|

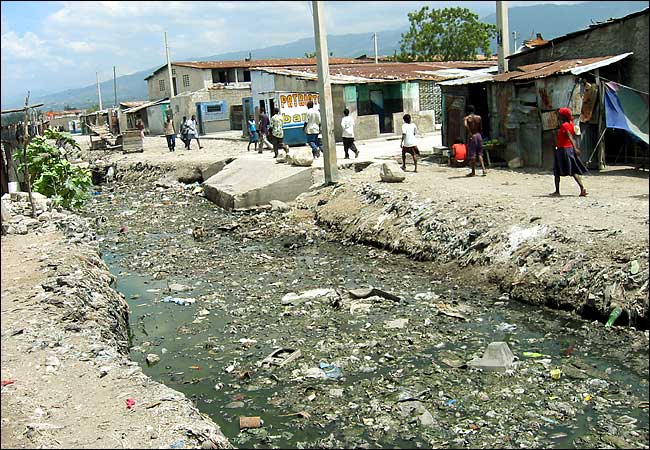

| Neal Gettinger / A sewage-filled ditch in Cité Soleil, a sprawling slum on the outskirts of Port-au-Prince, Haiti. A gun battle on July 6 has increased tensions. Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company |

| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

More Special Reports |

| Posted August 29, 2005 |

A Haitian Slum's Anger Imperils Election Hopes |

|

| Neal Gettinger / A sewage-filled ditch in Cité Soleil, a sprawling slum on the outskirts of Port-au-Prince, Haiti. A gun battle on July 6 has increased tensions. Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company |

By WALT BOGDANICH AND JENNY NORDBERG |

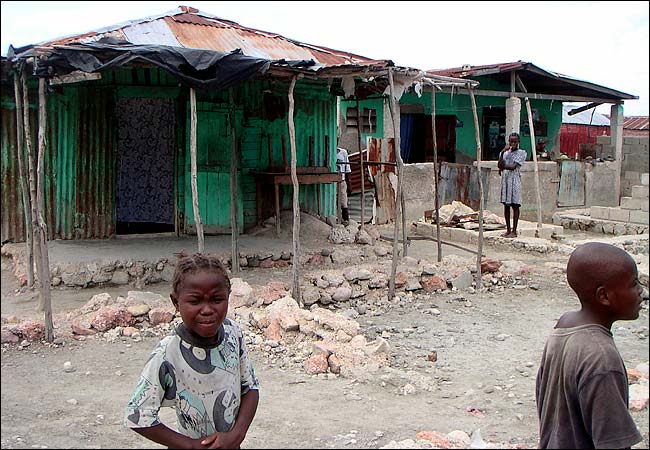

PORT-AU-PRINCE, Haiti - Sitting at the gateway of the nation's capital, Cité Soleil is a broiling slum of shacks, dust and ditches filled with human waste. It is home to several hundred thousand people who now live with virtually no government services, no police and only an occasional helping hand from international aid groups.

Yet, with the first round of national elections now scheduled for Nov. 13, what happens in Cité Soleil is increasingly important to the world beyond its squalor. Not only does it have one of the biggest blocs of potential voters - many of whom back Jean-Bertrand Aristide, the ousted president - but it also can generate the kind of violence that could disrupt those elections.

| _________________ |

| Residents Could Use Votes or Violence to Sway Poll |

| _________________ |

For United Nations peacekeeping forces, bringing some semblance of order to Cité Soleil and giving its residents a chance to vote in the elections are seen as important steps in establishing a new, credible government in Haiti.

But while United Nations troops have managed to set up command posts in sections of other poor, violent neighborhoods like Bel Air, large parts of Cité Soleil - the country's biggest slum - remain all but impenetrable .

Cité Soleil is now so foreboding that the international peacekeepers, who wear flak jackets and drive armored personnel carriers, conduct no regular patrols in its densely populated neighborhoods. In their last operation, about 400 United Nations troops entered the slum on July 6 and ended up in a five-hour gun battle with gangs who control the area.

Numerous residents were wounded in the cross-fire, and the incident has further embittered many Aristide supporters as elections near.

"Cité Soleil is symbolic of Haiti's potential of creating a new society that is inclusive rather than exclusive," said Robert Maguire, director of international affairs programs at Trinity University in Washington, D.C., and an expert on Haiti. He added that if Cité Soleil is not part of the voting, "I think the elections will be far less than credible."

Gangs regularly monitor who comes and goes on the only two roads leading into the slum, according to relief workers. [On Aug. 24, a Peruvian soldier stationed on the edge of Cité Soleil was shot by a sniper, according to a spokesman for the United Nations force.]

On a recent mid-August day, local political leaders escorted reporters for The New York Times into Cité Soleil, a largely treeless tract of tin huts and crumbling cinderblock. With no running water, drainage ditches are a rancid mix of human waste and garbage that must be crossed by walking on stones or on a narrow bridge with missing planks.

The neighborhood leaders, all members of Fanmi Lavalas, the political party founded by Mr. Aristide, wanted reporters to see what they say is evidence of indiscriminate killings by peacekeeping troops during the July 6 raid. These leaders blame the international community, particularly the United States, for Mr. Aristide's departure and for setting up an interim government that is now supported by the United Nations.

According to the United Nations account of the raid, soldiers responded to months of violence in Cité Soleil - much of it directed at its own residents - by staging a predawn assault with armored vehicles and helicopters. Their prime target: Emmanuel Wilmer, a gang leader also known as Dread Wilmé. Mr. Wilmer and other gang members were killed in the ensuing battle.

In a cinderblock hut, baking in Cité Soleil's midday heat, 13 residents of the neighborhood, brought together by the political leaders, squeezed around a small wooden bench to tell a different story. There, they laid out seven pictures of people, including women and children, who they said had been killed by United Nations troops.

"Here are the ones we had a chance to photograph before the dogs ate them," said René Momplaisir, a local Fanmi Lavalas leader. Many victims appeared to have been shot in the head, though who fired the bullets - United Nations troops or gang members - could not be independently verified.

"Why do people die like that?" Mr. Momplaisir said. "It's because there's no justice in Haiti."

John Joël Joseph, a Fanmi Lavalas leader, said dozens of residents were killed or wounded during the raid. "This is an extremely sad day," he said.

United Nations officials said in a statement that an undetermined number of innocent bystanders "may have been injured or even killed." They also cited "unconfirmed but numerous reports" that gangs killed residents after the troops left.

During the recent visit, several residents, including three children, showed reporters what they said were wounds inflicted by peacekeeping troops. Adeline Pierre, 28, said she had been pregnant and lost her unborn baby after being shot.

They're on the ground and they're in the air, coming after us," she said. "I was standing in front of my house and I felt all of a sudden something hit my stomach," Ms. Pierre said.

Olivia Gayraud, the administrator of a free hospital run by Doctors Without Borders, about a 20-minute drive from Cité Soleil, said doctors there treated 27 gunshot victims from the raid, but that the number of wounded was very likely to have been higher. Most were children and women, Ms. Gayraud said, including a woman in her 28th week of pregnancy who lost her baby. The hospital declined to identify the woman because of privacy concerns.

Dr. Christophe Fournier, at Doctors Without Borders in New York, said the clinic in Haiti had treated 1,132 gunshot victims since it opened in December. Most appear to be victims of gang violence. But according to Ms. Gayraud, most patients wounded July 6 said they had been shot by international peacekeepers.

Juan Gabriel Valdes, who oversees United Nations operation in Haiti, acknowledged in an interview that some bystanders were shot during the raid, but he also accused gang members of using women and children as shields.

The attack was necessary, Mr. Valdes explained, "because this gang was threatening the whole city and was attacking innocent people." He said the operation took weeks to plan, and that it was changed three times to try to minimize non-gang casualties.

United Nations officials said they are investigating the events of July 6, but declined to provide further details.

Mr. Valdes said Cité Soleil has been particularly difficult to penetrate because it is so big, the gangs so strong and living conditions so wretched. He also said he lacks commando troops trained and equipped for urban warfare.

The Fanmi Lavalas leaders who showed reporters around said they do not believe in violence and they portrayed Mr. Wilmer as someone who tried to protect neighborhood residents from a gang that threatened them. Human rights workers say that some gangs - and there are a variety in Cité Soleil - are terrorizing residents, and that rapes are a particular problem.

|

| Jenny Nordberg / Children in Cité Soleil, which has virtually no government services, no police and only an occasional hand from international aid groups. Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company |

According to a report released this year by the University of Miami School of Law, some violence in Cité Soleil had been stoked by Haitian business interests who backed an anti-Aristide gang. The leader of that gang was later killed.

Mr. Valdes said the country was awash in guns, some distributed by political parties and even by "some members of the higher social sectors in this country." He added, "The abundance of weapons in this country is a sickness of the whole Haitian society."

When reporters from The Times walked through Cité Soleil, no weapons were seen nor gunfire heard, which was very unusual, according to a human rights worker who regularly visits the community. The worker speculated that political leaders had helped to ensure that guns were not visible during the visit.

[United Nations troops stationed on the outskirts of Cité Soleil say they are fired on daily from inside the neighborhood, which has kept them from conducting regular operations inside, Col. El Ouafi Boulbars, a spokesman for the United Nations military force in Haiti, said in an interview in late August. "We can do them but the problem is the collateral damage," he said.]

That violence is also hampering election preparations in Cité Soleil.

[Gérard Le Chevallier, the United Nations chief electoral officer in Haiti, said in late August that a voter registration center has been open for several weeks in an industrial area on the edge of Cité Soleil, but that is not where most people live. Mr. Le Chevallier said a second center opened Aug. 25, in a more populated area of the slum, and workers in one factory have also been registered.]

Registration ends Sept. 15 for national elections this fall.

Political leaders in Cité Soleil are deeply skeptical of elections, having watched as Mr. Aristide, who twice took office in elections, was twice removed - by a coup in 1991 and again in 2004, when, after widespread protests and an armed rebellion, the United States flew him out of the country. He is now in exile in South Africa.

In addition, members of his political party, Fanmi Lavalas, have been jailed under the interim government, sometimes without due process, according to the United Nations. The most prominent of these prisoners is Yvon Neptune, Mr. Aristide's former prime minister.

"Fanmi Lavalas has always said that there's only one way to get power in this country and that's the way of elections," said Mr. Joseph, the party official. "But how can we talk about elections when all of our party officials are in prison?"

Other members of Mr. Aristide's party - who call themselves simply Lavalas - support the elections and are running for government posts.

As the international community tries to assert its authority in Cité Soleil, doctors and human rights groups said in interviews that summary executions with machetes were being carried out in other slums around Port-au-Prince.

"We have reports of executions that are supposedly performed by the Haitian police," said Mr. Valdes, who added that an inquiry is under way.

Mr. Joseph, the Lavalas leader in Cité Soleil, said his community needs help, not bullets. "What we don't understand," he said, "is why those of us who are living here, who don't have money to send our children to school, who don't have money to eat, who can't sleep who don't have anything at all - why is it that the international community doesn't come here to help us?"

Little money has reached Cité Soleil, international observers say, because of the violence there and the desperate need for aid programs elsewhere in Haiti.

Mr. Valdes, the United Nations official in Haiti, said the international community must respond to concerns like those of Mr. Joseph. "Force is not a solution for the security problems in Haiti," he said. "You have to provide water, food, support in health, in education. We have not been able to do that."

Only last month, he said, did the United Nations in Haiti get money to begin providing some of that assistance in Cité Soleil.

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, International, of Monday, August 29, 2005.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |