| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted May 22, 2004 |

Baryshnikov as the Vehicle for Stalinist Memories |

|

| ________________ |

By BRUCE WEBER |

| ________________ |

MINNEAPOLIS, May 19 — In his untidy hotel suite here, Mikhail Baryshnikov stood up, turned an imaginary ignition key fixed to his shirt pocket, and as if his inner engine had just silently kicked in, began to tremble and putt-putt like an idling old jalopy. One leg pumped an invisible clutch and his arm, crooked at the elbow, yanked on a gearshift, oddly stubborn considering it didn't exist. Then, with a smile, Mr. Baryshnikov moved, moonwalking backward.

"Reverse," he said.

Mr. Baryshnikov wasn't just fooling around; he was demonstrating. He's in automotive mode these days in the service of a new theater piece, "Forbidden Christmas, or the Doctor and the Patient," a collaboration with the Georgian writer, director, designer and puppeteer, Rezo Gabriadze.

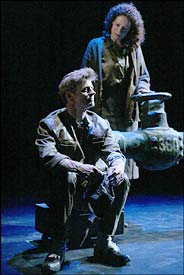

Mr. Gabriadze, a prolific screenwriter and director, best known in this country for two exquisite theater pieces that prominently feature anthropomorphic marionettes — "The Battle of Stalingrad" and "The Autumn of My Springtime" — is this time creating on a larger canvas, with human characters and human-size actors. And with a pitch-perfect bit of casting, it accommodates the boyishness and brilliant body control of Mr. Baryshnikov, 56. He plays Chito, a sweet-tempered madman who believes he is a car. It's easy to conceive of Chito as a puppet infused with breath.

"In Rezo's work, the static object and the human spirit, somehow they interconnect in a very weird way," Mr. Baryshnikov said.

The show, which opened at the Guthrie Theater Lab here on Tuesday, is still being tinkered with. It will appear in a dozen cities, including Charleston, S.C., at the Spoleto Festival, beginning on Thursday, and New York, at the Lincoln Center Festival in July.

Like much of Mr. Gabriadze's work, "Forbidden Christmas" is an ethereal fable drawn from memories of his childhood in Georgia, the Soviet republic where Stalin was raised. Set there in 1952, it's an episodic and elliptical narrative that is sort of a love story, sort of a Christmas story, sort of a history lesson and sort of a memoir, presented with Mr. Gabriadze's signature tone, a wry and gentle melancholy.

It's intended for American audiences, written in Georgian and translated into Russian and then into English; aside from Mr. Baryshnikov, who acknowledges unease delivering lines in English, the cast, which includes Jon DeVries, Luis Perez, Pilar Witherspoon and Yvonne Woods, is American. But language is only one of the storytelling elements here, along with dance (the choreography is by Mr. Perez), music (mostly recordings of Georgian folk tunes), subtly dramatic lighting (by Jennifer Tipton), mime (Charlie Chaplin is a clear influence) and Mr. Gabriadze's backdrop, set, costume and prop designs, which speak with eloquence in a minimalist folk-art mode.

The show begins with a wordless, 20-minute prologue, in which we see Chito as a sailor returning from the sea and witnessing the lover (Ms. Witherspoon) he left behind being married to another man. Despondent, he casts himself into the sea, where he is rescued by an angel (Mr. Perez) — wearing wings and red spats — and left to awaken on the beach. There he discovers a discarded window crank. He kicks it, and it makes the sound of a revving engine. And thus is the automotive fantasy born, and he clings to it as a way of surviving.

The rest takes place seven years later, on Christmas Eve, a holiday celebrated surreptitiously in Stalin's Soviet Union. It takes the form of a journey, in which Chito leads — in his mind, drives — the village's worn-out doctor (Mr. DeVries) to a distant house to treat an ailing little girl. By the journey's end, love and faith have entwined to undim the bleakness of sorrow and socialism.

"Peacefulness, and the understanding there is soul, and there are holidays for the soul," Mr. Gabriadze, 66, said in an interview, when asked what he hoped audiences would take from the show. "Perhaps it's because of my age, but I've become rather moralistic. Please forgive me. And believe me, I do not want to teach anyone anything. I don't like that, and I don't think it's necessary. But I do like when things are not forbidden. And one mystery of life I have solved, which is that it is impossible to forbid spiritual life. Utterly impossible."

Mr. Gabriadze, who spoke in Russian with an interpreter, is a round, grandfatherly, sad-faced man, prone to reflecting on mortality and attracted to small comforts and kindnesses. His wife of 35 years, Ellen Japaridze, who works with him in selecting the music for his shows, hovered about, setting down cheeses, chocolates, fruit and bread and making sure the coffee cups were kept filled. They live in Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia, where he has his own 48-seat theater.

"Everything I write is about Kutaisi," he said, naming the small town of his childhood. "By now the number of my characters is more than the population of my town."

"The city was always squeezed," he said. "Squeezed, by everything imaginable, under socialism. There was a small psychiatric hospital. It couldn't house or provide care for all the patients, and quite a number of mentally sick people wandered around the city. Now, it seems to me, that everyone was envious of these people, because they could say freely what no one else could. And in my country there are strong traditions of relationships with these people."

Chito, from "Forbidden Christmas," had a real-life inspiration, a local man who believed he was a car.

"I do remember this person, the whole city does," he said. "In everyday life, at the table, in conversation, he was a wonderful companion, though our topics of conversation were not that complex."

"When the train would arrive, this man would place himself among taxi drivers and greet the people, the passengers, and he would ask, `Do you need a cab?' He would take your suitcases, you'd follow him, and he'd start the engine and run away. But he would ask your address and he would wait for you at your address. We loved him a lot. He was a very kind man."

Mr. Gabriadze said working with actors rather than puppets was a little thorny, though not because Mr. Baryshnikov and the other actors have their own opinions about things.

"I am a soft director, and Misha, he is very persuasive," he said.

Mr. Baryshnikov said Mr. Gabriadze left him alone to work out his car personification, which he did in a matter of days. But seeking character and not merely anthropomorphic representation, he did some background research in mental illness.

"It's actually quite a common obsession of the last couple of centuries, after the Industrial Revolution, people thinking they are machines, that kind of psychosis where they are trains or airplanes," he said, adding, quite seriously: "The mother-in-law of a very close friend of mine thought she was a helicopter."

The collaboration began two years ago, though each has a different recollection of where it came into being, Mr. Gabriadze saying Paris, Mr. Baryshnikov saying at a backyard barbecue in New York. Mr. Baryshnikov said he suggested they do a small-scale work that would use dance and puppetry, connecting the body language of dancers and marionettes. This excited Mr. Gabriadze, he said, but two months or so later the two spoke and Mr. Gabriadze told him, "Yes, yes, that might work, but I have another idea."

Mr. Baryshnikov said he was not certain that Mr. Gabriadze knew about his work. Mr. Gabriadze scoffed.

"Everyone on the planet knows Baryshnikov," he said.

Ah yes, but did he know about Mr. Baryshnkov's most recent acting work, on "Sex and the City"? Mr. Baryshnikov acknowledged it was not likely to be Mr. Gabriadze's cup of tea.

"Maybe 20 years ago it would have been," Mr. Gabriadze said, with a seemingly rueful smile.

Copyright 2004 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Arts & Ideas, of Saturday, May 22, 2004.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |