| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted October 3, 2005 |

| A 'Main Event' in Old New York |

An exibition on the city's slavery may draw crowds or controversy. |

|

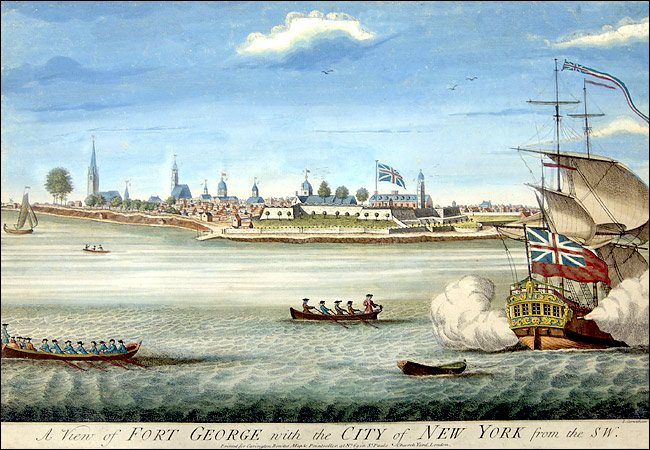

New York Historical Society |

| A view of Fort George in 1732 - More Photos. |

| __________________________ |

By GLENN COLLINS |

__________________________ |

I t is called a trading book. In meticulous, spidery notations, it reveals just how the sloop Rhode Island, owned by Philip Livingston & Sons, New York merchants, traded rum, tobacco and cheese for guns, cloth and ivory in 1749.

Then, along the African coast, it traded those goods for 124 slaves.

The ledger is but one of more than 400 artifacts, documents, paintings and maps in a forthcoming exhibition on slavery at the New-York Historical Society that detail the vital connections between New York and the system of slavery that was an economic engine of the Americas for more than three centuries.

"We all grew up with images of 'Gone With the Wind' and we thought slavery was a Southern institution, but for 200 years slavery was a dominant force in New York," said Richard Rabinowitz, the show's curator.

The $5 million exhibition, "Slavery in New York," will open to the public on Oct. 7. Its story begins in the 1620's and ends on July 5, 1827, when black New Yorkers celebrated emancipation in their state. Late next year, a sequel exhibition, "Commerce and Conscience," will extend the chronicle past the Civil War.

The show is a potentially controversial one for the society, a 201-year-old institution that has stirred debate since it was re-energized by two wealthy, conservative businessmen, Richard Gilder and Lewis E. Lehrman, the forces behind an Alexander Hamilton exhibition that earned mixed reviews from historians last year.

"Many people, blacks as well as whites, have some trouble having the story of slavery told in a major public venue," said James Oliver Horton, the Benjamin Banneker Professor of American Studies and History at George Washington University, who is the exhibition's chief historian. "But we do not have the right not to tell the story."

Spanning 9,000 square feet in 10 galleries, "Slavery" will be half again as large as the Hamilton show. Since the topic "is difficult and sensitive, we must be impeccable historically," said Dr. Louise Mirrer, the society's president.

And so in Gallery 2 there is an original letter from the Dutch West India Company to Peter Stuyvesant authorizing him to sell slaves; he hoped New Amsterdam could be the busiest slave market in North America.

New York's busy economy of importing, shipbuilding, borrowing, lending and insuring was based on a far-flung slave-labor force. Slave ships were good investments, Dr. Horton said, and slaves were owners' annuities - property that could be rented out as a source of income for years. Even newspapers were complicit, making money from ads about auctions and runaways. "Slavery was not a sideshow," Dr. Horton said. "It was the main event."

But the exhibition also highlights overt and covert slave resistance, including coroner records of a 1712 revolt in which 9 whites were killed by 38 slaves.

A key curatorial challenge was that much of the historical evidence speaks solely in the voice of the enslavers, said Dr. Rabinowitz, president of American History Workshop in Brooklyn, an exhibition planning firm. But slaveholders revealed much unintentionally, as in "runaway ads saying such things as 'there are whip marks on his back, but he loves me,' " Dr. Rabinowitz said.

In addition to offering interactive visual presentations about slavery, the exhibition tries to portray the experience of being enslaved - through, for example, the saga of the 20-year-old Deborah Squash, who escaped the employ of George Washington, fleeing to freedom behind British lines.

Last fall's Hamilton show, though trumpeted as a blockbuster, drew smaller crowds than expected and was derided by some historians as a glorification of Hamilton revealing a new conservative bent at the society.

No specific attendance predictions are being offered for "Slavery," except that "we will be mobbed," as Dr. Mirrer put it. The society has already kicked off an $800,000 advertising campaign and plans a robust school-outreach effort, a Web site and a companion book.

The show has been a magnet for money, including a New York City Council grant of $500,000 this year (and $625,000 for next year's installment), as well as $803,000 from the federal Department of Education. The lead sponsor is J. P. Morgan.

Although the society's literature portrays the exhibition as an untold story, "historians have, for decades now, been exploring the impact of slavery on the economic, cultural and racial foundations of the city," said Dr. Mike Wallace, winner of the Pulitzer Prize for history in 1999 for "Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898," written with Dr. Edwin G. Burrows. Dr. Wallace wrote a scathing critique of the Hamilton show in The New York Review of Books, faulting the exhibition for amateurish museumcraft and charging that "the show opts for one-sided, hagiographic boosterism."

The new exhibition is likely to be scrutinized by New York historians as well. "It would be hard not to, given the unfortunate Hamilton show," Dr. Wallace said. "But given who's worked on the slavery exhibition, I'm assuming it is going to be a worthy, and hopefully exciting, enterprise."

The exhibition's potential to enlighten, as well as to offend, is multiracial, said Dr. Howard Dodson, chief of the New York Public Library's Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, which presented a 2000 exhibition on slavery. "With blacks it has been a subject of embarrassment," he explained. "I know that was true with me when I was growing up. And with whites, it's fear of being charged with being guilty because of the sins of the fathers."

Steven H. Jaffe, a former senior projects historian at the society who worked on plans for a show on slavery beginning in 2001 but was dismissed with other staff members after Dr. Mirrer took over, said the society had "gotten really fine scholars on this subject as advisers."

He added: "But the question is how the black communities in and around New York are going to respond when an institution that is perceived as white and patrician starts preening about 'what we're going to tell you about slavery because you don't know it' - when a lot of people in the black community have known this for a long time."

Dr. Horton, a much-praised historian who was the adviser to "Slavery and the Making of America," the recent PBS documentary series, disagreed. "I do not believe that many blacks know this story," he said, adding: "This is not a case of having an elite institution set up an exhibit on slavery without guidance. This exhibit is based on exhaustive research."

His ambitions for the show are large. "This will help to provide historical context for the conversation we need to have about race in this country," he said, adding that it could be a corrective to historical hypocrisy. "The patriots used antislavery rhetoric in reference to America's freedom," he said, "but they were slaveholders - Washington, Jefferson, John Jay, Ben Franklin."

And indeed, Philip Livingston, the owner of the slave-trading sloop whose ledger is part of the exhibition, had a son in the business, also named Philip Livingston, who signed the Declaration of Independence. For New York.

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, TheArts, of Tuesday, September 27, 2005.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |