| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| More Books and Arts |

| Posted October 28, 2007 |

Attorneys at Politics: Would You Hire One to Represent You? |

|

|

|

By ADAM LIPTAK |

YOU could put together a pretty decent little law firm drawing on just the leading presidential candidates.

It would have two former prosecutors, one intense and the other folksy, a civil litigator from a tony regional firm, a superstar trial lawyer and that scrappy kid from Harvard who gave up the big money to do civil rights work. (O.K., it would also sound like a pitch for a doomed TV show.)

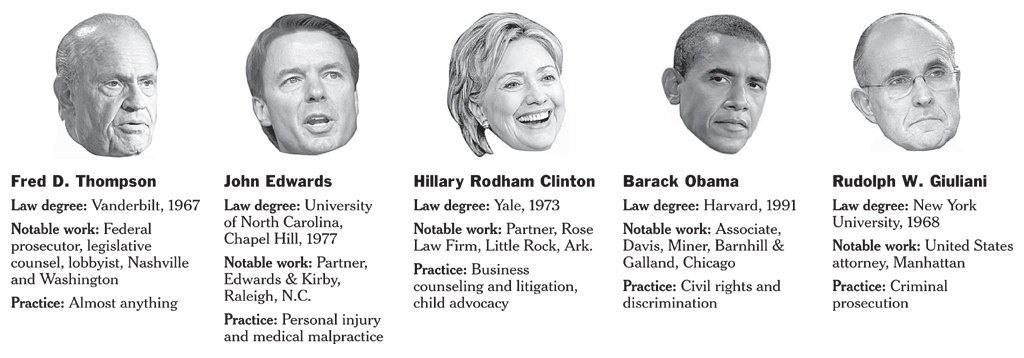

Hillary Rodham Clinton, John Edwards, Rudolph W. Giuliani, Barack Obama, Mitt Romney and Fred D. Thompson all have law degrees, and all but Mr. Romney worked as lawyers for years before entering politics. But the practices they pursued, and how they handled themselves in the process, say something about their values and temperaments, and perhaps provide the outlines of how they would conduct a presidency.

|

The New York Times |

There is certainly something of the commercial litigator’s polish and caution in Mrs. Clinton. Mr. Giuliani’s moral certainty is reflected in his crusades against government corruption, organized crime and insider trading when he was the United States attorney in Manhattan. And Mr. Edwards’s populism and appetite for risk has roots in his enormous success as a lawyer for injured plaintiffs.

But it may be the small moments, the war stories and trial vignettes, that illuminate the candidates most.

The first jury trial Mrs. Clinton handled on her own, for instance, concerned the rear end of a rat in a can of pork and beans. She represented the cannery, and she argued that there had been no real harm, as the plaintiff did not actually eat the rat. “Besides,” she wrote in her autobiography, describing her client’s position, “the rodent parts which had been sterilized might be considered edible in certain parts of the world.”

The jury seemed to buy her argument, more or less, as it awarded only token damages. But no one was particularly happy about the case or her performance. Her former partner, Webster L. Hubbell, told one of her biographers that she was “amazingly nervous” in speaking to the jury.

Mr. Giuliani, in an unusual move, personally handled the 10-week corruption trial of a Bronx political leader in 1986 while he was United States attorney. His work was methodical and not particularly flashy, but he went overboard in his closing argument. “A certain kind of passion threw him off,” the judge told the jurors, saying they should ignore parts of what Mr. Giuliani had said.

Mr. Edwards’s first case as a plaintiffs’ lawyer was for a man who had overdosed on a drug used in alcohol aversion therapy. Just before jurors began deliberations, he got a settlement offer of $750,000, a huge sum in North Carolina in 1984, and one his client was initially eager to accept. But Mr. Edwards, though he was green, liked his chances and rolled the dice. The jury awarded $3.7 million.

“He came over here and ate our lunch,” said O. E. Starnes, who represented a doctor who was a defendant in the case.

As a federal prosecutor in Nashville almost 40 years ago, Mr. Thompson specialized in bank robbery cases. He tried 15 of them, and won 14. But he had mixed feelings about going after people for selling hooch. “My old granddaddy is probably turning over in his grave about my prosecuting moonshiners,” he told The Washington Post in 1985.

Mr. Obama apparently did no trial work, and he chose not to trade his golden credentials, including the presidency of The Harvard Law Review, for a big-money job at a corporate firm. Instead, he worked at a small Chicago civil rights firm, representing people who said they had been discriminated against or denied the right to vote.

“He was a good lawyer working a very hard beat,” said Richard Epstein, a law professor at the University of Chicago, where Mr. Obama taught constitutional law.

But Mr. Obama sometimes seemed ambivalent about the law. In his 1995 memoir, “Dreams From My Father,” he wrote that the law could be “a sort of glorified accounting that serves to regulate the affairs of those who have power — and that all too often seeks to explain, to those who do not, the ultimate wisdom and justness of their condition.”

Twenty-five of the 42 presidents, according to the American Bar Association, have been lawyers, many of them distinguished. Eight, for instance, argued cases before the United States Supreme Court. (William Howard Taft became chief justice.)

But the legal culture has changed in recent years, emphasizing a sort of selection and specialization that would have seemed unfamiliar to John Adams or Abraham Lincoln.

Mr. Edwards, for instance, was known for choosing his cases with care.

“He was very selective,” said James P. Cooney III, who defended a dozen medical malpractice cases brought by Mr. Edwards. “He only took the best cases, and by that I don’t mean the ones with the highest damages. I mean the ones where somebody had done something really bad.”

Mr. Edwards as president could choose some of his fights, but he’d also have to confront crises as they arose.

As a prosecutor, Mr. Giuliani also had great discretion in choosing cases. He was accused of moralizing, relentlessness and a lust for the limelight. Wall Street executives still talk about the colleagues Mr. Giuliani’s office arrested at work and took away in handcuffs.

But no one accused him of playing it safe. The case against a Bronx politician, Stanley M. Friedman, was hardly a sure thing, James B. Stewart wrote in his 1987 book,

“The Prosecutors,” because juries often believe that such cases are motivated by the defendants’ political beliefs rather than conduct. The possibility of losing did not seem to bother Mr. Giuliani. “If you never try to accomplish something, you never fail,” he told Mr. Stewart. “I’d rather fail.”

Mr. Thompson, though best known for playing a lawyer on TV, also had a substantial legal career: as a federal prosecutor during the Nixon administration, as minority counsel for the Watergate committee in the Senate, as a prominent Washington lobbyist and as an adviser to John G. Roberts Jr. during his Supreme Court confirmation process.

As for Mrs. Clinton’s legal skills, critics like to note that she failed the District of Columbia bar exam in 1973, although 551 of 817 applicants passed it, according to Carl Bernstein’s biography, “A Woman in Charge.” Mrs. Clinton, who disclosed the setback in her 2003 memoir, did pass the Arkansas bar exam. If any of the other candidates suffered similar embarrassments, they have not become public.

Mrs. Clinton’s supporters point to her work in children’s rights and her days as a law professor at the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville. But adversaries have been known to offer praise, too.

“She was formidable with juries and very good with judges,” said Philip S. Anderson, a Little Rock lawyer who opposed Mrs. Clinton in three cases. “Her manner was serious and professional. She was there to win. No one in the courtroom had any doubt about that.”

In an otherwise hostile article in the current Atlantic, Caitlin Flanagan wrote that a 1973 essay by Mrs. Clinton in The Harvard Educational Review “is the work of a shrewd, lawyerly mind grappling with a thorny problem and nudging a workable — and humane — solution through the thickets and deadwood of constitutional law.”

Mr. Anderson recalled an anecdote that made the rounds in Arkansas legal circles about Mrs. Clinton’s sense of humor, which is often remarked upon but seldom sighted. Someone at her firm had made off with a slice of pizza she had put aside for later, prompting a firm-wide memo. “Who took the evidence she was saving for a poisoning trial?” it said, Mr. Anderson recalled.

The candidate most enthusiastic about lawyers seems to be Mr. Romney, who has business and law degrees from Harvard but chose business.

Asked at a debate whether he would need Congressional authorization to attack Iranian nuclear sites, he answered that he would consult his lawyers.

That answer did not sit well with John McCain, perhaps the only top-tier candidate without a law degree.

“I don’t think that’s the time to call in the lawyers, when we’re in a national security crisis,” he said at last Sunday’s debate. “Those are the last people I’d call in.”

Copyright 2007 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Week in Review, of Sunday, October 28, 2007.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |