| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted July 12, 2003 |

|

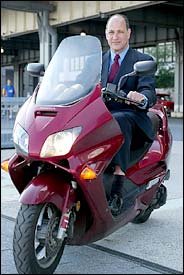

Sara Krulwich |

| Joel Cohen, lawyer and author, favors a red scooter for his urban treks. |

A Lawyer's Mind Channels Moses |

By RALPH BLUMENTHAL |

THE book jacket is enough to invite double takes — "Moses: A Memoir." When did Moses find time to jot down his thoughts? While fleeing Egypt with the Israelites? Between trips up Mount Sinai to receive God's commandments and law? Then again, he did wander in the desert for 40 years and live to be 120. Advertisement

But the prophet's voice that fills this unauthorized sixth book of Moses, now reaching stores and online booksellers, is imagined by Joel Cohen, a 59-year-old observant Jew, a partner at the law firm of Stroock & Stroock & Levan and former federal prosecutor.

Unlike the Moses in the Bible, who carried modesty to a fault and shunned introspection, Mr. Cohen's Moses has a lawyer's analytical turn of mind and a way of posing difficult questions — qualities well-served by the vigorous cover portrait, circa 1600, by the Italian master Guido Reni.

The venture is striking for its ecumenism. The subject is Judaism's towering liberator and lawgiver destined to implement God's covenant with Abraham of 400 years before, but "Moses: A Memoir" is published by the Paulist Press, the venerable Catholic publishing house.

"We published it ultimately because it's a very good book," said the Rev. Lawrence Boadt, the editor, a Paulist priest and an Old Testament scholar. "We get a lot of Jewish manuscripts, and we often say, `This is too Jewish for a Catholic audience.' " But Moses is a venerated prophet for Christians too, he said, and the book promised to attract a cross audience. Indeed, it has reached No. 9 on the Catholic Book Publishers Association bestseller list. The initial print run was 10,000 copies.

It was at the priest's behest, too, that Mr. Cohen sprinkled the 155-page book with citations from the Bible and commentaries — including passages from the New Testament — as familiar touchstones for readers.

At the risk of being condemned for his audacity, Mr. Cohen, who likes to zip around town on a red Honda scooter, writes that as a believer he accepts the Five Books of Moses as the word of God. But they go only so far: "The details, the inner thinking of the human protagonists, were left on the cutting room floor of the Creator," he said. So he took on the task of recreating Moses as he looks back on a life of faith and struggle and of evaluating him with a practiced lawyerly eye: "He won his case big at the Golden Calf."

"Moses never complains," Mr. Cohen said during a kosher lunch (fruit plate, muffin, raspberry Snapple) at the Center for Jewish History on West 16th Street, where he had done some of his research. So, in the book he does some of the arguing for Moses, as when Moses, calling himself "a faithless, whining wretch," gives vent to his deathbed anguish at being barred from the promised land: "Still, were my sins so horrific? Did I rob? Did I covet women? Did I swear falsely?"

Ordained to die with an unmarked grave site atop Mount Nebo to keep the Israelites from erecting yet another idolatrous shrine, Mr. Cohen's Moses puzzles the mystery of his punishment. Did God deny him a final triumphant entry into Canaan because it had become too important to him? Had he lacked faith? Was God sending a stern message to the Israelites? There is an answer, but it comes only later.

Looking back on his life, Moses struggles to explain his killing of an overseer in the Hebrew slave pits of Pharaoh's Egypt. Was it an effort to escape his privileged life with the masters and identify with his subjugated brethren? Or a descent into barbarity? After that, God didn't need to banish him. He banished himself: "I became a fugitive."

At the Midianite camp, he meets Jethro's daughter Zipporah. "She stupified me with her dark-skinned beauty and dazzled me with her gracious spirit." (Mr. Cohen dedicates his book in part to his wife, Eileen Frank, "the dark-skinned beauty who, like Zipporah, always inspires.") When God first appears to him in a burning bush, Moses wonders whether Zipporah's wine has turned sour, causing him to hallucinate. He concludes that the flame was indeed there but "only for one willing to see it."

Led by God to liberate the Israelites, he wonders why God didn't do a better job of storytelling in Exodus. There had to be more agony than we're told over the tortures of the 10 plagues. But the account was flat, like so many other dramatic episodes in the Bible. "The lesson is that miracles exist only for those who allow themselves to observe them," Moses concludes.

There is mystery too, Moses finds, in the Ten Pronouncements (only nine were commandments, the first was more of a declaration). Where was the fine print, the nuances? What if you just lusted in your heart? And what should he wish for his brother, Aaron, the head priest, who had already violated the first pronouncement by erecting a huge golden idol? That he be struck dead? Instead, Moses decrees a massacre of the 3,000 idolators: "Every man kill his brother." Later, in another brutal cleansing, he watches God swallow up the rebellious followers of the renegade tribesman Korah. Similarly, the generations that were born in Egypt have to die out before the young remnant can claim the promised land. There are no easy decisions, just bad options and worse options.

In the end, Mr. Cohen's Moses gains his tragic insight. He is like the pilot of a ship that founders at sea. The men are lost and he alone survives. But he is not to be celebrated, rather doomed to walk the earth in misery. So, too, must Moses be denied his promised land. He dies on Mount Nebo with God's warm breath upon him "like a tender kiss from my beloved."

Mr. Cohen grew up in Brooklyn with a good grounding in the Books of Moses. His father, a lawyer, and his mother, were observant Jews, and he attended yeshivas, or religious schools. But he did not get to see Cecil B. DeMille's epic "Ten Commandments" when it came out, in 1956. "The rabbi prohibited us," he recalled over lunch. "He thought the movie created a particular Moses that wouldn't let you see anymore the biblical Moses."

Mr. Cohen went on to attend Brooklyn College and the New York University School of Law. He investigated corruption in the New York City criminal justice system for the special state prosecutor Maurice H. Nadjari in the 1970's, and from 1977 to 1983 served as a supervising prosecutor in the Brooklyn office of the United States Attorney for the Eastern District of New York. He then went into white collar criminal law practice and joined Stroock in 1985.

His recent clients, whom he would not discuss, include Frank E. Walsh Jr., a former independent director of the scandal-plagued manufacturing conglomerate Tyco International, who pleaded guilty last December to securities fraud; he avoided prison by agreeing to repay the money and a $2.5 million fine. Mr. Cohen has also represented Robert Durst, of the real-estate development family, whom the police wanted to question about the disappearance of his first, wife, Kathleen, in 1982; he has not been charged in this matter.

Mr. Cohen is a relentless contributor to legal journals, the list of his published articles since 1970 running to 13 pages of his résumé. He also moderates legal forums, like one last February at the Fifth Avenue Synagogue on 62nd Street on "The Religious Felon: A Paradox?" The event, examining cases of pious people who commit crimes, included his friend and fellow criminal lawyer Ivan S. Fisher; Mr. Fisher's friend Norman Mailer; and the synagogue's rabbi, Sol Roth.

The Moses book, Mr. Cohen said, grew out of a discussion several years ago with Mr. Fisher about Mr. Mailer's 1997 autobiography of Jesus, "The Gospel According to the Son," a serious effort to tell Jesus's story from his own point of view. Mr. Cohen said that got him thinking. He went to his rabbi, Israel Wohlgelernter of Young Israel of Fifth Avenue, on West 16th Street, and suggested, "Why don't you do the same thing with Moses?"

"Why don't you?" the rabbi said.

Copyright 2003 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Arts & Ideas, of July 12, 2003.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |