| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| More Books and Arts |

| Posted December 2, 2007 |

| I.Q. Debate Adds A Chapter Online |

|

|

|

||||

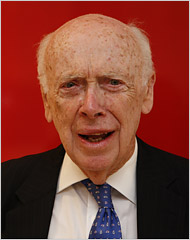

| JONATHAM PLAYER FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES | TONY CENICOLA/THE NEW YORK TIMES | OZIER MUHAMMAD/THE NEW NEW YORK TIMES | ||||

| Dr. James D. Watson | Charles Murray | Jacob Weisberg |

By PATRICIA COHEN |

Ever since the Nobel prize winner James D. Watson asserted six weeks ago that Africans have innately lower intelligence, fervid debates about race, genes and I.Q. have sprung up on the Web, in publications and in conference rooms.

But in recent days, along with long-simmering arguments over evidence, have come others about whether the topic is even worth studying, or whether it can be discussed openly without spurring charges of racism.

“It’s a subject that almost dare not speak its name,” said Howard Husock of the Manhattan Institute, a conservative research group, as he introduced a debate Wednesday night between James R. Flynn, the author of a new book “What Is Intelligence?” (Cambridge University Press), and Charles Murray, a co-author of “The Bell Curve,” the controversial 1994 book about intelligence that set off a previous free-for-all on race, genes and I.Q.

____________ |

|

| A slate series stokes arguments on race and intelligence. | |

____________ |

The risk of giving ammunition to racists or undercutting principles of equality hovers over such conversations like an uninvited dinner guest. That unwelcome visitor has been loitering at the online magazine Slate since last week, when it ran a three-part series arguing that hard science is showing that blacks’ I.Q. scores are lower than those of whites — and whites’ scores are lower than those of Asians — because of genetically based differences in intelligence.

Appearing on a site with a liberal bent and written by its generally liberal science and technology columnist, William Saletan, the articles drew particular attention — and particular scorn. “William Saletan and the Editors of Slate Demonstrate That They Are Not Members of the Genetic Elite” was the headline on the Web site of the economist Brad DeLong (delong.typepad.com). On his popular political Web site, talkingpointsmemo.com, Joshua Micah Marshall referred to it as “Will Saletan’s nauseating foray into black genetic ‘pseudo-science.’”

Mr. Flynn and Richard Nisbett, two noted researchers on intelligence, also criticized the Slate series as grossly one-sided. Mr. Flynn said he was most persuaded by evidence that the environment causes I.Q. differences, but added that certainty on either side is misplaced given that the research is still in its infancy.

On Wednesday, Mr. Saletan posted a fourth article labeled “Regrets,” confessing that he had not realized that J. Philippe Rushton, a researcher on whom he had heavily relied, is the president of an organization that has financed a segregationist group. He also amended his previous position, stating that it was too early to come to any firm conclusions about the causes of racial differences in intelligence.

“If I had to do it again, I would have been much more circumspect about judging” the evidence, Mr. Saletan said in an interview. He later added that he should have written about inequality and left race completely out of it.

Jacob Weisberg, the editor of Slate, said that since Mr. Saletan is a senior writer, his posts went up without anyone there reading them. “Given the sensitivity of the subject, Will’s commentary should have been carefully edited in advance of publication, and it wasn’t,” he wrote in an e-mail message.

Mr. Weisberg said he was disturbed by the casual “what if” thought experiment and some of the sources Mr. Saletan cited. “I wouldn’t have stopped Will from writing on this subject, but I would have challenged him on these and other issues,” he wrote. He added that a rejoinder by another Slate writer, Stephen Metcalf, was scheduled to be posted Monday.

Mr. Saletan said he was completely unprepared for the voluminous and vehement reaction. “I did not mean to start a wildfire.”

A subject as sensitive and complicated as this deserves to have a higher level of proof, he said, adding that he erred in treating it like any other topic.

“I don’t agree that it’s best not to discuss it,” he said, but “you have to do it in a responsible way and always with a constructive purpose.” Judging from his own experience, he said, the Internet is not a place where that can be done at the moment.

“I’m a little disappointed in myself,” he added.

____________ |

|

| Civil or not, the Web joins the fray over a sensitive subject that may never be settled. | |

____________ |

Linda S. Gottfredson, a sociologist at the University of Delaware, insists that Mr. Saletan has nothing to apologize for. Ms. Gottfredson, who along with Mr. Flynn had been participating in a separate monthlong online debate about intelligence sponsored by the libertarian Cato Institute, wrote that Mr. Saletan “may be the first journalist to so directly acknowledge the scientific evidence” supporting a genetic explanation for racial differences in I.Q. “and to be allowed to publish his views.”

She calls the fierce response generated by the Slate articles evidence of “moral panic.” Ever since the 1970s, Ms. Gottfredson said in an interview, most researchers have steered clear of the subject altogether (Mr. Murray aside). “No one wants to stick their neck out and say what they really think for fear that they’ll get shot down like Watson or criticized,” she said. “People are in hiding.”

Amid the controversy over his comments last month, Dr. Watson, 79, apologized for his remarks and resigned as chancellor of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory on Long Island.

Ms. Gottfredson says the cause of the black-white achievement gap is one of the most pressing social science questions, and the refusal to consider genetic causes means either blaming white racism or black culture, making it someone’s fault and placing the issue “in the moral realm.”

“We’re ginning up more tensions by denying it,” she contended.

To Eric Turkheimer, a psychology professor at the University of Virginia who specializes in behavior genetics, the research itself is morally weighted. Given the complex interaction between genes and the environment, Mr. Turkheimer said, “the question is fundamentally impossible to settle scientifically because we can never take people out of their environment.”

That doesn’t mean research into genetic differences in intelligence should be banned, he said, but it should be judged. “What troubled me about posts at Cato” — an exchange Mr. Turkheimer participated in — “and the tone of Saletan’s blog is the assumption that because these papers are labeled as science, they are value-neutral and they’re as deserving of respect as any other scientific hypothesis,” he said of genetic racial theories.

“But you can’t get away from what these people are trying to prove, which is exactly the basis of the stereotypical beliefs that informed segregation here for 200 years.”

If the Internet, as Mr. Saletan says, is not the place for civil discourse about race and I.Q., the Harvard Club clearly is. That is where the Manhattan Institute held its debate this week. “Not one single person has run out of the room screaming,” Mr. Murray said at the evening’s end to the 70 or so guests, a handful of them black. This issue has “festered in the American psyche,” he added. “Everybody pretends it doesn’t exist.”

Mr. Flynn, who said he had been attacked by both conservatives (for playing down the significance of genes) and by liberals (for arguing that black culture is at the root of the I.Q. gap), told the group, “I want to say how deeply I believe in this sort of discussion.” He later explained that his own desire to disprove the genetic arguments is what spurred his research.

“If at any time we had cut off scientific examination of race in the past,” he said, “we would have more racial prejudice than we do now.”

Copyright 2007 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, The Arts, of Saturday, December 1, 2007.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |