| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| More Books and Arts |

| Posted October 16, 2008 |

| A Power That May Not Stay So Super | |

|

|

|

|

|

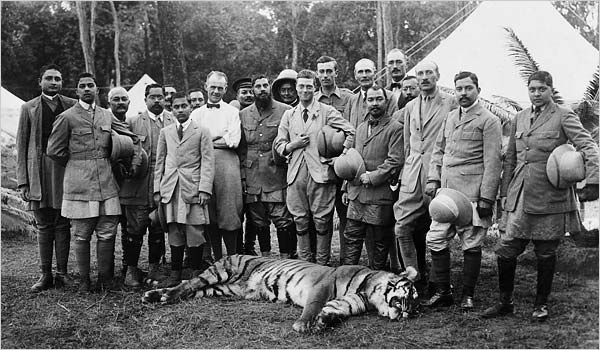

| CENTRAL PRESS/GETTY IMAGES | |

| DECLINE Even as the future King Edward VIII shot a tiger in India in 1921, Britain's empire was overstretched. |

| By DAVID LEONHARDT |

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |