| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted May 18, 2003 |

| |

| As AIDS Ravages Caribbean, Governments Confront Denial | |

By DAVID GONZALEZ |

|

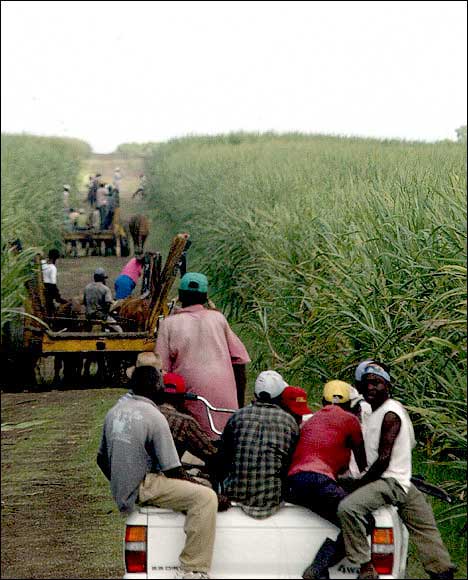

Angel Franco/The New York Times |

| Workers in sugar cane fields in Guaymate, Dominican Republic. AIDS has ravaged bateyes, communities of sugar cane workers of Haitian descent. |

GUAYMATE, Dominican Republic — A ragged and exhausted man summoned his dwindling strength to lift himself off a foam rubber mattress on the floor of a stiflingly hot shack.

"I drink cold water," he said, haltingly, in this town of sugar cane workers, many of Haitian descent. "And that feels hot. Look at my skin. It burns." Advertisement

Since January, he has wasted away from diarrhea. He insists that the local clinic does not know his illness. But a health worker confirms what others only whisper: he is dying from AIDS, one of about half a million people with H.I.V. in the Caribbean, where the infection rate is the highest outside Africa.

While the sheer scale of Africa's epidemic has tended to overshadow the problem here, health experts and political leaders warn of the potential for devastation in a region of small, image-conscious countries that depend on a limited pool of labor and resources, as well as tourism.

Some 40,000 adults and children in the Caribbean are believed to have died of the disease in 2001 alone. It is already the leading cause of death among young men.

"The overall threat is very simple; it is affecting the most productive population in the most productive age group," said Patricio Marquez, a principal health specialist for Latin America and the Caribbean at the World Bank, which is financing a regional response to the disease. "There is the risk that an entire generation could be wiped out."

The epidemic's full extent is obscured by fear, denial, limited treatment and a lack of public health resources. What is certain, however, is that a social and economic catastrophe is imperiling many countries as infections steadily climb and AIDS spreads in the general population.

Some estimates say 2.4 percent of the Caribbean's adult population is infected with human immunodeficiency virus, the virus that causes AIDS, though rates vary widely. The World Bank estimates that in some urban areas as much as 12 percent of adults carry the virus. While Haiti, with an infection rate of more than 6 percent, has gained attention as the region's hardest-hit country, the disease is by no means confined there, officials said.

"It has been compared to a volcano that doesn't stop erupting," Rafael Mazin, a regional adviser on H.I.V. prevention and care for the Pan American Health Organization, said of the epidemic. "It's there. It's there. It's there."

The persistent growth in infections has underscored both the special dangers and challenges that AIDS holds for the region. Migration between islands — and to the United States — is common and helps spread the disease. But the possible isolation of islands under separate governments and different languages remains a huge obstacle to cooperation.

"Being an island is in a sense a figurative way to think about how things have been planned in an insular fashion," said Dr. Arletty Pinel, Latin America portfolio director at the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria.

Political leaders have strongly spoken for prevention, casting AIDS as a development threat that they are trying to confront in order to avoid another Africa-style tragedy. If not, they will end up diverting scant resources to hospitals and clinics that are often hopelessly outmatched by the task of treating the disease.

Antiretroviral drugs for those already infected are almost nonexistent. Money, and often political will, is short. Programs that are effective find themselves quickly overrun. A state-of-the-art treatment program started last year in Barbados, for example, has now drawn more than 600 patients from all over the region.

International donors, meanwhile, have mostly ignored the Caribbean in favor of poorer African nations. Money is now beginning to flow in, including some of the $15 billion pledged by President Bush and earmarked for Haiti and Guyana, another of the region's worst cases.

But some leaders, while welcoming the decision, said the effort was insufficient. "Singling out those two we don't believe is the right approach," said Dr. Denzil Douglas, prime minister of St. Kitts and Nevis, who is considered among the region's most knowledgeable leaders about AIDS.

"Because of the mobility of people within the Caribbean region," he said, "it is to some extent a demonstration of not understanding the nature of the epidemic."

Indeed, although Hispaniola — the island shared by Haiti and the Dominican Republic — accounts for more than 80 percent of Caribbean AIDS cases, the Bush plan provides nothing for Dominican programs. Dominican officials said any fight against the virus must include joint programs with their Haitian counterparts.

"The epidemic in Haiti is a reality, and it is out of control," said Luis Emilio Montalvo, director of the Presidential Commission on AIDS in the Dominican Republic. "It is the poorest country in the hemisphere with AIDS. And we are neighbors." Advertisement

Faced with that threat, Dominican officials have begun to confront the epidemic in ways that donors and policy experts hope could provide a model for the region. In many ways, the country shows both the challenges and advances in the Caribbean.

Dominican officials boast that a recent survey shows infections are 1 percent of the population, or half of what was originally estimated, a decrease they attribute to education and prevention campaigns. But the country needs to tackle the danger posed by migration from Haiti, as well as discrimination, denial and insufficient financing.

"I'm not saying all the barriers have been overcome," Mr. Marquez said. "But it is being discussed in the open and seen as something that requires national attention, because of the risk that it could undermine the whole society and have economic repercussions."

| A Point of Entry |

In a place called Peligro — Danger — the rapid-fire sounds of Creole, the language of Haiti, are more common than Spanish inside the houses of men who earn about $2 for each ton of sugar cane they slash. These bateyes, communities of sugar cane workers of Haitian descent, are among the epidemic's hot spots. "The bateyes have been the point of entry for the disease," said Dr. José Alberto Roman, who works with H.I.V.-positive women in a nonprofit clinic in the nearby southeast coastal town of La Romana and supported by Columbia University. "When I first came here in the 1987, it was rare. Not anymore. Now it is something terrible."

But the epidemic is terrible not merely in its presence, but also in the ignorance that surrounds it and in the near total absence of resources to stem the spread of a disease that does not respect borders.

As it has in their native country, AIDS has ravaged the bateyes, where superstition, poverty and prejudice conspire against hope. The brother of one AIDS patient recently told Sister Anne Liam Lees, a nun who runs several health and nutrition projects, that the man had died from a spell cast by a creditor.

"It's very difficult to confront reality if you do not think this disease exists," Sister Anne said. "Even if you told someone they were H.I.V. positive, they would not believe it. They would just go off and have sex with the first person they saw."

Although several people in Peligro are dying from AIDS, neighbors insist that they do not have a clue. In the neighboring community of Batey 105, residents who are volunteer health educators insist that no one is infected with the virus, a dubious claim.

Hygiene is abysmal in Batey 105, where there is not even a single latrine. One health volunteer attributed an outbreak of fevers to a cold breeze, and many people are sick from diarrhea. Public health workers sometimes come by to hand out antimalaria medicines, when they have them.

If Sandy Senatic Feliz, a volunteer health promoter, is a front-line fighter against AIDS, then her arsenal is woefully inadequate. Every few months, she said, she is given a couple of dozen condoms. She still has five left from her last supply run about half a year ago.

"We haven't had any infections here," she insisted.

Sister Anne doubts that, because there is often a lot of traffic in and out of the bateyes, as many men go looking for construction or other jobs after the cane-cutting season ends. When they return ill, and die, she said, their widows often are forced to pair off with another man to secure a place to live.

"He comes back and spreads the virus without even knowing," she said. "Then she has to find another man because she cannot live alone in the batey. The houses are for the workers in the industry, and a single woman does not work in the industry."

| Working the Clubs |

A syncopated twang blasts through the open-air bar of Jhonnys Patio, as couples embrace and twirl under a flashing rainbow of lights. There is a forced festiveness to the scene, a payday party where men — single and married alike — dance and drink with prostitutes surrounded by murals of nudes.

According to government estimates, as many as 80,000 people earn a living as sex workers in the country, and 4.5 to 13 percent of them may be infected. In Puerto Plata, a north coast resort town, sex is for sale at places from upscale clubs to car washes.

The nonprofit Center for Human Solidarity and Promotion, or Ceprosh, is one of the country's most successful anti-H.I.V. programs and was founded in Puerto Plata in 1989, to help H.I.V.-positive people find new work, and to provide health care and enlist sex workers to teach each other and their clients about protected sex.

Harder to reach are the bisexual gigolos or female massagists who cater to tourists but refuse to consider themselves prostitutes and resist prevention efforts.

The tourist industry has been shy to confront the disease openly for fear of tarnishing its image. But the Punta Cana Group, which developed popular resorts on the island's eastern tip, recently signed an accord with the government — the first of its kind in the Caribbean — to finance H.I.V. awareness programs, as well as to help improve local health facilities.

Other innovative public and private efforts are emerging as well, like that of Ceprosh, whose workers do not use a classroom or clinical terms but take their program to bars and nightclubs using the attitude and language of the street.

At Jhonnys, several woman strut past while an emcee asks which one is clean. Another woman, part of the troupe, strides up to say looks are deceiving.

"How do you keep clean?" she asks rhetorically. "With a condom. Remember, no party without a birthday hat!"

The prostitutes laugh, and even their clients chuckle. The crowd applauds as the women drift out, distributing pamphlets and comic books with graphic depictions of how to prevent AIDS and other infections.

The bar owners — some of whom charge the prostitutes a percentage for cruising for clients — welcome these skits.

"It's good for business, and the client is happier," said José Antonio Acosta, the owner of El Consulado. "You know the problem, so it's good to cooperate."

Women who work the clubs said they almost always used condoms with their clients, but they said sexism prevented them from persuading their husbands or pimps to do the same. Most women in the clubs sell themselves to help rear their children. Some work for pimps who have sex with several women, while others have husbands who have affairs.

Antonio de Moya, an epidemiologist at the Dominican government's AIDS commission, said such relations underscored a cultural contradiction common in the Caribbean, where using a condom with your mistress can be considered the same as being faithful to your wife.

"The paradox of our culture is we have resolved Hamlet's dilemma," Mr. de Moya said. "For us it is to be and not to be. The culture is disjointed. We should be talking about fidelity or prostitution, not both."

The women who work in the industry say condom use is perhaps the best and only hope to slow the epidemic, even if programs like those favored by President Bush emphasize abstinence and fidelity as well.

Josselina Reyes, a quick-witted woman who became a prostitute three years ago when her husband left her and a newborn child, said those options were fantasies.

"Abstinence and fidelity do not exist," she said, laughing. "Neither abstinence nor fidelity will make me any money. Only using a condom."

| More Patients, but Few Tools |

Two solemn relatives prop up a skeletal young man as he shuffles past Dr. Ivelisse Garris's office in the country's only public clinic offering comprehensive services for AIDS patients. Dr. Garris, a compassionate but overworked physician, frowned.

"That patient never should have been sent here," she groused, referring to the man. "In an ideal world he would have been treated closer to his home."

The problem, as on most other islands, is that hospitals and doctors lack the will or the resources to treat H.I.V.-positive patients, bouncing them from clinic to clinic. But the patients keep coming. Even Dr. Garris's clinic in the capital, Santo Domingo, is hardly enough for the 2,000 patients on its rolls, and it is open only on afternoons.

The clinic is not more than a warren of rooms on a second floor that is reached only by stairs, making it a daunting climb for weakened patients. Support-group members, some of whom have lived with the virus for more than a decade, meet regularly to encourage one another. Almost none of them, however, are receiving medication. Advertisement

It was only last year that the government started providing antiretroviral drugs at all, and then only after six patients brought a suit against the government in the Organization of American States' human rights court to make the drugs available.

This year, the Global Fund has approved a $48 million grant to the country, which officials said would allow them to provide medicines for 6,000 people and set up treatment centers. Advocates and aid officials are hopeful that the money will drive what they feel could be a model program.

But for now, medications remain unavailable in many places. Sixty patients at the social security hospital in Santo Domingo — financed by the government, employers and workers — have gone for two months without medications, increasing the risk of drug-resistant viral mutations.

"There is no integrated attention in this country," said Felipa Garcia, director of the country's association for H.I.V.-positive people. "People go to hospitals and don't get the medicines they need. They might get tranquilizers or antibiotics, but that is not real care."

Doctors complain that they have not had deliveries of critical medicines in a program to prevent mother-to-child H.I.V. transmission, a large part of the epidemic's spread. Worse yet, some doctors, fearful of infection, have refused to perform Caesarean sections on H.I.V.-positive women, even though the procedure is crucial to reducing the risk of transmission to the child.

In Puerto Plata, fear of a personal crisis fills the waiting room at the public hospital each morning as pregnant women await the results of mandatory AIDS tests. Every week, a couple of people test positive, prompting denials and anger, doctors said.

On this morning, a woman tethered to an intravenous unit squirmed in her chair, loudly protesting the suggestion that she was H.I.V. positive. Dr. Sonia Ramírez ushered her into a consultation room.

"I'm ready for whatever," she said defiantly, insisting that she was not infected.

Dr. Ramírez gently repeated the test result. She pushed a slip of paper with it across the desk. The woman tore it into small pieces.

"I do not want my mother-in-law to know," the woman said. "My husband said you can live with this virus."

A few blocks away, several dozen members of an H.I.V. and AIDS support group were proving that that was so.

Even given the lack of understanding from employers, and sometimes family and friends, increasingly they and many others are dealing openly with the disease and its effects, waiting for medicines and government resources to catch up.

Not that long ago, they would have been written off for dead. Now, they spoke about the future as a possibility, not a fantasy. Some have small businesses. Others are rearing children.

"This does not take away your dreams," said Elis Consuelo Collado, 31, who received a diagnosis 18 months ago. "You understand life continues."

Copyright 2003 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times of May 18, 2003.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |