| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted July 26, 2003 |

Amazon Indians Honor an Intrepid Spirit |

|

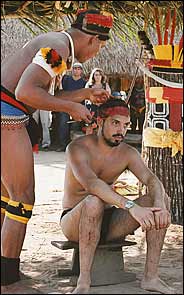

Nicolas Reynard for The New York Times |

| The Son of the Yawalapiti chief groomed Noel, Olando Villas Bôas's younger son. |

By LARRY ROHTER |

YAWALAPITI, Brazil, July 20 — Traveling for hours by boat and on foot, the chiefs, shamans and warriors arrived from all over the southeastern Amazon. For two days they danced, sang, chanted and reminisced around a painted tree trunk, decorated with a feathered headdress, that represented the soul of a recently departed friend.

The trunk was placed in the large open space that is the focus of community life here and implanted almost directly above the burial site of a former tribal leader, so he could help guide the spirit to the "village in the stars."

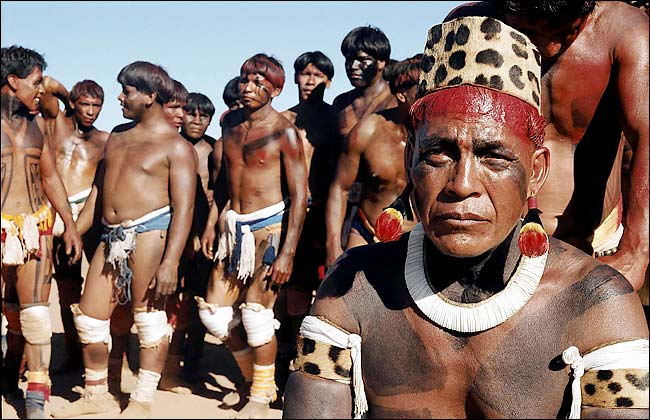

After daubing their bodies and hair with designs in black and red dye, scores of nearly naked men and boys paraded past the totem, whooping and stamping their feet in unison as they moved back and forth.

|

Nicolas Reynard for The New York Times |

Waura men prepared for a ritual dance. |

This elaborate quarup, or traditional Indian ceremony of lamentation for those of noble lineage, has been performed in the splendid isolation of the jungle for time uncounted. The farewell ceremony is normally an insular event performed before members of the community in honor of one of their own.

But the departed friend this time was Orlando Villas Bôas, who died eight months ago at the age of 88 and was buried in São Paulo.

As the eldest survivor of four brothers who devoted their lives to contacting and documenting the native peoples of the Brazilian Amazon and protecting them from the onslaught of modern civilization, he became an especially revered figure here.

"This is the biggest quarup we have ever had, and maybe our last one ever for a white man," said Aritana, 54, the village chief. "It is hard to imagine that any other white man in the future could be a friend of ours as wise and courageous and dedicated as Orlando was."

|

Nicolas Reynard for The New York York Times |

| Men of the Kalapalo tribe did a ritual dance to join the Yawalapiti in honoring friend and protocol. |

Mr. Villas Bôas first ventured into the Amazon as part of an official government expedition 60 years ago this month. Together with his younger brothers, Álvaro, Cláudio and Leonardo, he explored thousands of square miles of unmapped jungle, set up jungle outposts that today are cities or towns, wrote 14 books and helped found and administer the government's National Indian Foundation. As disciples of Marshal Cândido Rondon, modern Brazil's first great Indian expert, the Villas Bôas brothers' philosophy was "Die if necessary, but kill never." They endured countless bouts of malaria, numerous attacks with arrows or spears, and confrontations nearly as fierce with businessmen and politicians eager to open up the Amazon.

But the brothers never wavered, and on this day Mr. Villas Bôas's grateful charges from nearly a dozen tribes here in the Upper Xingu River basin thanked him by consigning his spirit to the heavens.

The brothers' most enduring achievement is probably the creation of the Xingu Indigenous Park. At nearly 11,000 square miles, it is a remote area of jungle and rivers larger than Maryland, home to about 4,400 Indians and closed to outsiders except by the invitation of tribal leaders.

|

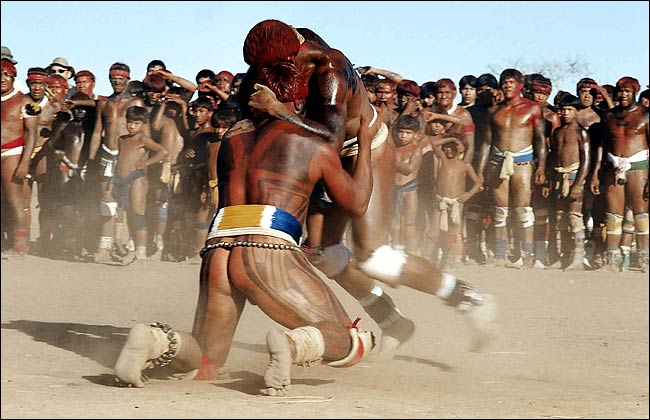

Nicolas Reynard for The New York Times |

Men faced off in a huka-huka, or ritualized wrestling tournament. |

For more than a decade, the brothers fought to obtain the decree setting up the reserve, the first in Latin America. Then they battled 20 more years to have its boundaries legally fixed to protect it from the ranchers, loggers and miners who wanted to see it disappear.

"This park is Orlando's legacy to us, and this quarup is our way of paying him back for the gift he made," said Itiamã, a tribal shaman who believes his age to be 56. "I loved Orlando. After my father died he became like a father to me and always used to tell me that he wanted us to have our own land and to be able to eat what we wanted."

Some anthropologists have criticized the brothers' approach as paternalistic, and the brothers themselves often had mixed feelings about their work. "Each time we contact a tribe we contribute to the destruction of what is most pure in it," Orlando Villas Bôas often said.

Western encroachments are indeed visible here. A painting of Spiderman adorns the entrance to one large thatched-roof lodge where a gas stove is also in use, a photograph of the Eiffel Tower hangs in another and some Indians now travel from village to village on bicycles, and even motorcycles.

But the Indians themselves argue that their situation today would have been much worse had the Villas Bôas brothers not intervened on their behalf. They have been able to retain their original language and religion, and smoked fish and manioc continue to dominate their diet.

"Orlando used to warn us about his concerns for the future, and everything he predicted has come to pass," said Paié, a member of the Kayabi tribe who is the director of the park and came nearly 800 miles from Brasília to attend the ceremony. "Fortunately he trained us and prepared us to deal with the white man and his world."

Many of the 50 or so villages in the reserve would have liked to have had the honor of conducting the ceremony. But the Yawalapiti feel an especially strong bond with the Villas Bôas family, which they credit for their very survival.

When Orlando Villas Bôas first arrived here in the late 1940's, the Yawalapiti had been reduced to fewer than a dozen individuals scattered among several other tribes.

Mr. Villas Bôas brought them together again and encouraged them to marry members of linguistically similar groups, and today 220 people live in the 14 communal lodges that make up this village, with 60 more Yawalapiti at a settlement nearby.

"We owe not just the preservation of our language and our culture to Orlando, but also our very existence today as a people," Aritana, the village chief, said. "He arranged the marriage of my father and my mother, and he saw me born, so he was always a part of the life of the Yawalapiti and my life."

Once the formal ceremony of lamentation concluded, the festivities began. Dozens of men and boys faced off in a huka-huka, or ritualized wrestling tournament, as their mothers, wives and daughters watched and called out encouragement.

The huka-huka has existed for centuries within individual tribes. But the Villas Bôas brothers persuaded the tribes to make the competition regional and transformed it into a substitute for the unceasing wars that had sapped their strength and unity.

"By convincing the tribes to stop their internecine fighting, the Villas Bôas brothers were able to get them to concentrate on the bigger enemy," said John Hemming, the author of "Red Gold," a history of Indians in Latin America, who came here from England for the ceremony at the invitation of Mr. Villas Bôas's family.

Also attending was Orlando's widow, Marina Villas Bôas, who was a 25-year-old nurse when she first arrived here in 1963. She said that from "the very first day," she was swept away by the jungle setting and the man, then nearly twice her age, who dominated it.

"This was where we fell in love and where our sons were conceived and spent the first years of their lives," she said. "So I am of course overcome with emotion to be here again in these circumstances and to see this outpouring of affection and regard from Orlando's friends."

But the region, isolated as it is — a journey of nearly two days by bus, four-wheel drive vehicle and boat from Brasília — is changed from what it was only a generation ago.

Today most of the area around the Xingu park has been deforested. Tribal leaders complain that they now see runoff from pesticides and fertilizer in the headwaters of the Xingu, which lie outside the reserve.

During the quarup, the chiefs and shamans called on Orlando Villas Bôas's two sons, Orlando Jr. and Noel, to continue their father's mission, a challenge the two men said they would accept.

|

Nicolas Reynard for The New York Times |

| Yawalapiti is one of the Indian villages within the Xingu Indigenous park. |

"The destiny of the peoples of the Xingu is still uncertain, because of what is happening around them," said Orlando Villas Bôas Jr., who spent the first four and a half years of his life here. "Brazil may have changed, and the times, too, but in my father's absence someone still needs to work to guarantee that 60 years of effort are not lost."

When Mr. Villas Bôas died last December in the state of São Paulo, where he was born, he was buried with a flood of tributes and a funeral attended by thousands. But Mrs. Villas Bôas said his family regarded the religious ceremony here as being of even greater importance.

"If it had been up to Orlando, this is the place where he would have spent his last day on earth," she said as a pair of shamans sang to his spirit a few feet away. "His work and his memory, his entire life, were here, and we believe, as the Indians do, that once this quarup is over, we will have no more motive to be sad."

Copyright 2003 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, International, of July 26, 2003.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |