| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| More Books and Arts |

| Posted July 2, 2007 |

| ROMAN CANDLES | |

|

|

Michael Beirut |

|

| 2,000 Years Later, Wrapped in the Star-Spangled Toga |

By ADAM GOODHEART |

THIS Fourth of July, millions of ordinary citizens across the land are planning to celebrate our nation’s birthday with that most distinctively American tradition: the backyard toga party.

Well, O.K., not really. But the idea might not be so farfetched. Recently, it has seemed that ancient Rome is everywhere — and especially comparisons of modern America to the ancient empire. Moreover, it is one of the few things on which all segments of the political spectrum — left and right, Christian fundamentalists and Islamic radicals, Ivy League professors and renegade bloggers — seem to agree.

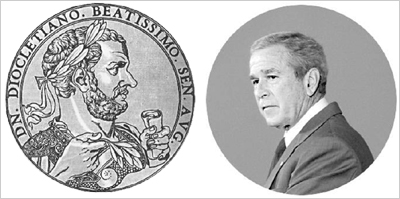

Most recently, a book by Cullen Murphy, titled, plainly enough, “Are We Rome?” begins with an extended comparison of President Bush to the emperor Diocletian from the third century A.D. Everything from their respective foreign policies to their retinues of courtiers comes under scrutiny. (It’s a bit of puckish humor that the author, whose sympathies are decidedly of the liberal sort, chooses that particular Roman ruler, who was famous for feeding Christians to the lions.)

Mr. Murphy, especially, draws parallels between Rome’s imperial predicament and what he sees as ours: the problems of a vast, multiethnic nation with a messianic view of itself and an often simplistic view of the rest of the world, stretched too thin beyond its borders and facing mounting challenges within them.

| Rome was the founders' model of a thriving republic. Now it represents an empire in decline. |

He finds echoes of the emperors’ reliance on legions of Visigothic mercenaries in the country’s outsourcing of security contracts to Halliburton and Wackenhut.

He describes corrupt imperial bureaucrats as the moral forebears of K Street lobbyists:

“I don’t know how it would be phrased in Latin, but one of Jack Abramoff’s e-mails (‘Da man! You iz da man! Do you hear me?! You da man!! How much $$ coming tomorrow? Did we get some more $$ in?’) captures the spirit of public service in the late empire.”

Meanwhile, other commentators have their own comparisons. Conservative bloggers thunder about illegal Mexican immigrants as latter-day versions of the Vandals and Ostrogoths. Fundamentalist pastors like Pat Robertson warn of Neronian moral decay — pornography, abortion, gay marriage — that, they say, is hollowing out our society from within. And it seems as if everyone who watched the HBO series “Rome” has a pet theory on which ancient warlord resembles which modern pol (Pompey as Al Gore, anyone?).

Even Middle Eastern jihadists have joined in. Last November, Abu Ayyub al-Masri, the leader of Al Qaeda in Mesopotamia, released an audiotape in which he vowed: “We will not rest from our jihad until we are under the olive trees of Rumieh and we have destroyed the dirty black house — which is called the White House.” The reference to “Rumieh” puzzled translators at first. It is Arabic for the Roman Empire.

What few remember is that America has always been compared to Rome. It’s only the nature of the comparisons that are constantly changing. Nearly a half-century ago, in the aftermath of the McCarthy era, Stanley Kubrick’s “Spartacus” was a thinly veiled attack on the Hollywood blacklist. In 1979, Tinto Brass’s notorious “Caligula” gave us ancient Rome as a Saturday night at Studio 54, with togas.

But it all started long before that, and the comparisons began as positive ones. America’s early leaders thought about Rome quite a lot, comparing themselves to statesmen whose names, unlike those of Nero and Caligula, are all but forgotten today: the noble freedom fighters like the Gracchus brothers, or the virtuous legislators like Cato the Younger. Their emphasis was usually not on the Roman Empire, but rather on the republic that preceded it.

| Rome is a handy metaphor for the McCarthy era, disco days and the dangers of Mesopotamia. |

In fact, George Washington’s favorite literary work was a play about Cato by the 18th-century English author Joseph Addison. So fond was he of Addison’s “Cato” that one of the first things he did at the end of the winter of 1778, when his men had scarcely recovered from the frozen misery of Valley Forge, was to arrange a performance by his troops. In the 19th century, an immense marble statue of Washington in the guise of a Roman god — naked except for some strategically placed drapery — actually stood in the rotunda of the United States Capitol. Thomas Jefferson, meanwhile, was painted in a Roman laurel crown by his friend and fellow Revolutionary hero Thaddeus Kosciuszko.

With few modern examples of successful republics to inspire America’s founders, ancient Rome provided an indispensable role model. Overlooked, however, is that the generation that fought the Revolution was not simply interested in creating a republic. From the beginning, many American patriots were out to build an empire. In the summer of 1776, an edition of Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense” referred to “the rising empire of America” on its title page.

In the same year, William Henry Drayton of South Carolina gave a speech in which he recalled that the once-mighty Roman Empire, which had lasted a millennium, had been supplanted by the British Empire — which, in his estimation, had lasted a mere decade or so. Now, he continued, “the Almighty ... has made choice of the present generation to erect the American Empire.”

The question was: could America’s republican aspirations flourish in harmony with its imperial ambitions? The two were not necessarily wholly incompatible. After all, Rome’s dominions had spanned the Mediterranean even while it was still ruled by a senate. And the United States did not need to look overseas for territories to conquer: an entire continent stretched westward.

So the founders decided they could have it both ways. Benjamin Franklin himself, during the Constitutional Convention of 1787, would refer to the nation he was helping create as both a “republic” and an “empire.” Franklin’s strongest endorsement of America’s God-given imperial destiny appears today on many conservative Web sites: “And if a sparrow cannot fall to the ground without His notice, is it probable that an empire can rise without His aid?” As Mr. Murphy notes, that quotation also appeared on Dick and Lynne Cheney’s 2003 Christmas card.

Franklin and his contemporaries were all too aware, however, that in setting up their nation as a latter-day Rome, they were also all but ensuring centuries of paranoia to come about whether America was destined to go the way of its imperial predecessor. The eventful year 1776, after all, had seen the appearance not just of the new United States but of the first volume of Edward Gibbon’s “Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.”

|

Hulton Archive/Getty Images; left, Saul Loeb/Agence France-Presse - Getty Images |

| Flip Sides President Diocletian and Emperor Bush? No, but Roman parallels are a perennial temptation. |

Indeed, the fretting began almost immediately. In the early 19th century, one Maryland politician, lamenting his countrymen’s increasing love of “public shows and spectacles,” warned: “History records that the declining days of the Roman republic, upon which the throne of the Caesars was erected, was attended by banquets and revels, and marked by the exhibition of rhetoricians and gladiators.” The occasion of debauchery and depravity that inspired this outburst was, naturally, the 1817 inauguration of President James Monroe.

There’s one warning sign from ancient Rome’s history, though, that everybody, past and present, seems to have ignored. The juggernaut of Roman conquest stalled in only two places. One, of course, was along the Rhine, where warlike German tribes held the course of empire in check. The other place was the valley of the Tigris and Euphrates, or ancient Mesopotamia — roughly, modern Iraq.

For centuries, one would-be conqueror after another marched his legions into the east, only to return in disgrace, or not at all. A few decades before Diocletian, there lived a Roman emperor named Valerian, a man from a fine old senatorial family. His army was annihilated not far east of the Euphrates.

Valerian was taken as a captive back to the enemy capital, where the Persian king, according to one ancient historian, amused himself by using the Roman emperor as a footstool for mounting his horse. When the erstwhile master of the known world finally died, his skin was stuffed with straw as a trophy.

Adam Goodheart is director of Washington College’s C. V. Starr Center for the Study of the American Experience.

Copyright 2007 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Week in Review, of Sunday, July 2, 2007.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |