| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted November 9, 2003 |

| A Professor Who Refuses |

| To Pull His Punches |

|

|

|

|||

| Susan Ragan for The New New Times |

| By EMILY EAKIN |

BERKELEY, Calif. — In the ring his nickname was Busy Louie. In the classroom, where he spends much more of his time these days, it is easy to see why. Confined by street clothes, his feints and jabs accompanied not by leather gloves but merely by a dwindling piece of chalk and a blackboard eraser, Loïc Wacquant, a professor of sociology at the University of California campus here, all but dances his way through a seminar on the criminal justice system. Advertisement

Twisting, turning, hopping, scribbling, he is in constant motion, demonstrating, for an oblivious audience of a half-dozen sleep-deprived graduate students, the fleet-footed agility that fueled his brief, abortive stint as a pugilist and nearly derailed his academic career.

A slight, excitable Frenchman with a mop of curly brown hair, hyperactive eyebrows and a high-pitched chortle of a laugh, Mr. Wacquant, 43, talks even faster than he moves, and with the same unflagging energy. "It's like drugs," he said of boxing's hold on him. "You have it in your veins."

Weaning himself of the sport, which he took up as a means of gaining access to a poor black neighborhood on Chicago's South Side, has taken him the better part of a decade. He stopped sparring in 1997, and now, after years of delay, his analysis of his days in the ring is finally coming out in print.

Mr. Wacquant (pronounced Vah-KAAHN) calls "Body & Soul: Notebooks of an Apprentice Boxer," which will be published by Oxford University Press later this month (a French edition appeared in 2001), a "sociological-pugilistic Bildungsroman." And for an ethnographic study, it is a remarkably personal work. In novelistic detail it recounts Mr. Wacquant's improbable transformation from winded graduate student to Busy Louie, a 137-pound junior welterweight who manages to pin his opponent on the ropes during the third round at the 1990 Chicago Golden Gloves tournament (though in a controversial decision by the judges, he ends up losing the match):

"I rush at Cooper and attack without letting up. I'm taking a lot of punches but I'm dishing out some of my own in return and the wild shouts of my supporters give me an extra boost of energy. We're both running out of steam and getting tired. Three minutes in the ring is an eternity! Jab, jab, right, double jab, I really am busy — at least I will have earned my ring name!"

"To finish the book was like closing that chapter of my life," Mr. Wacquant said, explaining why it took so long to complete. "It was like burying Busy Louie."

Of course, he is hardly the first intellectual to come under boxing's spell. With "Body & Soul," he joins a long line of writers and philosophers — from Sartre and Heidegger to Arthur Conan Doyle, Ernest Hemingway, Norman Mailer, George Plimpton and, the rare female exception, Joyce Carol Oates — who have tried to capture the brutal sport's allure on paper.

But Mr. Wacquant has serious academic ambitions for the book as well. It is intended not simply as a corrective to the romantic depictions that dominate the literary canon — "Norman Mailer compared two boxers going at it to a metaphysical discussion," he said incredulously — but also as a scholarly manifesto: a model for what ethnography, or field research, should look like.

In this endeavor, however, he may not get much sympathy from colleagues. During the decade it has taken him to write the book, Mr. Wacquant has acquired a reputation as one of his profession's fiercest critics. In more than half a dozen articles and essays, several written in collaboration with his French mentor, the sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, he has subjected his field to withering rebuke.

Among his charges: sociologists ignore racism and the role of the state in creating ghettos; they offer sanitized portraits of the urban poor instead of rigorous analysis of the reasons for their plight; and, worse, their work ends up providing unwitting legitimacy to regressive policies on race and poverty. He has also accused American scholars of cultural imperialism, of importing the peculiar national dynamics of race and racism to their studies of countries like Brazil, where the concepts make little sense.

As Mr. Wacquant put it last year in The American Journal of Sociology in a scathing review of three otherwise well-received urban ethnographies: "U.S. sociology is now tied and party to the ongoing construction of the neoliberal state" and its "punitive management of the poor, on and off the street."

This grim view of government conduct is the subject of his next book, "Deadly Symbiosis," due out in the spring, which argues that American ghettos and prisons have become a single interconnected system for segregating and controlling the poor.

And while his writings have earned him acclaim — his honors include a MacArthur Foundation "genius award" — they have angered many of his colleagues.

"He's upset a lot of people," said William Julius Wilson, a university professor at Harvard who has made extensive studies of Chicago's ghettoes and been a central proponent of the view that racism is increasingly less significant in perpetuating urban poverty than are changes in the global economy and the local job market. He said he had read several chapters of "Deadly Symbiosis" and found much in them brilliant. "However," he added, "as with much of Loïc's work, I'm afraid that many readers will focus on the polemical attacks on the urban poverty literature instead of the powerful and substantive theoretical arguments he makes."

Particularly galling, some scholars say, is that Mr. Wacquant has devoted much of his energy to reprimanding others while, at least until now, producing little fieldwork of his own. "He doesn't go into these communities himself and often criticizes those who do," said Elijah Anderson, Charles and William Day distinguished professor of social sciences at the University of Pennsylvania and the author of "Code of the Street: Decency, Violence, and the Moral Life of the Inner City" (Norton, 1999), one of the ethnographies Mr. Wacquant has attacked. "He'd like to see more militancy in the ghetto, but I'm trying to represent what's going on. If people in the ghetto community espouse a certain conventionality and conservatism, it's not for me to misrepresent."

|

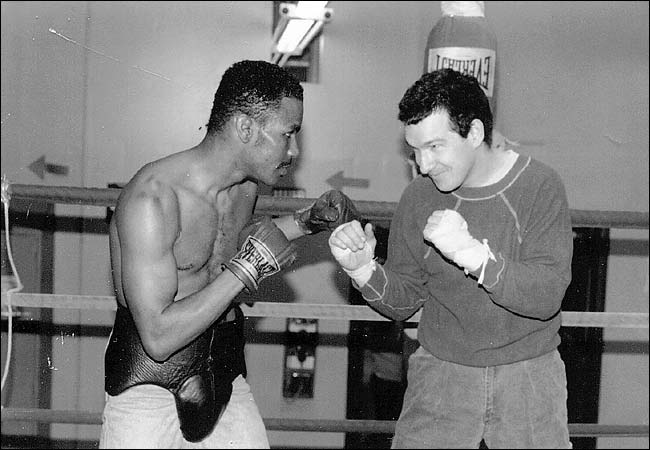

Olivier Hermine, courtesey Loïc Wacquant |

| Loic Wacquant, right, in 1989 with Curtis Strong, the Illinois junior lightweight champion, at Woodlawn Boxing Gym in Chicago. |

Certainly, "Body & Soul," which Mr. Wacquant says is only the first installment of his work on boxing — a second, more ambitious book, "The Passion of the Pugilist," is under way — bears little resemblance to Mr. Anderson's book. Mr. Wacquant calls his approach "carnal sociology" or "ethnography by immersion." The goal, he says, is to convey his subjects' world by experiencing it firsthand — in the case of his boxers, from the point of view of their sweaty, pummeled bodies. It's an ambition, he insists, that represents a radical departure from what passes as ethnography today.

"Either people are portrayed as maximizing computing machines pursuing their interests, or they're portrayed as symbolic animals that manipulate language and obey norms because they're members of a group," Mr. Wacquant said at a cafe near the campus here, throwing up his hands in dismay. "What's missing is that people are first and foremost embodied, carnal beings of blood and flesh who relate to the world in a passionate way."

Comparing himself to Carlos Castaneda, who claimed to have learned the secrets of shamanism and peyote rituals from a Yaqui Indian in the Mexican desert, he said: "I'm a Castaneda who has returned. I think he was right to go off the deep end. But you have to return."

Going off the deep end was not originally part of Mr. Wacquant's plan. When he arrived at the University of Chicago from France in 1985 to earn a Ph.D. in sociology, he already had a dissertation topic in mind: colonialism in New Caledonia, the French-run island in the South Pacific where he had spent the previous two years completing his obligatory military service.

But at Chicago, he soon became distracted by something else: the ghetto. His apartment, the last available unit of graduate student housing that year, was on East 61st Street, two blocks into Woodlawn, a black neighborhood with no high school, movie theater, library or job training center and where a third of the families lived below the federal poverty line.

"I had never seen such scenes of desolation," Mr. Wacquant, who grew up in a tiny village in southern France, recalled. "I remember thinking: It's like Beirut. Or Dresden after the war. It was really a shock."

A friend trying to get in shape took him to the Woodlawn Boys Club, a boxing gym two blocks from Mr. Wacquant's apartment. Though he had been an athlete in high school, enrolling in a special sports track with the intention of becoming a professional tennis player, he had never boxed. But what began merely as a way to get to know some of Woodlawn's residents quickly became an obsession.

Within a year, Mr. Wacquant was spending every afternoon at the club, taking instruction from its coach, sparring with its members and attending fights and tournaments around town. By the spring of 1990, after he narrowly lost the fight at the Chicago Golden Gloves, he was seriously considering giving up his academic career to turn pro.

"When I was on campus, I thought, This is like death," Mr. Wacquant recalled. "Three minutes on campus was too much. I was going to the gym every day for three to five hours at a time."

Mr. Bourdieu begged him to stop. The prestigious Society of Fellows at Harvard awarded him a three-year fellowship, warning him not to incur a brain injury in the meantime. But for the first year and a half, Mr. Wacquant hardly set foot in Cambridge, spending most of his time in Woodlawn instead.

"I was trying to figure out a way so that I could stay in the gym," he said. "It was totally unrealistic. I was sane enough to know that I didn't have a future in boxing. I would have had a lousy record."

Finally, in 1991, Harvard demanded that Mr. Wacquant return. A year later, the Woodlawn Boys Club was closed — and eventually razed — to make way for a parking lot. "I was in a clinical depression for years," Mr. Wacquant said. "It was very difficult for me to get my libido scientifica back."

Still, he emerged from the experience with ample material for his book: more than 3,500 pages of field notes documenting his boxer friends' views on everything from the sport to race, poverty, their families and their neighborhood. (Their casual comments about having done time in prison — "They all thought it was perfectly normal," Mr. Wacquant marveled — became the germ of "Deadly Symbiosis.") But more important, he said, he came away with a visceral understanding of what draws poor black men to the sport.

"It's not the money, not the fame or the possibility of occupational mobility," none of which are likely to be forthcoming, he said. "What binds boxers to their gym is just how gripping it is. It's the sheer sensuous, aesthetic and moral experience of being embedded in that universe."

Mr. Wacquant said he worried that "Body & Soul" would be misunderstood, that its graphic evocations of blood and stench and sweat might strike some scholars as literary embellishments rather than legitimate social science. But the prospect of doing battle with critics doesn't faze him.

"I'm tough," he said with a grin. "I've taken worse in the ring."

Copyright 2003 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Arts & Ideas, of November 8, 2003.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |