|

|

|

|

| Sports News This Month |

|

|

|

|

| Posted March 18, 2008 |

| PORT-AU-PRINCE JOURNAL |

| A Tale of Two Gyms: Building Muscle Worlds Apart |

|

|

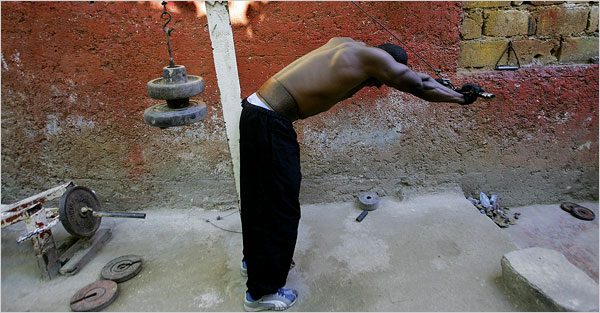

RUTH FREMSON/THE NEW YORK TIMES |

|

| Julien Spencer at the makeshift gym known as the Temple of Pain in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. His machine includes truck parts. |

By MARC LACEY |

PORT-AU-PRINCE, Haiti — The grunts are no different. The clang of the weights sounds pretty much the same as well. And sweat drips off bodies at both the high-end Gold’s Gym in Port-au-Prince’s priciest suburb and at the far more humble open-air workout joint farther down the hill, known by regulars as the Temple of Pain.

But these two gyms might as well be in different worlds, situated as they are on opposite sides of the class divide that has long been such an entrenched part of Haiti.

“Someone at Gold’s would laugh at this place,” said Julien Spencer, 34, a burly bodybuilder who was lifting weights last week at the Temple of Pain, where the machines are made from scrap metal, car batteries and disassembled car engines, a testament to Haitian ingenuity.

“He’d take one look at what we have and walk away shaking his head. He’d say we’re crazy, lifting with all this garbage while they have their fancy machines and air-conditioning.”

Mr. Spencer, who used to work as a trainer at Gold’s, said he still remembered the first time he walk

|

RUTH FRMSON/THE NEW TIMES |

| Mr. Spencer's gym is rudimentary. Few Haitians can afford the nearby Gold's Gym. |

He could not believe all the luxury around him. What particularly caught his eye, he said, were all the electronic exercise machines, with lights and buttons and beepers. None of that is practical in his working-class neighborhood because the electricity goes off all the time.

“Those machines are great there, but I feel more comfortable here,” he said at the open-air workout pit the other day. “I like the vibe. My muscles prefer these homemade machines.”

His remarks are tinged by the fact that he was recently fired from Gold’s, after he argued with the management over his salary. He also had a problem with some of the clients he encountered, not the foreigners so much as the well-heeled Haitians, who he said were used to being waited on hand and foot. When he would remind some Haitians to put the weights away after they were finished, they would sometimes react with scorn. “They’d say, ‘I’m paying you for that,’ ” he said.

And although he finished fourth in a recent bodybuilding competition in Haiti, Mr. Spencer did not dare advise ornery clients on their workout technique. “Rich people think they know more than me about everything,” he said. “They’ll get mad if you point out that they are holding their elbows wrong.”

Technique is one thing that does not change based on the neighborhood — even though the free weights at the Temple of Pain are made from the lead from car batteries, and people have to stand on a chrome fender salvaged from a wrecked car to reach the pull-up bar.

All around the site, which used to be a rat-infested garbage dump before Harres Désiré, a local bodybuilder, cleaned it up, are bits and pieces of salvaged metal that have been forged into machines that do the work of the ones Gold’s purchases at a premium from Cybex International, an American manufacturer of treadmills, steppers, cross-trainers and other exercise machines.

Gold’s sells sports drinks, protein supplements and fashionable exercise outfits to its 400-plus members here in Haiti’s capital. There is nothing to eat or drink at the more humble gym, where the dozen members pay about $8 monthly, about one-eighth the cost of Gold’s but still out of reach for most people in the Juvénat neighborhood.

In upscale Pétionville, Gold’s shares space with a cappuccino shop, a clothing boutique and a wine store, the faint signs — along with a few Domino’s Pizza shops — of the meager foreign investment in Haiti. The talk of the gym in recent months has been the fate of one of its proprietors, who was convicted last year in Florida for drug trafficking.

Although class divisions are firmly drawn here, Port-au-Prince’s power lifters note that income does not matter much when it comes to muscle mass.

“You can have all the money in the world but you can’t buy a body,” Mr. Spencer said, his pockets empty but his arms overflowing from a tight-fitting shirt. “That makes me feel good. If the rich guys could buy fitness, they would buy it. They’d leave us with nothing.”

Robert Volcy, known as Junior, a four-time Mr. Haiti who grew up in a rough downtown neighborhood but now works out at Gold’s, said the class lines of Port-au-Prince meant little to him. He now lives up the hill and works there as a sports promoter, putting on bodybuilding competitions that he says he hopes will demolish the stereotype that all Haitians are scrawny.

“I started out at a little hole-in-the-wall gym,” Mr. Volcy, 33, said, showing off biceps more ample than his questioner’s thigh. “Those humble gyms are where I started, and I still don’t think they are beneath me.”

In fact, Mr. Volcy still goes back to them sometimes when he wants to get away from the networking at Gold’s, where aid workers, diplomats, peacekeepers and elite entrepreneurs exercise and hobnob, and Haiti’s poverty seems far, far away.

Copyright 2008 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, International, of Tuesday, March 18, 2008.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |