| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted April 2, 2006 |

|

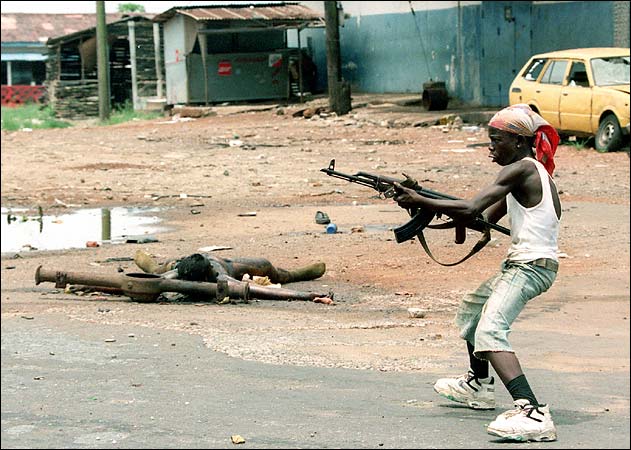

Christophe Simon/Agence France-Press-Getty Images |

| CHILD SOLDIER Eight-year-olds with automatic rifles were fighting for Charles Taylor in Liberia in 1996. |

| A Master Plan Drawn in Blood |

By LYDIA POLGREEN |

FREETOWN, Sierra Leone - ON Christmas Eve, 1989, a small force of about 100 men led by an obscure former Liberian government official crossed the border from Ivory Coast into Nimba County in northern Liberia.

According to local legend, recounted by the Africa scholar Stephen Ellis in his book "The Mask of Anarchy," a baby born in Monrovia, Liberia's capital, miraculously spoke English straight from the womb. It told its mother that a rain of death would fall Christmas Day, and that it did not want to live in such a vicious world, and promptly drew its last breath.

On Dec. 25, in a driving rain, the news that Charles Taylor had attacked Liberia reached Monrovia. As the child predicted, a rain of death soon drenched West Africa. It would last 14 years.

| It wasn't just the violence. Charles Taylor manipulated West African values and smashed taboos. |

On Wednesday, with the apocalyptic deluge at a halt, Mr. Taylor was arrested on the tarmac at Monrovia's airport and whisked immediately here, where he sat in a jail cell at an international court set up to try suspected war criminals in Sierra Leone's brutal, decade-long civil war, which Mr. Taylor is accused of starting and supporting.

In Mr. Taylor's rise and fall, one can glean the story of West Africa, a history of death, turmoil and tragedy. In many ways he was the perfect man to exploit the drawn-out ending of one era — the slow demise of nationalist Big Man politics — and the beginning of another, in which warlords presiding over small, nonideological insurgencies played havoc across much of the region, enriching themselves and laying waste to their homelands.

Indeed, the term Big Man, an overworked cliché of African reportage, seems almost too small in describing Mr. Taylor, and calling him a warlord fails to grasp the breadth of his ambition.

It was his blend of the two roles that proved so diabolical and deadly. By the time he was pushed from power in 2003, more than 300,000 people had died in conflicts he ignited. His forces and allies had looted Liberia and Sierra Leone, and parts of their neighbors, down to the studs. Millions of people had been scattered into half a dozen nations around West Africa. From Liberia alone he is believed to have stolen at least $100 million as president between 1997 and 2003.

"Taylor had a map he carried around with him called Greater Liberia," said Douglas Farah, an analyst and author who has written extensively about Mr. Taylor's links of criminal and terrorist networks. "It included parts of Guinea, diamond fields in Sierra Leone. It wasn't something abstract to him. He had a very clear idea of what he was trying to achieve. He had a grandiose plan, and he almost succeeded."

Mr. Taylor was born outside Monrovia, his mother a housekeeper from the Gola tribe and his father a teacher descended from the returned slaves who founded Liberia.

He was a student activist in the 1970's, railing against the corrupt regime of William Tolbert. Then he went to Bentley College in Massachusetts to study economics. He returned to Liberia in 1980, just in time to see a young army sergeant, Samuel Doe, topple Mr. Tolbert's government, murdering the president.

Mr. Taylor immediately insinuated himself into Mr. Doe's clique, and eventually took control of the government's purchasing arm. He fled back to the United States after falling out with Mr. Doe, taking with him $1 million he allegedly embezzled from the government.

He was jailed in Massachusetts, but escaped in 1985 by sawing through the bars of his jail cell. Once back in Africa, he met with Liberian dissidents in Ghana and then made common cause with revolutionaries in Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast and, most critically, Libya, where Colonel Muammar al-Qaddafi was plotting and supporting a continent-wide revolution. In Libya, he trained in camps that also trained men who would later play starring roles in the great African tragedies of the 1990's; they included Sierra Leone's Foday Sankoh, whose rebel movement would become best known for hacking off the arms and legs of civilians, and the Congo's Laurent Kabila, the central figure in a complex civil war that ultimately killed four million people.

With money and arms from Libya and the political and financial backing of Burkina Faso and Ivory Coast, he crossed into Liberia in December 1989. He had never been a soldier and had only a small force behind him. Still, he managed to wreak havoc on an almost unprecedented scale and dominate much of the region for more than a decade. How did he do it? In part, Mr. Taylor was adept at using and even creating the language of his times. He blended a militant pan-Africanism that called for bloody revolutions against neo-colonialism with a muscular vernacular in which might was unapologetically right. The new pose fit well with the region's mood.

"There is a very strong current within West African diplomacy which basically says you make a deal with the strongest actor because if you don't that person will go back to the bush and fight or otherwise destabilize the situation," said Mike McGovern, an anthropologist with the International Crisis Group who has studied West Africa's conflicts.

|

||

Issouf Sanogo/Agence France-Presse-Getty Images |

||

| NEXT STOP, THE HAGUE? Taylor bridged two violent chapters in Africa's recent past: the fall of nationalist Big Man politics, and the rise of warlordism. |

At the heart of Taylor's horrific genius was an ability to manipulate West Africa's political, social and cultural values, seeming to smash deep taboos while subtly co-opting them for his purposes.

In societies where power had always come with age and young people grew frustrated under the authority of elders, he espoused a smash-and-grab philosophy. Unable to marry without "bride wealth," or dowries, and lacking means to start their own lives until their fathers and uncles died and passed on wealth and land, these young men proved ideal foot soldiers.

His commanders would force boys to kill their parents or other family members, breaking the ultimate taboo, then ply them with methamphetamines, marijuana and other drugs to keep their killing instincts keen. Often their pay came in the form of a license to rape and plunder.

Yet even as he undermined traditional respect for elders, he subtly substituted himself in those elders' place, simultaneously enthralling and enslaving a generation of young boys who slaughtered on his behalf.

This explains his supporters' chilling election campaign cry in 1997: "He killed my ma, he killed my pa, I'll vote for him."

Mr. Taylor also co-opted the secret societies that dominate life in many West African countries, like the Poro hunting society in Liberia. This gave him access to a world of unseen power and allowed him to project an aura of mystery and invincibility. Rumors that he practiced cannibalism, human sacrifice and blood atonement rituals merely added to his mystique.

"He created an aura around him of a man allied to powerful forces you cannot easily comprehend," said Mr. Ellis, the historian.

Mr. Taylor surrounded himself with objects of protection — scepters carved from sacred trees and amulets of invisibility. It was impossible to say whether he really believed in these objects, or merely used them as props.

He used conventional Christianity as well, managing to convince the Rev. Jesse Jackson, former President Jimmy Carter and the evangelist Pat Robertson that he was at heart a good Baptist Christian.

Mr. Taylor also had plenty of money. In his hands, the Liberian state essentially became an adjunct to organized crime and terrorist networks that included Al Qaeda.

"He ran this amazingly complex criminal enterprise where the state could provide critical things like diplomatic passports and airplane registration to a range of criminal networks," Mr. Farah said.

Even before he was elected president in 1997, the vast countryside he controlled, with its rich endowment of diamonds, rubber and timber, generated an estimated $100 million in revenues a year. During his time as president, diplomats sometimes referred to Liberia as "Charles Taylor Inc."

Undoubtedly a greedy man, Mr. Taylor was not, however, stingy with his friends, Mr. Farah said. He was more than willing to share the wealth he looted with the regional powerbrokers who sponsored him, like Libya and Burkina Faso.

But mostly he ruled through fear. Even now, in a jail cell here, he made West Africans tremble. Liberia and Sierra Leone asked that he be transferred to the Hague for trial.

Tamba Ngawucha, whose hands were amputated by rebels backed by Mr. Taylor during the war in Sierra Leone, said he was glad the tyrant arrested. But when asked if he should be tried here, Mr. Ngawucha's eyes widened.

"We don't want any Charles Taylor here," Mr. Ngawucha said, flailing the dimpled stumps where his hands once were for emphasis. "We are too afraid he will hurt us again. We just want peace."

Copyright 2006 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Week in Review, of Sunday, April 2, 2006.

Related text: Film links Aristide to warlords

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |