| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| More Books and Arts |

| Posted December 9, 2007 |

| THE NATION |

| A Hail of Bullets, a Heap of Uncertainty |

By AL BAKER |

AFTER almost every high-profile fatal shooting by the police, a flurry of questions follows hard on the hail of bullets. Premier among them is, Did they have to kill him?

This often implies a more subtle subtext that goes to the heart of police training: Is there a middle ground? And is it possible to shoot to wound?

The answer, law enforcement officials and experts agree, is no, but not because the only alternative is shooting to kill.

|

While popular culture has embedded both extremes — the hardened mantra of “shoot to kill” and the benevolent private eye (think Barnaby Jones) who expertly inflicts only a flesh wound — the truth is that neither practice is a staple of police guidelines. In fact, the most likely result when a policeman discharges a gun is that he or she will miss the target completely. So an officer could no sooner shoot to wound than shoot to kill with any rate of success. In life-or-death situations that play out in lightning speed — such precision marksmanship is unrealistic.

In New York, many other municipalities and some federal agencies, guidelines instruct officers to shoot to “stop” — and in particular, to stop an assailant who poses a deadly threat to the officers involved or civilians.

“We do not train our agents to shoot to wound or to shoot the gun out of someone’s hand, we train them to shoot to stop the threat,” said William G. McMahon, the special agent in charge who heads the New York field division of the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. “In the milliseconds a law enforcement officer has to react during a life-threatening situation, aiming to wound is not an option.”

Agent McMahon faced tough questions a few weeks ago when a federal officer in the Bronx shot a suspect in the head, after the suspect had brandished a hand grenade and sped away in a car, dragging the agent 20 feet. That followed two fatal police shootings in Brooklyn, one in which the victim pulled out a hair brush that the police said looked like a gun, and another in which the victim wielded a broken bottle in his hand. Both shootings raised questions about the use of deadly force.

|

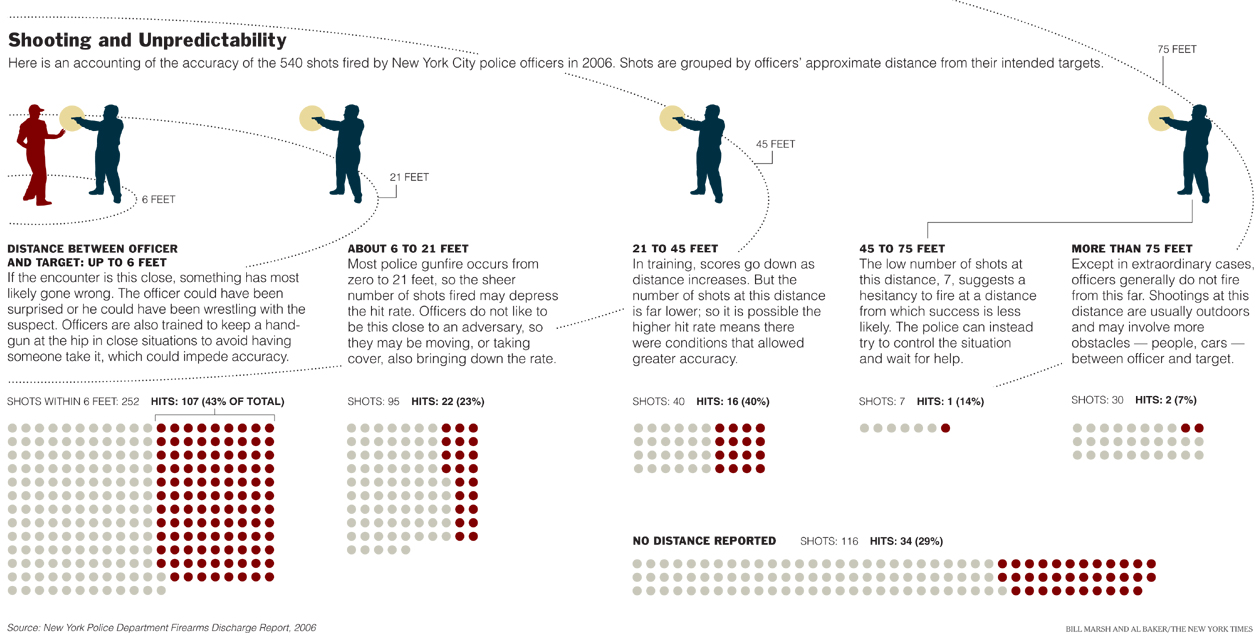

New York City police statistics show that simply hitting a target, let alone hitting it in a specific spot, is a difficult challenge.

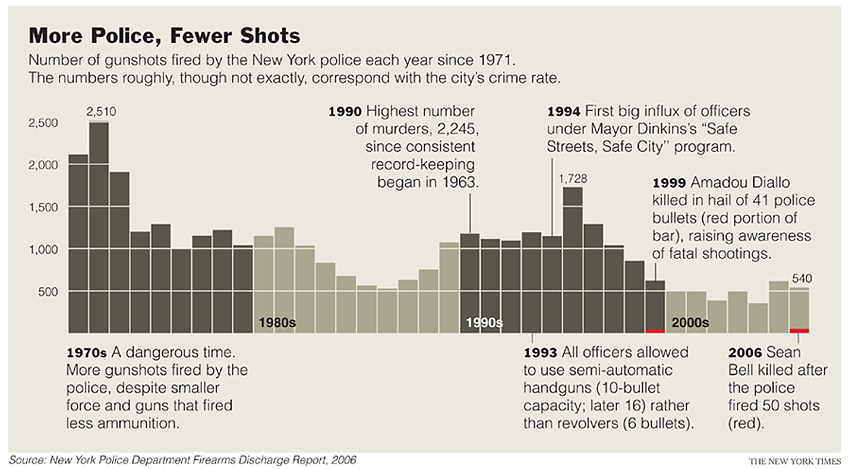

In 2006, in cases where police officers intentionally fired a gun at a person, they discharged 364 bullets and hit their target 103 times, for a hit rate of 28.3 percent, according to the department’s Firearms Discharge Report. The police shot and killed 13 people last year. In 2005, officers fired 472 times in the same circumstances, hitting their mark 82 times, for a 17.4 percent hit rate. They shot and killed nine people that year.

In all shootings — including those against people, animals and in suicides and other situations — New York City officers achieved a 34 percent accuracy rate (182 out of 540), and a 43 percent accuracy rate when the target ranged from zero to six feet away. Nearly half the shots they fired last year were within that distance.

In Los Angeles, where there are far fewer shots discharged, the police fired 67 times in 2006 and had 27 hits, a 40 percent hit rate, which, while better than New York’s, still shows that they miss targets more often they hit them.

Bad marksmanship? Police officials and law enforcement experts say no, contending that the number of misses underscores the tense and unpredictable nature of these situations. For example, a 43 percent hit rate for shots fired from zero to six feet might seem low, but at that range it is very likely that something has already gone wrong: perhaps an officer got surprised, or had no cover, or was wrestling with the suspect.

“When you factor in all of the other elements that are involved in shooting at an adversary, that’s a high hit rate,” said Raymond W. Kelly, the New York police commissioner. “The adrenaline flow, the movement of the target, the movement of the shooter, the officer, the lighting conditions, the weather ... I think it is a high rate when you consider all of the variables.”

John C. Cerar, a retired commander of the New York Police Department’s firearms training section, was more tempered in his assesment of the hit rates. “They’re acceptable,” he said. “In pristine conditions, you are going to get better hit ratios.” He said handguns were an imperfect weapon. “As long as the handgun is the main tool for the police officers to use, you are going to have misses,’’ he said.

Citizen’s rights advocates insist the statistics point up the need to train officers to recognize and employ other, less deadly options. “The low hit rate provides another reason why they should do everything possible to avoid having to shoot in the first place, given the likelihood they are going to hit something or someone other than their intended target,” said Christopher Dunn, the associate legal director of the New York Civil Liberties Union.

Mr. Kelly pointed to examples of excellent marksmanship, including a 2003 incident in which a City Council member was killed at City Hall. An officer fired six times at the assailant from about 45 feet away; four or five of the shots hit the gunman and killed him.

Interviews with police officials in Boston, Chicago and Los Angeles show that when the police do shoot, they are trained to aim at “center mass.” That gives the officer a margin of error, because missing the target can mean hitting bystanders. In stressful confrontations, experts said, the goal was to have the officer fall back on his training to aim for the center.

“You want instinct to take over,” one federal agent said.

New York police officials say that their policy manual includes several directives instructing officers to use the minimum amount of force necessary. For instance, the guide bans warning shots in deadly physical force situations — because police don’t use bullets as deterrents, and because errant shots can be dangerous. They also cannot shoot at a moving vehicle unless a deadly threat is coming from something other than the vehicle, like a gunman.

New York officials say they believe their officers use more restraint than the police in other major cities do. The police reports on gunfire do not include a breakdown of the victims’ race, which is often an inflammatory aspect of New York police shootings.

Mr. Dunn said the policies in the manual are “pretty good” in spelling out abstract rules on deadly force but added: “I am struck at the lack of practical direction about how to minimize the circumstances in which deadly force can be used.”

Candace McCoy, a professor of criminal justice at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, said that officers must be intimately familiar with the neighborhoods they patrol, and understand its natural perimeters, so they can intelligently contain an incident and defuse it short of using deadly force. They can find an in-between tactic, experts said, such as using a Taser, a baton or pepper spray.

But too often, Professor McCoy said, such middle ground for officers disappears. Once it does, and bullets start to fly, there is no telling where they will land.

“You take Olympic shooters, and they practice all the time, and they can hit a fly off a cow’s nose from 100 yards,” said Mr. Cerar, the retired commander. “But if you put a gun in that cow’s hand, you will get a different reaction from the Olympic shooter.” « Previous

Copyright 2007 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Week in Review, of Sunday, December 9, 2007.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |