| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

More Special Reports |

| Posted August 7, 2009 |

| National |

|

Another Hurdle for the Jobless: Credit Inquiries |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

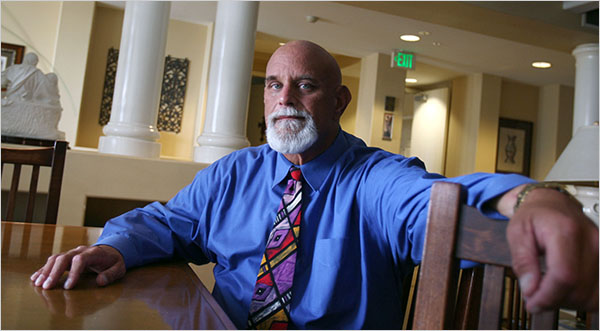

J. EMILIO FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES |

|

| Kevin Palmer, 49, of Santa Ana, Calif., lost a job offer after a credit check revealed a bankruptcy. |

|

By JONATHAN D. GLATER |

|

____________ |

|

|

|

|

| A lawmaker wonders if debt is relevant to skills as a pipefitter. | |

|

____________ |

|

|

|

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |