| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

More Special Reports |

| Posted October 19, 2007 |

|

PHOTOGRAPHS BY SCOTT DALTON FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES |

| A dance troupe performed at an annual drum festival in San Basilio de Palenque, Colombia. The villagers speak what is thought to be the only Spanish-based Creole in Latin America. |

| SAN BASILIO DE PALENQUE JOURNAL |

| A Language, Not Quite Spanish, With African Echoes |

By SIMON ROMERO |

SAN BASILIO DE PALENQUE, Colombia — The residents of this village, founded centuries ago by runaway slaves in the jungle of northern Colombia, eke out their survival from plots of manioc. Pigs wander through dirt roads. The occasional soldier on patrol peeks into houses made of straw, mud and cow dung.

On the surface it resembles any other impoverished Colombian village. But when adults here speak with one another, their language draws inspiration from as far away as the Congo River Basin in Africa. This peculiar speech has astonished linguists since they began studying it several decades ago.

The language is known up and down Colombia’s Caribbean coast as Palenquero and here simply as “lengua” — tongue. Theories about its origins vary, but one thing is certain: it survived for centuries in this small community, which is now struggling to keep it from perishing.

Today, fewer than half of the community’s 3,000 residents actively speak Palenquero, though many children and young adults can understand it and pronounce some phrases.

|

| A student wrote an assignment on the board during a language class. The classes are part of an effort to preserve the unique local language, called Palenque. |

“Palenge a senda tielan ngombe ri nduse i betuaya,” Sebastián Salgado, 37, a teacher at the public school here, said before a classroom of teenage students on a recent Tuesday morning. (The sentence roughly translates as,

“Palenque is the land of cattle, sweets and basic staples.”) Palenquero is thought to be the only Spanish-based Creole language in Latin America. But its grammar is so different that Spanish speakers can understand almost nothing of it. Its closest relative may be Papiamento, spoken on the Caribbean islands of Aruba, Bonaire and Curaçao, which draws largely from Portuguese, Spanish and Dutch, linguists say. It is spoken only in this village and a handful of neighborhoods in cities where workers have migrated.

The survival of Palenquero points to the extraordinary resilience of San Basilio de Palenque, part of whose very name — Palenque — is the Spanish word for a fortified village of runaway slaves. Different from dozens of other palenques that were vanquished, this community has successfully fended off threats to its existence to this day.

Colonial references to its origins are scarce, but historians say that San Basilio de Palenque was probably settled sometime after revolts led by Benkos Biohó, a 17th-century African resistance leader who organized guerrilla attacks on the nearby port of Cartagena with fighters armed with stolen blunderbusses.

And while English-, French- and Dutch-based Creole languages are found in the Caribbean, the survival of one in the interior of Colombia has led some scholars to theorize that Palenquero may be the last remnant of a Spanish-based lingua franca once used widely by slaves throughout Latin America.

Palenquero was strongly influenced by the Kikongo language of Congo and Angola, and by Portuguese, the language of traders who brought African slaves to Cartagena in the 17th century. Kikongo-derived words like ngombe (cattle) and ngubá (peanut) remain in use here today.

|

THE NEW YORK TIMES |

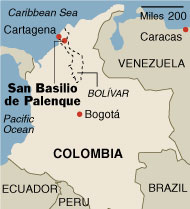

| San Basilio de Palenque was founded by runaway slaves. |

Advocates for keeping Palenquero alive face an uphill struggle. The isolation that once shielded the language from the outside world has come to an end. Once three days by mule to the coast, the journey to Cartagena now takes two hours by bus on a bumpy dirt road.

Electricity arrived in the 1970s as a government gift in recognition of Antonio Cervantes, better known as Kid Pambelé, a Colombian world boxing titleholder who was born here. With electricity came radio and television. The schoolhouse, named in honor of Biohó, has an Internet connection now.

But Palenqueros, as the community’s residents call themselves, say the biggest threat to their language’s survival comes from direct contact with outsiders. Many here have had to venture to nearby banana plantations or cities for work, and then found themselves ostracized because of the way they spoke.

“We were subject to scorn because of our tongue,” said Concepción Hernández Navarro, 72, who survives by farming yams, peanuts and corn.

Only two of Ms. Hernández’s eight children live here; five are in Cartagena and one moved as far away as Caracas, drawn by Venezuela’s oil boom. “We have always been poor here,” she said in an interview in front of her modest house, “but our poverty has grown worse.”

If there is one blessing to this impoverishment, it may be that Colombia’s long internal war has largely been fought over spoils in other places, allowing teachers here to toil uninterrupted at reviving Palenquero since classes were introduced in the late 1980s.

Undaunted by the prospect of Palenquero’s disappearing after centuries of use, Rutsely Simarra Obeso, a linguist who was born here and lives in Cartagena, is compiling a lexicon. Others are assembling a dictionary of Palenquero to be used in the school.

The defenders of Palenquero view their struggle as a continuation of other battles. “Our ancestors survived capture in Africa, the passage by ship to Cartagena and were strong enough to escape and live on their own for centuries,” said Mr. Salgado, the schoolteacher.

“We are the strongest of the strongest,” he continued. “No matter what happens, our language will live on within us.”

Copyright 2007 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, International, of Thursday, October 18, 2007.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |