TAKE an American student and an American teacher who have never been near Africa before, lead them on a crazed “win a trip” journey through five particularly wretched countries, and what do you get?

Well, a few mishaps. There was that angry mob in Mauritania — who would have thought our cameras would upset people that much? And that bull elephant in Niger was equally inhospitable, although the giraffes seemed amiable as they approached to gawk at the strange white humans.

We encountered plenty of heartbreak, like the baby we met in Niger who was going blind from lack of vitamin A. In some places, we felt the gnawing disquiet of insecurity. The rise of banditry and a Qaeda network in West Africa forced us to take an armed escort across one particularly lawless stretch of “highway.”

Yet my travel buddies and I also found something far more significant on our journey: hope. One of the best-kept secrets in the world today can be found in thatched-roof villages like the ones we passed through: Africa appears to be turning around.

After a half-century of underperformance, Africa’s economy is growing significantly faster than America’s or Europe’s. In the last decade, 6 of the 10 fastest growing economies in the world were in sub-Saharan Africa, and, as Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton noted in a recent speech in Ethiopia, that proportion is expected to rise even higher in the next five years. The global economy has turned upside down: Europe risks imploding, while much of Africa is booming.

This was the fifth “win-a-trip contest,” in which I take a student with me on a reporting trip to the developing world. This year I also chose someone from the over-60 crowd. The student winner was Saumya Dave, a medical student from Atlanta, and the older winner was Noreen Connolly, a 66-year-old teacher from a Catholic school in Newark. Neither had ever been to Africa, and they proved wonderful travel companions, cheery even when I explained why not to leave food on a bedside table in a hotel (I once awoke to gaze into the eyes of three rats) or when Saumya came down with a fever that we feared might be malaria (it wasn’t). There was only one experience that my winners balked at: a villager in Burkina Faso asked for Saumya’s hand in marriage.

Our odyssey began in mid-June. Accompanied by an Atlanta photographer and videographer, Thomas Nybo, and armed with everything from satellite phones to mosquito bed nets — all jammed into tiny bags so we wouldn’t have to check luggage — we flew from New York to Casablanca, Morocco.

Morocco is a window into one of the most striking trends in Africa: democratization. The number of electoral democracies in Africa has risen to 18 from 4 in the last decade, according to Freedom House, a nonprofit human rights organization based in Washington. Even in a country like Morocco, which is still a repressive monarchy, easing has occurred. It has freed some political prisoners, moved to strengthen its Parliament a bit and even established a truth and reconciliation commission.

This is how Saumya Dave experienced Morocco:

"On that first morning, we met a reporter who introduced us to protesters who had been beaten and arrested.

"The protesters were young, outspoken, rebellious, headstrong — and endearing. They answered all of our questions with ease, insisting that the efforts already made by the king were superficial, only for show. They were also fearless.

"'We get beaten in school and by our parents all the time,' Imad, one of the protesters said, a grin emerging. 'So being beaten by the police is nothing.'"

From Morocco we flew south to Nouakchott, the sleepy capital of Mauritania. I had been a bit disappointed that no pro-democracy protests in Morocco or Mauritania coincided with our visits — but we did stumble across a melee in Nouakchott. Its target: us.

A Mauritanian host took us to the open fish market, and we strolled through. Suddenly a very large fishmonger grabbed Thomas, outraged by the camera dangling from his neck, and suddenly dozens of others were milling around us and shouting. One of our drivers tried to pull the man off Thomas, and then fists were flying and our driver was suddenly in a headlock. We tried to retreat, and the original troublemaker let go of Thomas long enough to pick up a huge wooden pallet and attempt to smash it down on our vehicles. Fortunately, a policeman rushed over and helped us escape, and we never figured out quite why this tumult had happened. A fluke, I think.

In Nouakchott, we joined forces with Shawn Baker, the Africa head of Helen Keller International, an aid group that does outstanding work on nutrition, blindness and related issues. Shawn, who came to Africa in the 1980s in the Peace Corps and never moved back, showed us one of the most cost-effective interventions to save lives — food fortification.

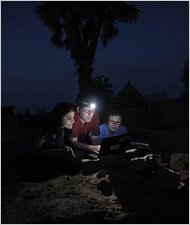

NIGER Technological advances: a thatched hut had solar panels attached to power the light.

These were Noreen Connolly’s reactions that day:

"I never paid attention to the 'fortified with' words on the bag of my sandwich bread. So I was amazed to visit a flour mill in Mauritania and find that food fortification could have a huge impact on the health of a people.

"When people die of hunger-related causes, the problem is often not so much a lack of calories as a lack of micronutrients like iron and zinc. The biggest flour mill in Mauritania, supplying 45 percent of the country’s flour, had just started adding iron, zinc, folic acid and vitamin B12 to its flour — at an added cost of only 1 penny for six baguettes.

"American foreign aid money helped pay the start-up cost of fortification, and the mill will pay all continuing costs. We watched the machines add tiny quantities of the nutrients to sacks of flour — and realized that this mill might end up saving more lives than a hospital."

There has been a backlash in recent years against exaggerated claims about the impact of humanitarian aid. It’s true that aid groups sometimes make the conquest of poverty seem a simpler and more certain endeavor than it is. It’s also true that because of initiatives like food fortification — and vaccinations and vitamin A supplementation and many others — child mortality is tumbling in the developing world. In 1990, 12.4 million children died annually before age 5, according to the World Health Organization. By 2009, despite a significantly larger population, the toll had dropped to 8.1 million, the W.H.O. says.

So, yes, foreign aid has myriad problems, and global poverty is far too persistent — but four million lives saved a year is an extraordinary achievement. And the Obama administration deserves real credit for its Feed the Future aid initiative. This isn’t sexy or well known, but it bolsters African agriculture and nutrition as a cheap and effective way to chip away at global poverty and disease.

With Shawn, we drove south across the Mauritanian desert to Senegal, and then flew the following day to Niger — one of the poorest and most forlorn countries in the world. In the remote town of Dogon Doutchi, near the Nigerian border, we saw with heartbreaking clarity what doctors call severe acute malnutrition.

A 2-year-old child, Alou Muhammad, was lying nearly comatose on a cot in the local hospital, his ribs protruding, receiving fluid from an IV drip. Alou’s left eye had Bitot’s spots — signs of vitamin A deficiency that lead to blindness. At least 250,000 children go blind each year for lack of vitamin A, according to the W.H.O., and half of them die within a year of going blind.

This was Saumya’s report:

"The local hospital was unlike anything I had ever seen. No hand sanitizer dispenser. No faces covered with scrub masks. No supply closet. No physicians streaming down the hallway in stark white coats.

"Alou was in pain, screaming 'Mama!' between sobs. I have seen malnourished children, but this was the first time I could count each rib."

Alou’s family told us that Alou had contracted measles and gone downhill from there. Yet there was also a silver lining: this was the first measles case that the head doctor had seen since arriving at the hospital seven months earlier — and Alou actually came from across the border in Nigeria.

Children in Niger now routinely are vaccinated for measles, and also get vitamin A drops to prevent blindness and death. So even though Niger is one of the world’s poorest countries, it has figured out how to deliver these services to its citizens — while Nigeria, incomparably richer, still allows children like Alou to catch measles and then compels them to receive charity in Niger.

“If Niger can make progress, anybody can,” Shawn told us as we huddled around Alou’s bed. “When I started here in 1985 there were measles outbreaks every year, and some years they would just massacre kids. But that head doctor has been here seven months, and this is the first case she has seen.”

When I first backpacked through West Africa as a law student in 1982, what I found most wrenching were the ubiquitous blind beggars, victims of a disease called river blindness, spread by the bites of black flies. The flies carry parasites that grow into worms whose offspring eat away at the optic nerve and cause blindness, debilitating itching and excruciating pain.

“This was more painful than childbirth,” Fatouma Oumarou, a 70-year-old woman who had gone blind from the ailment, told us when we visited her village. At the peak of the disease, she recalled, much of the land in the area was left fallow because farmers did not dare work the area. In a nearby village, Moli, in a wildlife refuge, people told us that lions had killed a 15-year-old in the fields, but added, “We are more afraid of the black flies than of the lions.”

Yet these days river blindness is gone from this region, thanks partly to heroic work by Jimmy Carter, and to vast contributions of medicine by Merck. I asked villagers if they had ever heard of Jimmy Carter, and they shook their heads doubtfully — but his post-presidency work on global health had transformed their lives.

AIDS still exacts a huge toll on Africa — an additional 1.8 million Africans became infected with H.I.V. in 2009, the last year for which a figure is available — but we saw progress. In Burkina Faso, we visited women who during labor received anti-retrovirals that significantly reduced the risk of mother-to-child transmission. It’s a cheap, simple intervention that avoids the need for lifelong medication for the child.

“There is unprecedented progress in global health,” Michel Kazatchkine, executive director of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, told me. “Things that we would have seen as a dream in 2001 now are achievable objectives. A world of almost no malaria deaths. A world with almost no mother-to-child transmission of H.I.V.”

Partly because Noreen is a teacher, we often stopped in villages and asked about education. Often we ran into children who didn’t go to school at all. But that’s becoming rare, and girls in particular are more likely to attend school now than a decade ago. The United Nations says that primary school enrollment in sub-Saharan Africa has increased five times as quickly since 1999 as it did in the previous decade.

We also asked whether the schools really functioned — it’s common in poor countries for a school building to exist, but for teachers not to show up. We encountered some of that.

We saw many reminders that technology was transforming lives. A generation ago, many in the countryside had to collect water from mud puddles, while now there are covered wells with clean water.

In a few places we saw solar panels used to power electric lights. Roads are improving, and motorcycles and trucks are more common. One result is that when a mother is in difficult or life-threatening labor, she can now sometimes be taken to a hospital in the back of a pickup truck instead of rolled there in a wheelbarrow.

The grandest new technology is the cellphone. “More than 100 people here have cellphones,” one woman told us proudly in her village in Burkina Faso. “There are too many to count.” We asked how many toilets the village had, and she explained that not a single home had yet installed an outhouse.

Why would people prioritize cellphones over toilets? With cellphones, families can find out what market town offers the best price for their goods, or where fertilizer is cheapest. They can save money or transfer it, for cellphones are becoming the banking system for the poor. They can find out where there are jobs, or if contraceptives are finally in stock at the clinic a half-day’s hike away. The villagers were equally intrigued that we thought toilets so crucial, and one explained, “It’s just easier to go in the fields.”

Family planning remains a huge challenge. Only 23 percent of women in sub-Saharan Africa use contraceptives, and we talked to some women who had never even heard of family planning.

“I don’t want any more babies,” Hawa Samaila told us in one village in Niger. “If I can get something to stop getting pregnant, I’d like that.” She had had 12 babies, of whom 6 had died. If African women (who now average more than five children each) had only 2.7 births on average (the rate now in India), Africa would benefit enormously.

Yet family planning remains under-financed, and in a clinic we visited in Mauritania the head nurse, Ould Yatma, said that to receive contraceptives a woman must prove that her husband has consented. “She must bring her husband, or at least bring her husband’s ID card to prove that he agrees.”

Saumya talked to the women about that and this is what she found out:

"While there are women unable to receive contraceptives without a husband’s consent, there are also women educating one another. In Niger, one woman told me that girls are enrolled in literacy classes — which become secure havens for them to discuss issues without men present. One of those topics: family planning.

"Often I met women who were empowered in other ways. In one village, a woman taught Noreen and me how to grind millet, using a huge stick in an oversize mortar. She made it seem effortless and fluid, for women sometimes spend six hours a day grinding grain into flour.

"Then Noreen and I tried. Lift, smash, lift, smash. Within minutes, we were exhausted, our biceps sore. This woman’s 10-year-old daughter outshone us both.

"Before I traveled through these countries, my image of an African woman was of a helpless, downtrodden creature who could do little on her own. I am happy to be proved wrong."

Another obstacle that we encountered firsthand was corruption and suffocating bureaucracy. As we crossed the Mauritania-Senegal border on a ferry, we saw trucks that had been waiting for a month to cross — because of a dispute between government officials on each side. At the Niger-Burkina Faso border, we again saw huge lineups of trucks waiting for customs inspections (which, translated into the local patois, often means payments to officials to avoid an inspection).

African leaders need to promote trade, simplify border crossings, reduce the opportunities for graft and encourage home-grown private business. Niger should be ashamed that its thicket of regulatory requirements make it one of the worst countries in the world in which to do business, according to the World Bank’s terrific Doing Business series. (Niger ranks 173rd out of 183 countries in the 2011 report.)

Another huge burden that we witnessed along much of our journey: civil conflict and insecurity. One of the most robust franchises of Al Qaeda is one we don’t hear much about in America, Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb. It has created a sanctuary for itself in northern Mali — that’s one reason we didn’t try to visit Timbuktu, which is in that region. This branch of Al Qaeda has kidnapped foreigners, apparently for ransom at least as much as for ideological reasons, in a belt from Mauritania to Niger.

In January two Frenchmen were abducted from a bar in the Niger capital, Niamey. A rescue operation led to a firefight in which both men were killed. We heard accounts that Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb was fortifying its army with weapons smuggled from looted Libyan armories.

The group also profits by inviting in cocaine smugglers who fly drugs in from South America and then move them on to Europe.

Noreen reported on the question of terrorism and democracy:

"In Mauritania, we met a pro-democracy writer and activist, Abderrahmane Weddady, who made the case that the autocratic Mauritanian government manipulated American fears of terrorists. The United States supports Mauritania partly because its military fights Al Qaeda — but Mr. Weddady argues that it is the Mauritanian government’s oppression, corruption and economic incompetence that actually drive people to Al Qaeda.

"The United States plays into the hands of Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb when it supports undemocratic governments like his own, he said. 'The real stability is democracy,' Mr. Weddady told us. And yes, it was a little odd to be lectured about the transformative power of democracy — by a Mauritanian."

We had been told in advance that the first stretch of road after we crossed into Burkina Faso might be risky even in daytime — more from banditry than from Al Qaeda — so we arranged a military escort. “There shouldn’t be a problem,” added the person who arranged the armed escorts. “But if there is, get your heads down. They feel that their job is to shoot.”

That’s the kind of Africa story you normally hear — a dash of guns and chaos — and it’s real, but also incomplete. As my win-a-trip winners found on this journey, the poverty is heartbreaking and the insecurity ominous. But the giraffes and villagers alike are hugely welcoming, and the progress is now effervescent. The backdrop is a continent that is chipping away at poverty and disease, while doing a better job of educating its young. Africa seems likely to become a much more important part of the global economy in the 21st century — a place to admire, not to pity.

-

© 2011 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, SundayReview, of July 3, 2011.