the United States die of drug overdoses more often than other ethnic groups. Black people are hit proportionately harder by AIDS, strokes and heart disease. And American Indians are more likely to die in car crashes.

|

By DONALD G. McNEIL Jr. |

Related

-

Health Guides: AIDS | Stroke | Heart Disease

To shed more light on the ills of America’s poor — and occasionally its rich — the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on Thursday released its first report detailing racial disparities in a broad array of health problems.

|

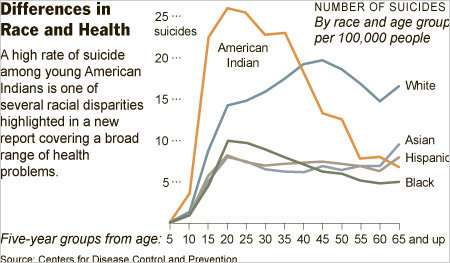

| Differences in Race and Health |

While some are well known, others have had little attention; there were also a few surprises.

The agency did not delve into why suffering is so disproportionate, other than to note the obvious: that the poor, the uninsured and the less educated tend to live shorter, sicker lives. (Some illnesses were also broken down by income level, region, age or sex, but the main focus was on racial differences.)

“Some of the figures, like the suicide rate for young American Indians, are just heartbreaking,” said Dr. Thomas R. Frieden, the C.D.C. director, who ordered the report compiled.

He acted, he said, after promising at his agency’s African American History Month celebration last February that he would do so.

“We wanted to shine a spotlight on the problem and some potential solutions,” he said.

Many of the differences are large and striking:

¶Babies born to black women are up to three times as likely to die in infancy as those born to women of other races.

¶American Indians and Alaska Natives are twice as likely to die in car crashes as any other group.

¶More than 80 percent of all suicides are committed by whites, but young American Indian adults have the highest suicide rates by far — 25 per 100,000 population at age 21, compared with 14 for whites, 10 for blacks and 8 for Asians and Hispanics.

¶Overdoses of prescription drugs now kill more Americans than overdoses of illegal drugs, the opposite of the pattern 20 years ago. Overdose death rates are now higher among whites than blacks; that trend switched in 2002, after doctors began prescribing more powerful painkillers, antidepressants and antipsychotics — more easily obtained by people with health insurance.

¶Blacks die of heart disease much more commonly than whites, and die younger, despite the availability of cheap prevention measures like weight loss, exercise, blood-pressure and cholesterol drugs, and aspirin. The same is true for strokes.

¶High blood pressure is twice as common among blacks as whites, but the group with the least success in controlling it is Mexican-Americans.

¶Compared with whites, blacks have double the rate of “preventable hospitalizations,” which cost about $7 billion a year.

¶People in Utah, Connecticut and North Dakota report the most “healthy days” per month — about 22. People in West Virginia, Kentucky and Tennessee report the fewest, about 17.

¶Blacks, Hispanics and American Indians, whether gay or straight, all have higher rates of new infection with the AIDS virus than whites, and the situation is getting worse for blacks and Indians. Asians have the lowest rate.

¶Binge drinking — defined as five drinks at a sitting for men and four for women — is increasing. In a switch from the norm for health problems, it is more common among the better-educated and more affluent, including college students. But poor people, and especially American Indians, drink much more heavily when on binges.

¶Teenage pregnancy is holding steady or falling for all ethnic groups, but is still three times as common among Hispanic girls as among white girls, and more than twice as common among black girls as among whites.

Dr. Frieden said the purpose of the report was not to nudge the White House or Congress to take any particular action. But said that two relatively new laws had greatly improved the nation’s health and narrowed the racial gaps.

One was the 1994 Vaccines for Children program, which pays for poor children’s immunizations. The second was the earned-income tax credit, which motivates poor people to find jobs. It was first passed by Congress in 1975 but was strengthened several times, and some states and cities have created their own.

Copyright 2011 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, National, of Friday, January 14, 2011.